The Actuarial Society of South Africa (ASSA) has issued a second communication in as many weeks advising retirees to consider guaranteed annuities as part of their planning for retirement income.

Read: Guaranteed annuity is the better option for most retirees, says Actuarial Society

The latest communication draws attention to the current high annuity rates offered by life insurers, describing them as a “rare rescue package” for living annuitants who are drawing an income at an unsustainable rate.

ASSA encouraged people who are about to retire and living annuity investors relying on unsustainable drawdown rates to consult a financial adviser about purchasing a guaranteed annuity.

The communication quotes ASSA member and an annuity expert Deane Moore as saying that although rising interest rates have inflicted great financial pain on consumers by increasing the cost of living, long-term bond yields have also risen, which means that life insurance companies can afford to offer higher annuity rates.

The country’s 10-year bond yield is at its highest since November 2002, with the result that annuity rates are at highs rarely seen over the past 20 years.

Anyone who buys a guaranteed life annuity now will lock in the current high rates for life.

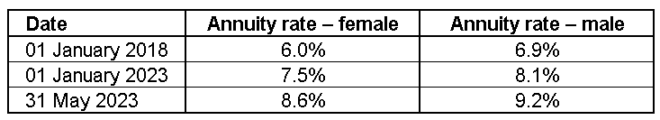

Over the past five years, there has been an increase in annuity rates of 33% for men and 43% for women for guaranteed life annuities, with a 5% annual escalation in income and a 10-year guaranteed period, Moore says.

This means a 60-year-old single woman with retirement savings of R1 million could buy a guaranteed income for life, increasing by 5% every year, of R86 000 a year, compared to R60 000 a year in January 2018. Women generally qualify for lower annuity rates than men because their life expectancy is higher.

‘Lifebuoy’ for living annuity investors

Moore estimates that at least two-thirds of all living annuity investors are living beyond their means and drawing incomes that are whittling away their capital base.

“We are most concerned about people with living annuities who are in their early 70s and drawing income at a rate of 8% or more instead of the recommended living annuity drawdown rate for this age group of between 5% and 6%.”

Living annuity investors who have no choice but to draw incomes above 5% to make ends meet, thereby eroding their capital, have a window of opportunity now to convert their living annuities to guaranteed life annuities, Moore says.

A living annuity investor currently drawing an income of, say, 8% could potentially lock in the same level of income for life by switching to a guaranteed life annuity, because of the current high annuity rates. This would remove the burden of having to worry about what happens when the capital is no longer there to produce an income.

Alternatively, says Moore, some living annuities allow pensioners to buy a guaranteed life annuity as one of their assets, creating a hybrid annuity. “By doing this, pensioners can make sure that their essential living costs are provided for, while the remaining living annuity portion can be given a chance to recover and grow over time.”

Moore says living annuities became popular in the early 2000s, attracting the weight of retirement capital.

“The average life expectancy for men retiring at 65 is another 20 years and for women another 25 years. This means that pensioners who bought living annuities in the early 2000s and who are still alive are effectively the first group of annuitants living beyond the average life expectancy and having to survive on what is left in their living annuities.”

Compounding the woes of living annuity investors were lower-than-expected investment returns, Moore says.

“The past decade has plunged living annuities into a crisis, and we now find ourselves on the cliff edge of that,” he says. The healthy annuity rates currently on offer provide a solution for living annuity investors who find themselves on the edge of that cliff.

Moore says it is a misconception that the life insurance company benefits when the annuity holder dies. Guaranteed life annuities apply the law of insurance whereby a pool of people shares in the risk. The capital left behind by a member of the pool who dies early is used to fund those members who live longer than expected.

For an insurer to be in a position to meet the guaranteed escalating annuity income promised to policy holders, it is assumed that a large portion of the initial client pool payments would be invested where the return is known – in long dated S A government bonds or other secure fixed interest securities. If a 25 year guaranteed annuity is asked for and provided would the insurer seek to match the term of the guarantee to a similar term bond? The current high annuity rates offered must be supported by equally high interest rates on long dated bonds. Should for argument sake, a living annuity be invested in the identical underlying assets to a guaranteed product, why would returns differ? If equities are a better medium to long term asset in respect of returns, versus long dated government bonds, why would a guaranteed annuity underpinned by a lower earning investment be a better option? If the insurer covers the risk of the underlying investments not delivering, then who funds this? Also, who funds the other costs incurred by the insurer? Are these costs recovered from the pool of life annuitants, which must reduce the returns available to cover annuity income payments?