The CCMA’s decision that the dismissal of an employee who refused to be vaccinated against Covid-19 was substantially fair has generated a considerable amount of interest (see our report). Constitutional law expert Professor Pierre de Vos says the CCMA might have come to a different conclusion if the employee had not based her refusal on “misleading and false claims” about the vaccines.

De Vos says several aspects of the CCMA’s arbitration award in the case of Theresa Mulderij vs The Goldrush Group are worth noting.

1. Medical evidence did not support the employee’s claims

The commissioner stated that the decision on the fairness of the dismissal must be taken “in the light of available medical evidence and opinion”.

Although this is not clearly stated in the award, this seemingly presented a significant problem for the employee, Theresa Mulderij, because she advanced several justifications for her decision not to get vaccinated that were not supported by the available medical evidence and opinion, De Vos says.

For example, he says, Mulderij claimed that the World Health Organization had concluded that the vaccine did “not stop the spread or contraction of the Covid-19 virus”, but only minimised the severity of symptoms and side effects. She therefore disputed the premise of the vaccine mandate policy that the vaccine was “for the greater good or well-being of the people around us”. She also claimed that “there was no 100% proof that the vaccination is helping or not”.

These views did not sway the commissioner, presumably because the overwhelming available medical evidence and opinion at the time had consistently found that while vaccines did not completely eliminate the risk of transmission or contraction of Covid-19, it significantly reduced the likelihood of this occurring, De Vos says.

“While the CCMA’s award did not discuss the medical evidence on the efficacy of vaccines, the decision assumes that where vaccines reduce the risk of transmission or contraction of Covid-19 but do not completely eliminate such risk, it may justify the implementation of a vaccine mandate in the workplace, at least in certain contexts.”

He says the emergence of the Omicron variant has “obviously complicated matters”, because the emerging medical evidence suggests that the available vaccines are far less effective at reducing the risk of transmission of the Omicron variant than of earlier variants.

“Whether this will impact on the assessment of the fairness of a dismissal of an employee who refuses to get vaccinated remains to be seen.”

Mulderij claimed during her cross examination that the government could not approve the roll-out of the medication which had “not been approved by the regulatory bodies”.

De Vos says Mulderij’s claim was “obviously inaccurate and misleading”, because all the relevant vaccines used in South Africa had been given emergency approval by the regulatory bodies in terms of the Medicines and Related Substance Act, and the US Food and Drug Administration had given the Pfizer vaccine full approval in August last year.

2. Employer did things by the book

The second important aspect to note was that in this case the company, Goldrush, had, “from its drafting up to its implementation, followed all the crucial steps” prescribed by the regulations that govern the adoption of vaccine mandates by employers.

“The outcome of the case may have been different had the employer failed to follow all these steps.”

3. Safe working environment

In assessing whether the dismissal was fair, the Commissioner accepted that employees did not have an absolute right to freedom of choice, when this choice would potentially endanger others.

After noting the view of the employer that by implication Ms Mulderij was refusing “to participate in creation of a safe working environment of employees”, it indicated that its decision was guided in part by a memo Judge Roland Sutherland, Deputy Judge President of the Gauteng Division of the High Court, had sent to his fellow colleagues.

Based on all these factors, the CCMA concluded that Mulderij was “permanently incapacitated on the basis of her decision to not getting vaccinated and [by] implication refusing to participate in the creation of a safe working environment”.

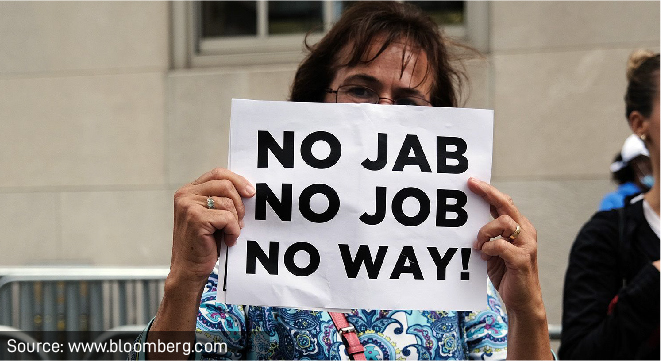

Could objections based on belief sway the CCMA?

“One wonders whether the CCMA might have come to the same conclusion if Ms Mulderij had not based her refusal to get vaccinated on misleading and false claims about the efficacy and safety of Covid-19 vaccines. It is for this reason, I would argue, that the commissioner expressed doubt about the sincerity of Ms Mulderij’s constitutional claim, which he described as ‘ostensibly based on a claim to [the right to] bodily integrity’,” De Vos says.

“Perhaps her position might have been different if she had not based her decision on misleading and false beliefs about the efficacy and safety of Covid-19 vaccines. If this is correct, the small number of employees whose religious or other beliefs require them to refuse all medical treatment, including any kind of vaccination, might find a more sympathetic ear at the CCMA.”

Comment: The CCMA’s ruling is unlikely to be the last word on the issue of mandatory vaccination in the workplace. Indeed, the backlash in certain circles against the arbitration award suggests this matter will end up in the Constitutional Court.

I believe the CCMA has erred in their findings in the Theresa Mulderij case. More and more evidence is coming to the fore that indeed the “vaccine” does not shield humans from contracting the virus. It does however,I believe, only reduce the severity of symptoms once someone does contract Covid 19. I agree that this case will end up in the Concourt, and the finding could well be reversed.