Keith Wade, Schroders’ chief economist and strategist, who joined the company in September 1988, conducts a comprehensive analysis of the noteworthy trend of declining inflation and interest rates, exploring its crucial implications for markets, examining China’s impact on globalisation, and anticipating how these themes provide insights into the evolving risks for investors.

In looking back over my career at Schroders, I wanted to focus on three themes that played a major role in driving economies and markets over the past 35 years. The first is a big theme that ran through the entire period and may now have come to an end, the second is one that started as an economic trend but has become more geo-political and the third is an old theme, one that has challenged economies for decades.

These three themes are the great disinflation, the rise of China, and the rise and rise of government debt. There are other trends, but these three have been the most important in my view and have often been at the root of the crises we have experienced over the period. How they play out will be key to the outlook for the next 35 years.

The great disinflation

In 1988, when I started as a UK economist at Schroders, the inflation rate in the UK had just risen above 6%, the highest for six years, and interest rates were high and rising. The economic debate was on how inflation had managed to come back after the deep recession of the early 1980s when three million people became unemployed. The market debate was on how far monetary policy would have to be tightened to tame inflation.

Today, the Bank of England (BoE) and central banks around the world along with the markets are asking the same question as they endeavour to bring inflation back down to target amidst another cost-of-living crisis.

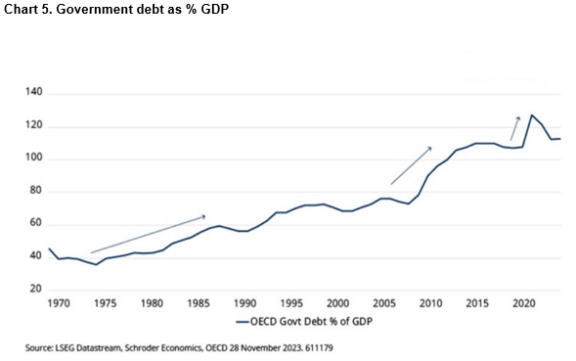

Yet, despite book-ending my career at Schroders, accelerating inflation has not been the theme of the past 35 years. Instead, the period can be characterised as the great disinflation where inflation has steadily fallen year after year (see chart 1). This culminated in a period after the global financial crisis of 2007-08 (the GFC) when the concern shifted from disinflation to outright deflation with central banks ultimately printing money and embarking on quantitative easing. Economists asked if the world economy was about to follow the Japanese experience of falling prices.

Falling inflation helped drive returns, but also bouts of “irrational exuberance”.

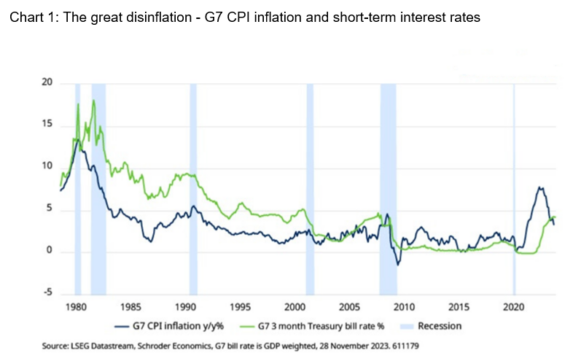

The big trend of falling inflation and interest rates had important consequences for markets and brought significant returns from both equity and bond markets.

Until 2021, government bonds had matched equity returns, but putting aside the question of whether we are moving to a new more inflationary regime, it is clear that those stellar return figures flatter to deceive. As can be seen from chart 2, market returns have been volatile and were punctuated by a series of bull and bear markets.

Many of these fluctuations were a consequence of the fall in inflation itself which released liquidity into real assets, primarily equity and property, as interest rates fell, and investors shifted from the safety of cash. This drove asset values higher, fuelling the bull market. However, the liquidity also flowed for longer and to places where it probably should not have gone.

Rising markets can develop a momentum of their own as they draw in capital from investors fearful of missing out. The incentive to keep up with the competition and participate is intense and, as a result, market prices can continue to travel beyond what might be justified by the fundamentals.

Some economists point this out at the time, but more often than not are run over by the herd chasing the bull market.

As John Maynard Keynes noted back in the 1930s: “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can remain solvent”.

Underlying this is the difficulty of knowing when markets have gone too far, as former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan said: “Clearly sustained low inflation implies less uncertainty about the future, and lower risk premiums imply higher prices of stocks and other earning assets… But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions…”

History went on to prove his point. Greenspan made those remarks in 1996 just as dot-com stocks were getting going and although there was already talk of a bubble, the bull market ran on until March 2000.

An unforeseen consequence of the great disinflation was a series of investment bubbles where markets became detached from fundamentals. These often proved to be the best and worst of times to be an economist: the best due to the surge in interest and media attention, and the worst because the economics became irrelevant to the market.

More importantly, alongside financial losses, the bursting of those bubbles always had significant economic consequences.

The end of the subprime mortgage bubble in 2007 led to the collapse of the global banking system and the Great Recession – the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

East Asia suffered a similar fate following the 1997 crisis, particularly after the IMF rescue plan imposed austerity on the region. The euro was another victim as the unwind of capital flows post-GFC led to the crisis of 2012 with the Greek economy experiencing massive losses of jobs and output.

One factor that helped drive theme one is the emergence of China as an economic power.

The rise of China

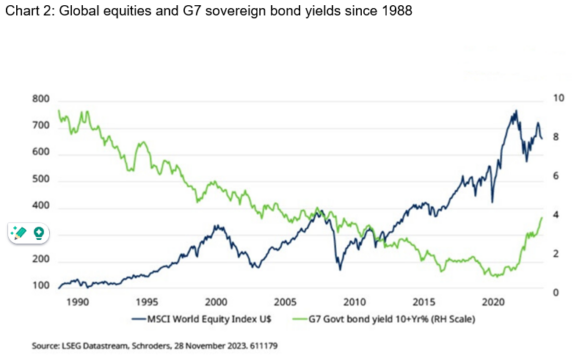

The emergence of China as a significant economic player over the past 30 years has certainly shaken the world economy. If there was one chart that captures this, it would be chart 3 which shows the increase in China’s share of global trade.

Starting at 1% in 1982, this has now risen to 12% and was briefly higher in 2021 at the height of the lockdown-related boom in stay-at-home goods trade. The acceleration really began after China’s ascension to the World Trade Organisation at the end of 2001 which opened up access to international markets.

Today, China has the highest share of any country in global trade. The chart also shows the corresponding decline in trade share of the US, Germany, and the UK. The arrival of China has had consequences not just for international trade and investment but also for inflation, growth, inequality, and politics in the rest of the world.

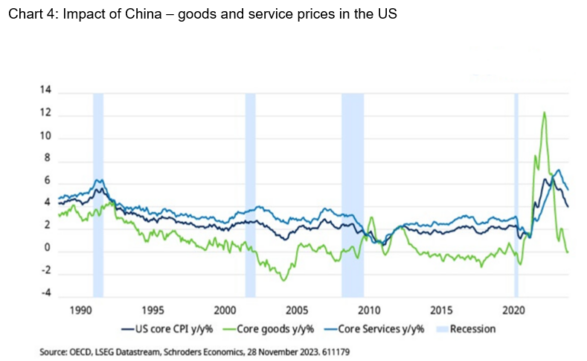

The opening up of China was a positive supply shock for the world economy, increasing the supply of goods and labour. The effect was to help contain global inflation by weighing on prices and wages and contributing to the fall in inflation. This could be seen most clearly in the West with the decline in goods price inflation which turned to deflation during most of the decade before the pandemic.

Chart 4 shows the picture for the US whereby the softness in goods prices helped offset more rapidly rising service sector prices and enable inflation to stay close to its 2% target. Note how the recent re-opening of supply chains after the pandemic has brought goods price inflation back down and contributed to the fall in inflation in 2023. The same pattern can be seen in CPI indices in the UK and eurozone.

As a consequence, for much of the period, the rise of China was seen as a positive economic benefit. Alongside lower inflation, multi-nationals invested in China, their supply chains grew exponentially and by reducing the costs of production this directly contributed to the rise in the profit share on income. Meanwhile, consumers benefitted from the supply of cheaper goods.

However, it has also become clear that the counterpart to higher profits – the squeeze on labour income in the West – has become a source of discontent with the economy which has spilled over into political unrest. Those declines in trade share shown in chart 3 reflected the hollowing out of industry in the OECD economies with the loss of many well-paid manufacturing jobs.

There is considerable debate as to how much of this should be attributed to the rise of China and globalisation. For example, new technologies have played a role. Nonetheless, as with the fall in inflation and boom in asset prices it has tended to exacerbate inequality in the West. Populists have seized on the opportunity to exploit this discontent with a mix of nationalism and protectionism.

The change in attitudes toward China may, however, have been when business in the West realised that China was evolving from being a supplier to a competitor. Chinese firms were beginning to compete head on with their OECD counterparts. This was, of course, inevitable: as a country increases its living standards it will look to move its production towards the higher value-added end of the range.

Nonetheless, by the middle of the last decade, China had overtaken the US as the economy with the largest trade share (see chart 3). This also coincided with the publication in 2015 of Made in China 2025 by the Chinese government – a 10-year plan to update China’s manufacturing base by focusing on 10 key hi-tech sectors. The report crystalised fears that China would take market share from Western companies and acted as a catalyst for a protectionist response.

Today, the need to stymie Made in China 2025 is one of the few issues that has bi-partisan support in the US Congress. The move toward increasing tariffs and restricting trade in technology has been given added impetus by the security threat from China that many in the US and Europe now perceive. The situation has not been helped by China’s support for Russia in Ukraine which has opened a fault line with the West, although in practice this may prove to be a moderating factor on the Russian leadership.

Going forward, many see geo-political tension as a threat to globalisation and a potential reversal of the disinflationary trend in goods prices which has helped contain inflation. In Schroders’ view, this remains to be seen as firms have tended to react and re-configure supply chains to other countries rather than cut them altogether.

Even on the US-China axis there are questions as to whether the US and China can successfully ringfence security-sensitive areas of activity whilst otherwise continuing to trade and invest as usual. The recent meeting on 15 November last year between Presidents Biden and Xi suggests there is still considerable mutual interest between the two superpowers.

We may not get back to the deflation in goods prices seen in the last decade, but China has a strong interest in maintaining and increasing export volumes against a backdrop of weakness in its domestic economy as a result of the downturn in the property sector. Prices will stay competitive as a result.The rise and rise of government debt

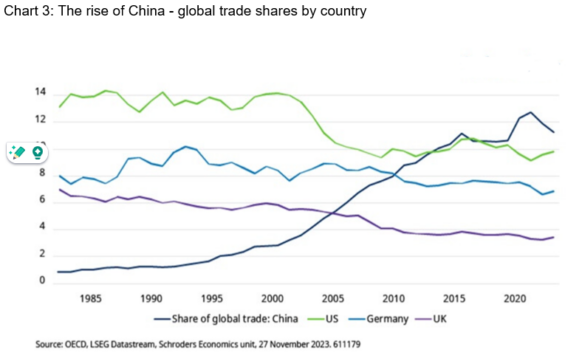

The third trend is one that like inflation was seen as a problem 35 years ago and is becoming one once again: the inexorable rise in government debt which is currently running at 113% of GDP for the OECD. Figures from the IMF show that both the US and UK now have a government debt to GDP ratio of more than 100%.

Back in 1988, debt across the OECD had risen to 60% of GDP and although nearly half today’s figure the concern was that this was a rise of 50% over the past 10 years. Since 1988, there have been two significant jumps in debt, the first as a result of the GFC and the second due to the cost of the pandemic (see chart 5).

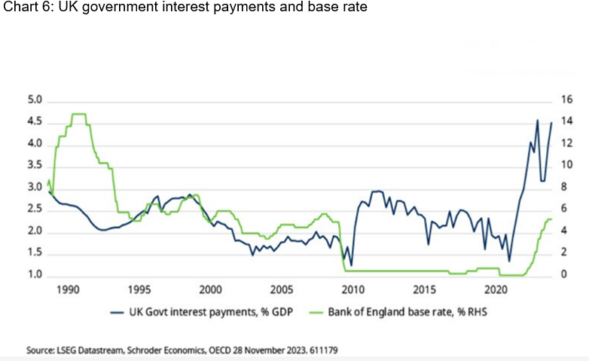

Like inflation, however, the level of OECD government debt was not a major problem for markets over the past 30 years. This was another consequence of the great disinflation and the fall in interest rates over the period. The cost of public sector borrowing fell, enabling governments to sustain higher debt levels. For countries such as the UK the pandemic period initially saw government interest payments as a share of GDP fall significantly as short rates were cut to almost zero and QE restarted.

However, that changed as interest rates rose and the true cost of the increase in government debt was felt. For the UK, the high proportion of inflation-linked bonds, over one-fifth of outstanding government debt, was also a factor in taking UK interest payments to 4.5% of GDP in Q4 2022, the highest since the end of World War II.

Schroders expects inflation to improve and for interest rates to decline in 2024 in the US, eurozone, UK and across the OECD (with the exception of Japan). However, government debt will remain in the spotlight as (a) the decline in interest rates will not take rates back to pre-pandemic levels with equilibrium in the US and UK thought to be around 3.5% for example, and (b) funding budget deficits will require a significant increase in purchases by the private sector and quasi-public institutions such as Sovereign Wealth Funds.

This reflects the high level of current government borrowing at a time when the economy is operating above its normal capacity. Going forward, unemployment will rise further as part of the inflation reduction process, increasing government expenditure and reducing tax revenue. In other words, structural deficits have risen significantly.

Furthermore, central banks are set to continue to reverse quantitative easing. The BoE says it will reduce its holdings of UK government bonds by £100 billion next year and, when combined with expected government borrowing, we can expect supply of some £200 billion of gilts in 2024 (8% GDP). Clearly funding risks will rise especially as a UK general election will need to be held before December 2024. The UK is not alone as the US faces similar arithmetic and a Presidential election in 2024. Both countries also run current account deficits and so rely on overseas buyers (“the kindness of strangers” as former BoE governor Mark Carney put it). However, unlike the UK, the US enjoys the exorbitant privilege of having the world’s reserve currency which helps create natural demand for the US dollar.

The combination of higher interest rates and structural deficits means investors will increasingly question the sustainability of the rise and rise in government debt. Clearly, such an outlook implies challenging times for governments who remain committed to spending increases and are reluctant to increase taxes.

Some conclusions and implications for the future

These three trends have shaped the economic and market environment of the past 35 years. They are not the only factors – the impact of technology and climate change have also played a role but in my view have been the most important over this period. Looking ahead, they provide a perspective on how the risks faced by investors will evolve.

The long tailwind from the great disinflation is clearly fading and we are moving to a world where inflation will have adverse as well as positive effects on markets. The implication is that real assets such as equities and bonds will have to rely more on growth in earnings and rents for returns than revaluation effects. Do not expect rates to return to the levels seen between the aftermath of the GFC and the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the negative correlation between equity and bond returns, which has been so helpful for multi-asset portfolios, is already unwinding as bond yields will be more driven by changing inflation rather than growth expectations. That could make traditional balanced equity-bond portfolios more volatile.

If liquidity is tighter then capital should be allocated more carefully as the hurdle rate on investment is higher. Some argue this will mean more financial market stability and fewer bubbles. I doubt this will happen as greed and fear will continue to drive markets and we have had bubbles at higher interest rates than today.

Where I do see a change is in the nature of risk. Inflation and interest rates will always be important, but looking ahead we are set for more political risk. On the geo-political side, the world has to learn to live with the continuing advance of China and how to manage greater economic competition with the OECD countries. Expect more tensions between the US, China, and Europe.

On the domestic side, the deterioration in government balance sheets means that stress will continue to rise between the aims of politicians and economic realities. The next crisis could well be a sovereign debt crisis in an OECD economy.

This does not make me gloomy about markets. There have been many improvements in the world economy over the past 35 years and there are tremendous opportunities and new themes to exploit. Nonetheless, it pays to know where the next set of risks are coming from.