The most far-reaching change in the South African retirement landscape in many years took effect yesterday.

In a nutshell, the two-pot system, as the name suggests, will entail future retirement savings being allocated to two pots – called components in the legislation.

One-third will go to a savings component, which retirement fund members access and two-thirds to a retirement component. Members will be able to withdraw from their savings component at any time, but only once a tax year. The retirement component must remain invested until retirement.

The compulsory preservation component (the retirement component) will end the widespread practice of people cashing in their retirement savings whenever they change jobs. In fact, many people change jobs just to access their retirement funds. This “leakage” not only leaves individuals without sufficient retirement capital when they reach old age, but also means the overall pool of South African retirement assets is smaller than it should be.

Impact on the fiscus and the economy

Estimates from the government and various financial institutions suggest that somewhere between R50 billion and R100 billion will be withdrawn in the first month or two after the two-pot system takes effect. This will largely be a one-off event, because future withdrawals will be based on one-third of new contributions from September onwards and will therefore be spread out over time.

This will have three immediate implications.

First, the government’s coffers will swell because these withdrawals will be taxed. The 2024 Budget pencilled in an additional R5bn in tax revenue in because of two-pot withdrawals.

Second, consumers will have more money to spend. A portion of withdrawals will probably go towards settling debt, but the remainder will be spent because it is unlikely that people will withdraw savings only to save it again. Combined with lower inflation and coming rate cuts, the medium-term outlook for consumer spending has therefore improved.

Consumer inflation declined to 4.6% year-on-year in July from 5.1% in June. This is close to the midpoint of the South African Reserve Bank’s target range of 3% to 6% and seals the deal for rate cuts starting at the September meeting of the bank’s Monetary Policy Committee.

Will withdrawals hit financial markets?

Third, there will be some selling of investments to realise the cash payouts. Could it have a disruptive impact on local financial markets? Probably not.

The withdrawals will most likely be staggered over a few weeks or even months because not all retirement fund administrators will be able to handle the expected volume of requests at the same pace. A directive from the South African Revenue Service also needs to be issued in each instance, which might delay payouts somewhat.

Moreover, retirement funds already hold cash that will act as a first buffer as the withdrawal requests come in. According to the Alexander Forbes Large Manager Watch, cash holdings in the country’s largest balanced funds – a proxy for the broader retirement industry – were at 2.7% at the end of June. This is a relatively low percentage by historic standards, but if applied to the R4 trillion-plus retirement industry, should be enough to cover expected withdrawals.

Most importantly, however, is that the JSE is a large and liquid equity market with an average daily equity turnover of about R20bn. The average daily turnover on the local bond market is several times larger. As for global markets, these will not even notice if there is large selling by South Africans.

At any rate, market participants do not seem spooked by the prospect of two-pot withdrawals, because the FTSE/JSE All Share Index hit a new record close above 84 000 during the week. Investors are increasingly optimistic that a US soft landing will materialise, and that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates next month, with the SARB not far behind. There is also growing optimism that South Africa is entering a phase of faster economic growth (from a very low base) and less political noise (also from a low base).

Link between savings and fixed investment

Most of the media attention on the new retirement system has been on the ability to access the savings component, and probably correctly so, because there is much financial education work to be done.

But the more important impact over time will come from compulsory preservation. At an individual level, people should end up with substantially higher retirement benefits all else being equal. Modelling by Old Mutual actuaries suggests that the average retirement benefit of retirement fund members could rise from the current two to three times of final salary to up to nine times of final salary, even with the full savings component being accessed.

The government has proposed the introduction of auto-enrolment so that all formally employed individuals have some form of retirement savings, but it does not form part of the two-pot system, and no timelines have been presented.

At a macro level, compulsory preservation (and auto-enrolment, if it is implemented) can contribute to raising South Africa’s low savings rate.

It is ironic that South Africa has an extremely sophisticated financial system, including retirement funds, asset managers, and life insurers, yet the country does not save enough. Partly, it is a victim of its own success: the sophisticated financial system also facilitates borrowing, which is basically negative saving.

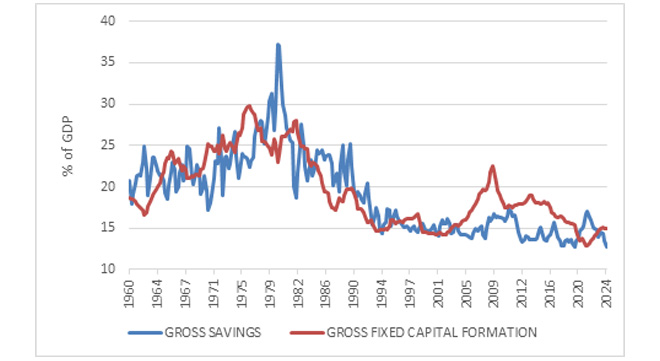

As the chart below shows, there is a strong link between savings and fixed investment. A low savings rate implies a low investment rate unless foreign savings can be imported by running a current account deficit. This is fine under normal conditions but has the major drawback that these foreign flows can be reversed, particularly if they are largely portfolio investments. This is the case in South Africa, where most foreign capital inflows head for the JSE to buy bonds or equities – “hot money” that can leave at the click of a button – instead of being invested in long-term businesses as “foreign direct investment”.

The chart shows a worrying decline in savings over time, partly because of increased borrowing and taxation levels, and partly because of rising unemployment. Investment rates have been depressingly low as a share of GDP over the past 30 years, apart from roughly between 2005 and 2015. However, as the chart shows, domestic savings were insufficient to fund this investment boom, and the country ran a large current account deficit during that time, which gained it membership of the Fragile Five club (Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey).

SA savings and fixed investment as a share of GDP

Source: SA Reserve Bank

Domestic savings is a more stable source of funding for fixed investment, and fixed investment is crucial for sustainable economic growth. If there is one thing on which economists agree it is that countries that enjoy long periods of rapid economic growth have high investment rates.

At 15% of GDP, South African investment levels are about half of where they should ideally be. The blame does not primarily lie with a lack of domestic savings, but with political and policy uncertainty, institutional bottlenecks, and depressed business confidence. But if investment spending was to pick up as some of these challenges are addressed, a shortfall of domestic savings means the current account will start widening again, exposing the country to sudden swings in capital flows. A growing retirement system can ease this constraint over time.

However, it will have to coincide with government borrowing declining relative to GDP. Government borrowing – dissaving – consumes a large portion of the domestic savings pool. This “crowds out” private borrowers and raises interest rates, particularly because the market has a dim view of the government’s creditworthiness. Despite the recent decline in government bond yields, they remain elevated.

Moreover, the large increase in government debt levels over the past 15 years has not been associated with productive spending, such as large-scale infrastructure upgrades that could facilitate future economic activity.

Demographic profile favours saving

Although the two-pot reforms took several years to come to fruition, the timing is right. South Africa has a young population that will be moving into its peak earning and contribution years over the next decade or two. Meanwhile, the share of older people who will draw down from the retirement system is small. More money in, less money out means a growing pool of savings.

The big challenge in South Africa is high unemployment, particularly youth unemployment. People cannot save for retirement if they don’t work. Nonetheless, South Africa has a better demographic profile than many richer countries in the Northern Hemisphere, with smaller cohorts of younger workers that must support an ever-growing number of retirees. No wonder that questions are being asked about the sustainability of these systems and the political implications of reforming them (such as raising retirement ages).

Reluctance to invest in infrastructure

A final point is that although a growing pool of retirement savings should benefit the domestic economy, the extent of the positive impact will depend on where the savings are allocated. For instance, retirement funds can allocate up to 45% to offshore assets under Regulation 28, and this does not contribute to local economic development directly. However, it does contribute to national wealth and provides a natural hedge against periods of rand weakness. Assuming the prudential limits under Regulation 28 do not change, the remaining 55% will flow into domestic markets.

Ideally, a portion of retirement savings would go specifically to infrastructure projects. Some politicians like the idea of “prescribed assets”, forcing retirement funds into a set of investments determined by the government, to achieve a specific policy outcome.

However, this is neither welcome nor necessary. It is unwelcome because it can lead to inferior investment outcomes. It is unnecessary because Regulation 28 already provides ample room for retirement funds to invest in infrastructure.

The biggest reason behind a lack of private investment in infrastructure to date has not been an unwillingness on the part of retirement funds but the lack of investable infrastructure projects. This is starting to change at an ideological and a practical level. Ideologically, the government has backed away from the view that the state must control the country’s network industries, and it now welcomes private sector participation (not to be confused with privatisation, however). Practically speaking, much more attention is being paid to the regulatory impediments.

Deputy Finance Minister David Masondo made a similar argument recently at a conference hosted by Old Mutual, noting that the government aims to “promote a policy environment that enhances pension portfolio returns, promotes market stability, and avoids compromising both the pre- and post-retirement lives of citizens”.

Mandatory preservation is the game-changer

Most of the attention on the new two-pot system has been around the early access to savings for emergencies. But it is the introduction of mandatory preservation that is the game-changer.

However, its success will ultimately depend on it being combined with other reforms, including fiscal consolidation, private sector participation in infrastructure, and deregulation, to raise economic growth and employment levels. It can then become a self-reinforcing positive spiral with a powerful impact on the domestic economy and local markets in the years ahead.

Izak Odendaal is Old Mutual Wealth’s chief investment strategist.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies.

I want to claim my provident fund

Want too withdraw money out of my savings pot

Where can i register?

You don’t have to register.

I want to withdraw