Education expenses have risen sharply this year, jumping by 6.3% compared to last year, according to Statistics SA’s consumer inflation data for March.

Education fees are surveyed once a year in March. Stats SA’s data shows that this year’s increase surpasses the 5.7% annual rise in 2023 and is the highest since 2020, when the rate was 6.4%.

High schools saw the largest fee increase, at 7.3%. Primary schools and tertiary institutions both raised their fees by 5.9%. Crèches increased their fees by 6%. University boarding costs have jumped by 8.2% compared to last year.

The rise in education costs was named one of “the biggest movers in March”, along with miscellaneous goods and services (up 8.5%), health (6%), and housing and utilities (5.9%).

According to Stats SA, the increase in miscellaneous goods and services was mainly driven by higher health insurance premiums in February – an increase of 12.9% in 2024.

The 6% annual rise in the health index was driven by increased prices of medical products and medical services, Stats SA said.

Despite these recent price hikes, the overall inflation rate has eased. In March, headline inflation dropped to 5.3% from 5.6%

One reason for the drop is a reduction in food inflation.

Stats SA reported that food inflation reached a three-and-a-half-year low in March. Inflation for food and non-alcoholic beverages fell to 5.1% in March from 6.1% in February. This is a significant drop from its peak of 14% in March 2023, making it the lowest annual increase since September 2020 when it was 3.8%.

Bread and cereals saw a softer annual increase of 5%, down from February’s 6.1%. The rate is much lower than the high of 21.8% in January 2023. Items such as bread flour, pasta, rusks, maize meal, ready-mix flour, and white bread are now cheaper than they were a year ago.

Meat prices also fell in March because of lower beef and mutton prices. The annual rate for meat in March was 0.8%, a significant decline from the peak of 11.4% in February 2023.

However, annual inflation for sugar, sweets, and desserts has stayed above 15% since June 2023. In March 2024, the rate reached 17.8%.

Some products experienced significant price increases, including brown sugar (up 22%), white sugar (20.1%), chocolate slabs (17.9%), and chocolate bars (15.9%).

When inflation becomes personal

So, with the overall inflation rate down, why does it still feel like we are paying more?

Paul Hutchinson, sales manager at Ninety One, says many of us intuitively think that our personal inflation rate is higher than the Stats SA calculated inflation rate. But is it?

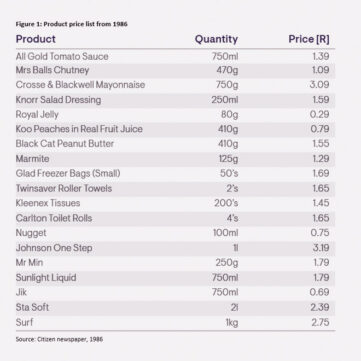

Attempting to answer this question, the prices of products listed in a clipping from The Citizen newspaper of 1986 were compared to what you would pay for them today.

While Hutchinson admits that it does not allow for a robust study of inflation “and is not a representative basket of goods”, he says it does provide some interesting insights and important financial planning lessons.

He points out that many of these items are Tiger Brands’ products, which have not been substantially value-engineered since then.

“For example, Crosse & Blackwell mayonnaise still uses the same recipe, and it still comes in a glass bottle. This makes them good products to analyse over time,” he says.

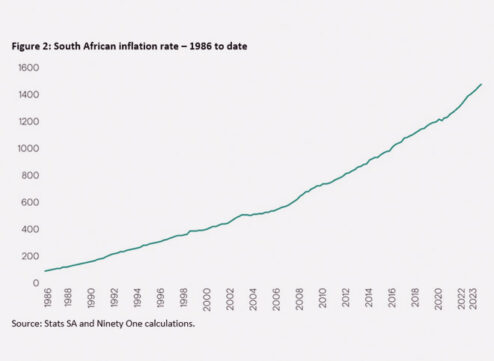

A chart tracking South Africa’s inflation from 1986 to today showed that inflation averaged about 7.5% a year over this period. In short, Hutchinson says, if you made R10 000 a year in 1986, you would now need to earn R150 000 to match the rise in inflation.

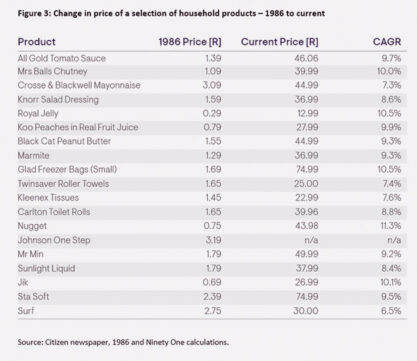

To determine how the changes in the prices in the clipping matched the change in inflation, the team at Ninety One compared the respective product price from 1986 to the current price and calculated the annual compound change from 1986 to today.

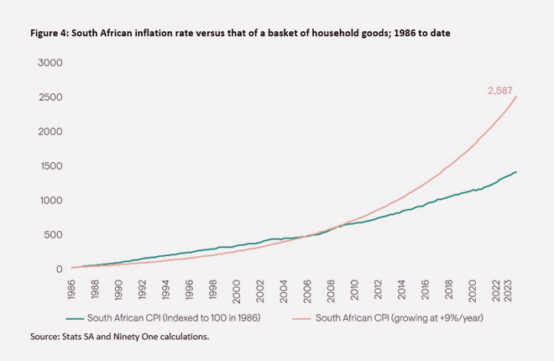

“The average annual increase of 9.1% of this household goods basket is above the official annual inflation rate of 7.5% over this period. So, our intuition that our personal inflation rate is higher than what the official Stats SA inflation rate would suggest does not appear to be so far off the mark,” says Hutchinson.

He adds that the chart showed that just to keep up with the increase in the household goods basket, you now need to earn about R260 000, not R150 000.

What this means for investors

According to Hutchinson, the above analysis indicates that hiding in cash or cash plus, enhanced cash, or income-yielding investment solutions is not a sustainable long-term investment strategy.

He says investors often underestimate for how long they will be invested.

“Simply, if you consider someone entering the workforce today, it is reasonable to assume that they have a 70- to 75-year investment time horizon (40+ years of investing for retirement and then 30 years of living off their accumulated investments in retirement).

Hutchinson adds that although this is an extreme example, even someone mid-way through their working career realistically has a 40- to 50-year remaining investment time horizon.

“And unfortunately, underestimating your investment time horizon often results in investors being too risk-averse about what should be viewed as long-term investments.”

He thinks that, at the same time, investors need to target material outperformance of inflation, noting that all CPI+ benchmarked funds are benchmarked to the Stats SA-calculated inflation rate, not our intuitive inflation rate.

“Therefore, a growth-oriented investment solution is best suited for investors looking to ensure a comfortable and sustainable retirement. This is because it is through investing in growth assets that you can confidently generate attractive real returns over the long term after tax and inflation.”