Solidarity will ask for President Cyril Ramaphosa to be held in contempt of court, accusing the government of breaching an agreement on employment equity. The move comes after the trade union sent a letter to the president on 23 April, urging him to honour the 2023 settlement or face legal action.

At the heart of the dispute is a court-sanctioned agreement signed on 28 June 2023 between Solidarity and the government. The deal, facilitated by the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration supervised by the International Labour Organization (ILO), aimed to resolve concerns over South Africa’s race-based employment legislation. It was intended to guide the implementation of the Employment Equity Amendment Act, which came into force on 1 January 2025.

Read: Government and Solidarity sign agreement on employment equity

However, when the final 2025 Employment Equity Act (EEA) regulations were published on 15 April by the Minister of Employment and Labour, Nomakhosazana Meth, Solidarity says large portions of the agreement had been omitted – despite a court order requiring its inclusion.

According to Solidarity, among the dropped provisions were safeguards stating that no employee should lose their job because of affirmative action, that race must not be the sole criterion in employment decisions, and that such measures must be temporary and constitutionally sound.

Solidarity believes the omissions were intentional.

“It is worrying that the sections that were omitted, among other things, stipulate that no one may be fired based on race laws, that race laws must be temporary, and that skills and the inherent requirements of the job must be taken into account. The government clearly wants to intensify the racial dispensation in South Africa,” said Solidarity chief executive Dr Dirk Hermann.

The union now plans to challenge not only the government’s compliance with the court order but also the rationality and legality of the regulations. It will also file a formal complaint with the ILO, accusing the government of breaching an agreement reached under the ILO’s oversight.

In an analysis of the Determination of Sectoral Numerical Targets and the Employment Equity Regulations 2025 published on 15 April, legal experts from Bowmans, Melissa Cogger and Talita Laubscher, confirmed that some of these concessions did not survive into the final regulations.

“For example, the 2025 EEA Regulations do not explicitly contain the principle ‘no employment termination of any kind may be effected as a consequence of affirmative action’. The principle that ‘affirmative action shall be applied in a nuanced way’ is also missing from the 2025 EEA Regulations. However, the regulations do outline guidelines for implementing affirmative action.”

Are the sectoral numerical targets equivalent to a quota?

The final sector target regulations establish five-year numerical employment equity targets for “designated” groups across 18 economic sectors. These sector-specific targets – and the way the 18 sectors have been defined – have long been a source of contention.

Cogger and Laubscher note that, as with the 2024 draft sector targets, the final sector targets are set for men and women from “designated groups” generally and are not broken down further per population group.

“Further, and as previously recorded in the 2024 draft sector targets, the five-year sector targets are not intended to add up to 100%, as the sector numerical target excludes white males with no disabilities and foreign nationals as part of the workforce profile,” they write.

The 2023 Employment Equity Amendments and 2025 EEA Regulations Guideline (Fifth Edition), published by Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr (CDH), outline how the five-year targets for each of the 18 economic sectors are structured.

“Designated groups” are defined in the Act as black people (Africans, Coloureds, and Indians), women, and people with disabilities who are South African citizens by birth, descent, or certain conditions of naturalisation.

According to CDH, “The targets continue to focus on top and senior management, as well as professionally qualified and skilled levels and people with disabilities. The target for people with disabilities includes all people with disabilities, irrespective of race or gender.”

Although each sector has a single target differentiated only by gender, employers are expected to meet these as minimum goals to promote equitable representation.

“The five-year sector targets are minimum targets which an employer is expected to achieve with a view to improving the equitable representation of people from the different designated groups at various occupational levels,” the law firm notes.

The question of whether these targets amount to quotas was a key source of debate when the draft regulations were first released. The concern, as CDH explains, is that “the sectoral numerical targets set by the minister may constitute a rigid quota and therefore potentially render the application of the sectoral numerical targets unconstitutional”.

However, the Department of Employment and Labour (DoEL) maintains that the targets are intended to be flexible.

“The view of the DoEL is that there is a built-in flexibility for employers to set their own targets on an annual basis with the aim of achieving the five-year sectoral targets published by the minister,” CDH states.

The guideline further clarifies the legal distinction between a quota and a target.

“A quota is rigid, or applied rigidly, and amounts to job reservation,” the firm explains. “On the other hand, a target is a flexible employment guideline. Quotas are prohibited because they constitute an absolute barrier to the future or continued employment or promotion of people who are not from designated groups.”

Section 15 of the EEA prohibits designated employers from implementing any policy or practice that creates such an absolute barrier. Meanwhile, the amended section 15A grants the minister the discretionary power to set numerical targets – provided there is consultation with stakeholders and input from the Employment Equity Commission.

“Importantly, this is a discretionary power and requires consultation with the relevant sectors and the advice of the Employment Equity Commission,” the guideline states. “The outcome of this exercise should ideally result in the minister setting numerical targets based on the reality of the sector, the composition of the workforces within the sector, and the shifting needs for certain skills or proficiencies. This means that the target should be neither arbitrary nor rigid,” the guideline reads.

Transparency and methodology questioned

In their analysis, Cogger and Laubscher highlight several key differences between the draft and the finalised targets, describing the increases as “notable”.

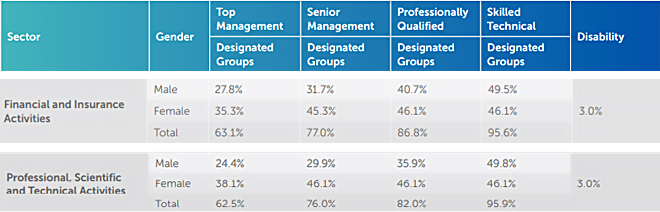

Overall, the final sector targets are significantly higher than those proposed in 2024. The most substantial adjustments affect female representation in senior management roles. For instance, in the Finance and Insurance sector, the target for women in senior management has jumped by 21.3% compared with the 2024 draft sector targets. A similar spike is seen in the Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities sector, where the target for senior female managers has increased by 23.1%.

Although the targets for women have increased across several sectors, there have been some downward adjustments for men in designated groups, although these are less pronounced.

Another prominent change is the revised target for the employment of persons with disabilities, which has been raised from 2% to 3% across all sectors.

But how did the government arrive at the final employment equity targets set out in the regulations published on 15 April – and was the process transparent and inclusive enough to ensure meaningful engagement with stakeholders?

According to Cogger and Laubscher, the DoEL has not disclosed how it determined the final targets, in contrast to its approach in 2024.

“For example, it does not refer to the latest workforce profile statistics, the EAP [Economically Active Population], the various sector codes published under the BBBEE Act, or the unique sector dynamics,” they note.

The employment equity targets apply across 18 national economic sectors, based on the broad categories in the Standard Industrial Classification Codes. These include Financial and Insurance Activities; Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing; Construction; Education; Manufacturing; Mining and Quarrying; Public Administration; and Wholesale and Retail Trade.

These classifications were first published in the Draft 2018 EEA Regulations on 21 September 2018. Since then, they have remained unchanged, despite repeated submissions from organisations pointing out that the sectors are overly broad and fail to reflect the specific circumstances of various subsectors.

In February 2025, the DoEL convened virtual consultations with sector stakeholders and invited written submissions on the new draft targets – known as the 2025 Draft Targets –within a tight deadline. But, as Cogger and Laubscher point out, “Importantly, those draft targets shared in February 2025 were not published in the Government Gazette for public comment.”

Following the virtual sessions, a number of stakeholders participated in bilateral meetings with the department throughout February and March to seek clarity on the rationale behind the proposed targets and the decision to retain the same sector classifications.

During these engagements, the DoEL indicated that the 2025 Draft Targets had been informed by earlier public input, updated workforce profile statistics, and the current dynamics in each sector.

“The DoEL indicated that the rationale for the change in draft targets was due to various sectors comparing well and exceeding the 2024 Draft Sector Targets in the last reporting period, which appears to explain the markedly increased and different Final Sector Targets,” Cogger and Laubscher write.

The department also shared some insight into its methodology – or “formulae” – during these consultations.

“The DoEL considered the workforce profiles of the various sectors for 2023 and 2024. It then set the target for the top four occupational levels at 6%, 7%, 8%, and 9%, respectively. This appears to be based on the DoEL’s view that these are appropriate targets. The Final Sector Targets therefore do not appear to have been formulated on any scientific or empirical basis.”

This approach, they warn, has created practical challenges for several subsectors. “In some instances, the targets are then much higher than the 6% to 9% principle applied by the DoEL, which makes compliance with the sector targets a challenge for these sub-sectors.”

First compliance check set for 2026

The amended employment equity (EE) targets, now in effect, set the stage for the first compliance assessment in the 2026 reporting cycle.

Employers have until 31 August 2025 to complete a workplace analysis and update their EE plans to align with the new sectoral targets, according to CDH. The upcoming reporting period runs from 1 September 2025 to 15 January 2026, but initial submissions will not be assessed against the five-year targets.

As CDH notes, “employers will not be evaluated on their progress towards achieving the five-year targets for this initial reporting cycle. The first assessment… will commence in 2026.”

Non-compliant employers risk penalties of up to R1.5 million or 2% of annual turnover, whichever is greater. However, the regulations outline seven valid grounds for non-compliance, including lack of recruitment or promotion opportunities, economic hardship, or legal constraints.

Despite the strict tone of section 20(2A), Cogger and Laubscher point out that established legal principles still apply.

“Section 15(3) explicitly states that affirmative action measures include preferential treatment and numerical goals, but exclude quotas, and that there should not be absolute barriers to the appointment or promotion of over-represented groups,” they note.