The story of South Africa’s modern economy cannot be told without Anglo American, the giant mining conglomerate that also owns De Beers. It was the Kimberly diamond rush in 1867 and Witwatersrand gold stampede in 1886 that pulled South Africa into the global economy and financial markets. The dark flipside of the rapid development and industrialisation was the exploitation of black workers from across southern Africa, planting the seeds of the apartheid system.

Anglo American’s name points to its origins and global links, started in South Africa in 1917 by a German Jewish immigrant, Ernst Oppenheimer, with funding from American and British investors and lenders.

It became a major mining conglomerate, but by the 1980s capital controls meant its profits were trapped domestically, and it ended up as a sprawling domestic business empire, owning everything from banks to wine farms. In the post-apartheid era, it returned to focusing purely on mining, listing in London to raise capital for its global ambitions. The fact that it is now widely seen as a takeover target or a candidate for restructuring suggests that this goal was achieved only with mixed success.

Without getting into the merits of BHP’s unsolicited bid for Anglo American, which the latter has rejected, or the many complexities associated with such a transaction, or speculating too much on Anglo’s future, there are at least three notable elements worth exploring:

- What does it tell us about the global mining cycle?

- What does it tell us about South Africa’s mining climate?

- What will it mean for the JSE if a stalwart share was to disappear?

Dr Copper

BHP is primarily interested in Anglo’s South American copper mines.

Copper remains the best metal for conducting electricity, and therefore has a major role to play in the electrification of energy supplies and the green transition. A battery-powered electric vehicle requires about three times more copper than a traditional internal combustion car, for instance.

Even if elements of the green transition end up lagging expectations – electric vehicle sales have recently lost momentum internationally, although production has been ramping up in China – the artificial intelligence boom will put great strain on electrical grids. As much as we think of AI as existing somewhere “in the cloud”, it a physical presence in data centres and needs consistent electricity supplies. All this will require copper. For instance, Microsoft recently announced a $10-billion deal with Brookfield to purchase 10GW electricity to power its data centres. That is enough electricity for 1.8 million homes.

Global copper production seems unlikely to keep pace with this demand, based on the mines that are operating today. Future mines might, but they still need to be developed, a complex process that takes a decade or more from start to finish. Regulatory hurdles are often a bigger challenge than the engineering ones. Indeed, the reason there are always big commodity cycles is because of the long lags between demand rising and supply responding. Often, by the time supply responds, demand has turned and prices slump.

Anglo learned this lesson the hard way. In 2008, at the peak of the commodity boom, it paid $5bn for Minas Rio, a Brazilian iron ore project under construction. When the mine finally started producing iron ore in 2014, market dynamics were very different and the iron ore price about 40% lower. The debt associated with this project (and others) posed an existential risk to Anglo in 2015 and before commodity prices turned somewhat.

Other miners experienced something similar, and the result has been a sector that has been very disciplined in terms of capex spending on new projects. Adjusted for inflation, capex spending by listed mining companies remains stuck at 2009 levels.

When commodity demand does decisively turn, supply shortages could be the order of the day. BHP’s bid is a powerful signal that the mining houses themselves are starting to position their businesses for such an outcome. Investors are starting to take note.

The biggest copper-producing country is Chile, which produces as much as number two and three, Peru and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, combined. But mining production volumes in Chile have barely grown over the past decade. Elsewhere in the world, it is also slow going, less than 2% a year according to the International Copper Study Group.

The industry was particularly spooked last year when protests against a copper mine in Panama – one of the largest in the world – led to the government withdrawing the licence of its Canadian operator, First Quantum. One of the factors behind the unhappiness of the Panamanians is that people don’t like mines in their backyards. This is one of the reasons it can take years to get all the necessary approvals.

None of the above is to suggest that it will be a straight line up for copper or any metals related to the green transition. Market participants have long known copper, or “Dr Copper”, for its ability to diagnose the health of the global economy. Since copper is used almost exclusively in industrial applications, it is a useful cyclical barometer.

In the short term, it could still come under pressure from overcapacity in China, the leading smelter of the metal, for instance. However, short-term price fluctuations are not the story here, the long-term outlook is. Although the copper price is already near record levels in nominal terms, adjusting it for inflation shows that it is not historically stretched by any means.

One unfortunate side-effect of this bullish outlook: theft of copper cable, already a scourge in South Africa, could become a global problem.

No country for old mines

The second question relates to South Africa’s deteriorating reputation as a mining jurisdiction. BHP’s bid pointedly excludes Anglo’s South African operations in iron ore and platinum. Partly, this is because the copper assets are in Chile and Peru, not here. Other potential suitors such as Glencore might be keener on the local operations. Although BHP has denied it is shunning South Africa, it spun off its South African businesses into South32 in 2015.

However, it is hard to escape the fact that South Africa is viewed as an unattractive mining country. The challenges are massive, including volatile labour relations, disputes with surrounding communities, organised crime, regulatory uncertainty, unreasonable delays in processing applications, and infrastructure bottlenecks.

The Fraser Institute, based in Canada, conducts an annual survey on the attractiveness of different countries as mining jurisdictions. These days, South Africa ranks in the bottom ten least attractive mining destinations.

The financial ecosystem that supported junior miners in years gone by has also largely disappeared. Local investors have limited appetite for supporting early-stage mining companies, and global investors have little appetite for any investments in South Africa. Precious little exploration is done, despite geologists estimating that a rich natural bounty remains.

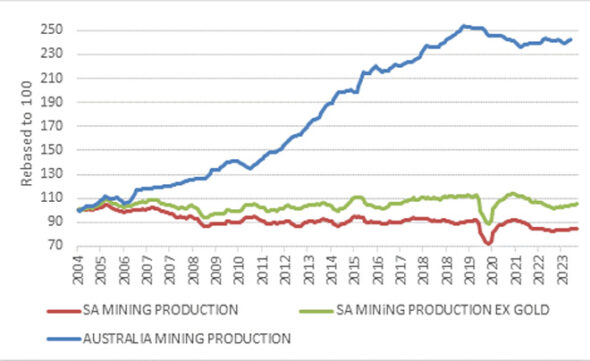

The evidence is in the form of mining production – the volume of stuff pulled out of the ground – which has declined over the past 20 years. Excluding gold, which is arguably largely mined out, makes the picture somewhat better, but not much. In contrast, Australia, not facing the same physical and institutional bottlenecks as on this side of the Indian Ocean, has steadily doubled output over this period.

Real fixed investment spending (gross fixed capital formation) in the mining sector was almost 20% lower in 2023 compared to the 2013 peak. Similarly, mining employment is lower than the 2015 peak of 481 000. And unlike other sectors, Covid cannot be blamed. Covid and its immediate aftermath (and the Russian invasion of Ukraine) saw commodity prices jump.

Mining is still big business in South Africa, and the main source of export revenues. But if output volumes don’t grow, we are entirely reliant on higher prices or a weaker rand for growing export income. And these prices are inherently volatile.

These are glimmers of hope. The relationship between the mining industry and the government is better now than it was in the past 15 years, which can clear some of the regulatory blockages. Mines are now able to diversify electricity supplies away from Eskom and will eventually be able to use trains run by companies other than Transnet. A long-overdue new cadastral system is being procured that should facilitate exploration activity by making it easier to see who owns what mining rights where, speeding up the application process. Many other challenges remain, however.

The shrinking JSE

What about the dwindling list of companies listed on the JSE?

The local bourse started life as a way for gold mining companies to raise capital. Today, it caters to companies from a broad range of sectors, but the basic principle remains. If companies don’t need to raise funding for growth – and in South Africa’s sluggish economy, few do – new listings will be scarce. Since mines remain very capital-intensive compared to other industries, a subdued mining industry as described above is a particularly big constraint.

Part of the problem also lies with a local investor base that is not interested in taking chances on new firms. This is ultimately not good for long-term economic growth and development in South Africa.

Meanwhile, many JSE-listed firms are attractive takeover targets for other companies or private equity funds because they trade at cheap valuations. Anglo is by no means the only one, and unlikely to be the last.

From the point of view of investors, there are still enough companies listed on the JSE to be able to run a diversified South African equity portfolio. Who knows where we’ll be in 10 years, but today many local investors are focusing on spreading their wings abroad. With thousands of international companies from which to choose, no local investor will ever “run out” of investment options.

Notably, this debate is also raging in the United Kingdom and Europe. If Anglo disappears – and it is still a big if – it will also be a blow to the London Stock Exchange (LSE), because it is a FTSE 100 company. The inability of the LSE to attract new listings, especially technology companies, even British companies, is the source of much handwringing.

Markets across Europe trade at a discount to the US, and many companies are considering moving their primary listing to New York to access a broader base of investors and trade at a higher rating. Shell, the Anglo-Dutch oil major, noted last month that it was exploring a US-listing. The European Union is studying steps to unify the fragmented capital markets landscape. Each European country still has its national stock market, from Germany to Greece. Fragmented markets mean a fragmented investor base, impacting liquidity and volume, and arguably dragging on valuations.

Sentiment also plays a role, and the US market is in a far more optimistic space today, buoyed by a strong domestic economy (relative to other major countries) and enthusiasm over AI and other promising technologies. This could change tomorrow.

In contrast, sentiment towards South Africa remains weak, certainly so ahead of the election. But for its many faults, the country has a sophisticated and well-regulated financial system, across banking, insurance, asset management, bond, and equity markets. Perhaps it doesn’t do enough for new and small firms (the JSE is actively looking at steps to reduce the cost and regulatory burden associated with listing, especially for smaller firms), but savers remain well served.

The underlying problem remains that South Africa needs faster economic growth, and getting there requires a more business-friendly environment than we currently have, including the mining sector. This must be a priority for the incoming government.

A favourable global environment also matters greatly. In the pre-2008 commodity boom, investors largely ignored the country’s shortcomings and poured in the dollars, as was the case in several previous commodity upcycles. This can happen again. The question is whether companies, investors, and policymakers are ready to capitalise.

Izak Odendaal is Old Mutual Wealth’s chief investment strategist.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies.

All thanks to the ANC.