South Africa’s largest open medical scheme, Discovery Health Medical Scheme (DHMS), will make its enhanced screening benefit available to new members after the WELLTH Fund expires at the end of 2024.

DHMS launched the WELLTH Fund in January 2023, to reverse the marked decline in screenings during “the three Covid years”. Screening for cancer and other diseases decreased globally during the pandemic as people avoided hospitals and doctors’ rooms.

“People didn’t go and have their health checks. They didn’t go and see the doctor when they weren’t feeling well. And as a result, we’re seeing more complex disease presenting with more target organ damage, with more risks for long-term health,” said Dr Ryan Noach, who was the chief executive of Discovery Health at the time the WELLTH Fund was launched.

“The time has come to focus our attention on reversing this trend. When it comes to diseases such as cancer or any form of chronic illness, early detection is fundamental to limiting serious complications and reducing costs in the long term,” Noach said. “Our data confirms that on average, a person diagnosed at the age of 40 with an early-stage breast cancer has a three times higher likelihood of surviving for five years post-diagnosis.”

The WELLTH Fund provides the scheme’s members and beneficiaries with access to an expanded range of screening services and to some general primary healthcare benefits to complement the screening.

To use the benefit, members and their dependants (if they have any) must complete a basic health check. Once the results are received, the benefits are unlocked.

Once the WELLTH Fund is activated, each adult beneficiary or single member is allocated R2 500, and children between the ages of two and 18 years are allocated R1 250 each. There is an overall limit per family of R10 000. Children under the age of two do not have to undergo a health check; they have full access to the fund once a primary member activates the benefit.

The once-off benefit is available to current DHMS beneficiaries until 31 December 2024.

However, Deon Kotze, Discovery Health’s chief commercial officer, told Moonstone the WELLTH Fund will be available to people who join DHMS in 2025 and in subsequent years. They will have access to the benefit for the first two years of their membership.

To clarify, post-2024 access to the fund does not apply to new beneficiaries added by an existing member. It applies to new membership contracts, in which case the member and, if applicable, his or her beneficiaries can access the WELLTH Fund.

“If you’re new to the medical scheme, it’s in your interest and our interest to complete the health check because it gives us a view of your health and helps you manage your benefits in an appropriate way,” Kotze said.

At this stage, DHMS has yet to make a call on whether the scheme will be able to afford to roll over the WELLTH Fund benefit to its existing members after 2024.

Under-utilised benefits

When the fund was launched, Discovery set itself the goal of one million health checks by the end of 2024, with 750 000 in the first year.

Kotze said DHMS had paid for 727 000 health checks by the end of May this year – a 50% increase on 2022 and nearly double the number of checks in 2021. The scheme usually sees an uptick in health checks in the last three months of the year, so that could provide the boost necessary to reach the target of one million check-ups by the end of this year.

A further indication that the incentive is having the desired effect is that 17% of new enrolments in the scheme’s chronic care management programmes have been because of screening to unlock the WELLTH Fund, Kotze said.

Members benefit because they are not living with a condition that is undiagnosed and uncontrolled, while the scheme benefits because these members are now enrolled in a care programme where their condition can be managed, he explained.

Despite the encouraging numbers, Kotze said the WELLTH Fund is an under-utilised benefit, particularly among beneficiaries on the Core (hospital plan) series, who constituted 13% of the scheme’s beneficiaries in 2023. It was “surprising” that these beneficiaries did not avail themselves of the opportunity to access up to R10 000 in day-to-day benefits simply by going for a health check.

Regarding under-utilised benefits, Kotze said more beneficiaries could be making use of the scheme’s Hospital at Home programme, whereby they can, where appropriate, receive full-fledged hospital-level care in the comfort of their homes.

Charlotte Mbewu, DHMS’s principal officer, added that many beneficiaries with chronic conditions were not registered on the scheme’s chronic-care management programmes. If they did, they would have access to a basket of care funded out of risk and tools to manage their conditions better.

Impact on financial performance

The WELLTH Fund is funded from the scheme’s reserves, not annual contributions. Last year, Noach said DHMS had set aside R1.5 billion for the benefit, although the actual cost will depend on how many people use it.

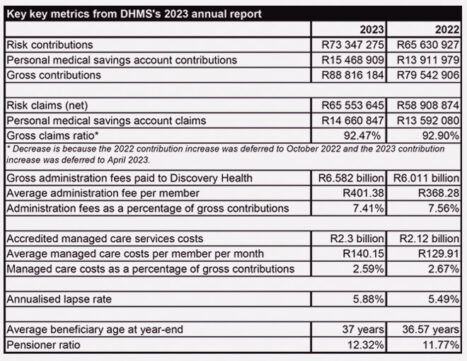

WELLTH Fund expenditure saw the scheme’s reserves decreasing from R28.9bn in 2022 to R28.7bn, resulting in the scheme’s solvency level declining to 35.04% in 2022 to 30.6%. This is still well above the 25% solvency level required by regulation, according to DHMS’s results for the year to the end of December 2023.

As DHMS expected, WELLTH Fund expenditure contributed to the scheme’s insurance service result going further into the red, from negative R1.016bn in 2022 to negative R2.069bn last year. The other contributory factor was the deferral – for the third consecutive year – of the annual contribution increase.

On the plus side, the scheme’s income from investments grew by 9.36% (2022: 6.18%), from R2.221bn to R2.418bn.

Including investment income, the scheme recorded a total comprehensive loss for the year of R182.6 million, compared to a surplus of R1.476bn, excluding amounts attributable to future members (reserves). The WELLTH Fund and the deferred contribution increase contributed R490m and R1.5bn to the total comprehensive loss, respectively, DHMS said.

Where did former members go?

DHMS saw a slight decrease in the number of members and beneficiaries last year. Principal members slipped by 0.12%, from 1 375 544 to 1 373 864, while beneficiaries were down by 0.81%, from 2 818 992 to 2 788 242.

DHMS’s share of the open scheme market remained stable, at 57.8% (2022: 57.6%).

Kotze shared that DHMS recently conducted a survey to find out where members who left the scheme were going. The survey found that 75% of members who left DHMS have dropped out of medical scheme and private health insurance cover completely, while 25% indicated they have taken up another form of cover. Of this 25%, 5% said they have joined a medical scheme offered by their employer.

Changes to Comprehensive series

Last year, DHMS announced that it would reduce the number of plans offered under its Comprehensive series in 2024. The Essential Comprehensive, Classic Delta Comprehensive, and Essential Delta Comprehensive plans were closed, leaving two plans under the series: Classic Comprehensive and Classic Smart Comprehensive.

The annual report shows that 94.67% members did not change their plans between December 2023 and January 2024. Of those who did, 3.15% (about 81 000) upgraded their plans and 2.19% (about 61 000) downgraded.

Kotze said these movements were in line with the scheme’s experience over the past few years, where less than 5% of members have responded to annual contribution/benefit changes by changing their plans.

Mbewu said the scheme made recommendations to members who would be affected by the consolidation of the Comprehensive series, and most members had migrated to the recommended options.

Why so many plans?

Following the consolidation of the Comprehensive series, members and prospective members are faced with a choice of 22 benefit options across seven plan series. It is common for consumers and brokers to bemoan the seemingly excessive number of options – and have to figure out how each one differs.

Mbewu explained that offering a number of options is the medical schemes industry’s response to the regulatory environment. Schemes are, for example, prevented from risk-rating members (setting contribution levels according to a member’s health and age profile) and are required to cover a package of conditions (the Prescribed Minimum Benefits). The only way schemes can protect their sustainability is by attempting to match benefit utilisation with contributions. Furthermore, offering a range of plans provides members with a choice “price points” that align with what they can afford.

Kotze added that, considering the size of DHMS compared to other open schemes, it is not unreasonable to have different plans per series. For example, if the Keycare series (226 848 members at the end of 2023) were carved out of DHMS, it would be the second-largest open scheme in South Africa. It was not practical to offer one plan to meet their diverse healthcare needs, while providing options when it came to the contributions they could afford to pay.