The “important and unprecedented decision” by the Financial Services Tribunal (FST) to dismiss the reconsideration application brought by members of the board of the Private Security Sector Provident Fund (PSSPF) has “far-reaching implications” for trustees and principal officers, the FSCA says.

In August 2022, the FSCA took regulatory action against 10 current and past members of the PSSPF’s board, as well as the principal officer, after finding they were no longer fit and proper to hold office. In this regard, the FSCA exercised its authority in terms of section 26(4) and (5) of the Pension Funds Act (PFA).

The FSCA found the board members had, among other things, engaged in improper procurement practices and enriched themselves via excessive fees for meetings and travel allowances.

The PSSPF oversees the retirement, funeral, and death benefits of security guards. It has 330 000 active members and assets of more than R11.5 billion.

The PSSPF was taken out of statutory management at the end of April.

Read: Statutory management of Private Security Sector Provident Fund to end

The background to the FSCA’s decision to sanction the board members is narrated in these articles:

- FSCA takes action against Private Security Sector Provident Fund trustees

- Behind the scenes of an FSCA investigation

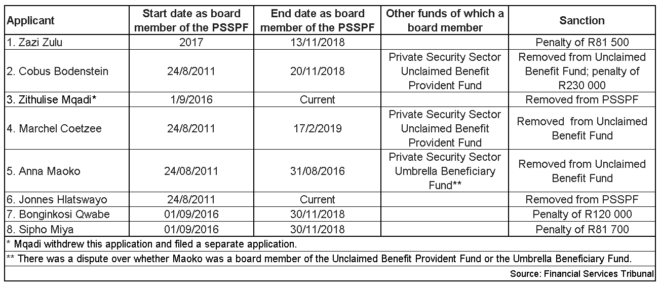

The sanctions imposed on the eight board members who lodged the reconsideration application are set out in the table below.

The tribunal dismissed the consolidated application brought by Zulu, Bodenstein, Coetzee, Maoko, Hlatswayo, Qwabe, and Miya, as well as the separate applications brought by Mqadi and principal officer Mziwandile Zibi.

The three inter-linked decisions were handed down on 9 May.

Points of law

This article will first look at the FST’s response to some of the points of law raised by the applicants.

‘Fit and proper’ has general application

As the table shows, three of the applicants who were no longer members of the PSSPF’s board were ordered to vacate their positions as board members of other funds.

The applicants argued that an order cannot be made that a person who misbehaved in respect of one fund is held not to be fit and proper to be a board member of another fund.

The FST said fitness to hold office is not related to the business of any particular fund. “It is an objective question and of general application. To use an example: a board member who robs a bank is not a person who is fit and proper to hold office of any fund. And the way a board member acts in relation to the affairs of one fund quite clearly reflects on that member’s fitness in relation to another fund: one cannot defraud fund A and be a person fit and proper to be a board member of fund B.”

Section 167 did not create an offence

The FSCA imposed the penalties in terms of section 167 of the Financial Sector Regulation Act, which came into effect on 1 April 2018.

The applicants argued that the “alleged wrongdoings” – contraventions of section 7C of the PFA and section 2 of the Financial Institutions (Protection of Funds) Act – were committed before section 167 came into operation. They submitted that section 167 created an offence but did not do so retrospectively and there was a presumption against retrospectivity.

The FST said section 167 did not create an offence. It created jurisdiction for the imposition of administrative penalties for “contraventions” of financial sector laws.

The presumption issue did not arise, because a breach of the PFA and section 2 of the Financial Institutions Act have always been subject to an administrative penalty.

Board ignored the fund’s procurement policy

The FST said the “bare facts” that resulted in the FSCA’s decision were not disputed, and the applicants’ “lame excuses” were “hardly worthy of serious debate”.

The circumstances surrounding the appointment of Salt Employee Benefits as the fund’s administrator were the trigger for the FSCA’s initial investigation into the PSSPF four years ago.

The FST said it was common cause that the board ignored the fund’s procurement policy for a prolonged period.

“The excuse was that the policy did not bind the board – in other words, the fund had a policy which the board could freely ignore. How ignoring a fund policy wholescale can be equated with a unanimous consent (in company law) is not understood. Even if one assumes that any procurement policy established by a board can be ‘amended, overruled or withdrawn’ by a board, the fact is that the board never sought or purported to amend, overrule, or withdraw the policy. It simply ignored it under suspicious circumstances.”

Even if it were assumed that the procurement policy was not binding, the process followed in relation to the Salt tender illustrated that the applicants “failed in their fiduciary dues and are incompetent and could not be considered persons who are fit and proper to be entrusted with fiduciary dues”, the FST said.

It said the facts of Salt’s appointment were:

- The fund followed a closed bidding process without justification and despite legal advice to the contrary.

- The fund shortlisted Salt as a service provider despite its failing to meet the requirements in the tender specification document, which lacked the selection criteria prescribed in the procurement policy.

- The fund concluded a service level agreement with Salt in terms of which the costs ballooned. The fees ultimately charged by Salt exceeded the quoted amount by more than R2.7 million a year.

- The fund agreed to pay Salt R17.1m as a “take-on fee” because it did not have the capacity to take on the fund, which was not mentioned in the tender proposal.

- The fund agreed to pay Salt nearly R33m to load historical information, with 50% payable before any work had been done.

- Shortly after it was appointed, Salt made various unexplained donations to organisations closely associated with board members who had supported its appointment. It even purchased business class plane tickets for Bodenstein and his wife to attend the Sevens Rugby Tournament in Hong Kong the following year, none of which was disclosed.

Remuneration and self-enrichment

The tribunal’s decision set out the following regarding the remuneration of the board members:

- The cost of board meetings including fees, travel, and accommodation for 2016 was R21m and for 2017 more than R25m. The comparable cost of a fund with similar membership and assets was at the time about R1.2m.

- The rates paid to board members during 2017 exceeded the fund’s remuneration policy; chairpersons of sub-committees received a fixed monthly fee in addition to a fee for attending meeti

- The board held 493 meetings in a year, including eight in a single month for purposes of organising a golf day (attendance at which was remunerated), 55 meetings in March 2017 at a total remuneration of more than R2m, and 66 meetings in June 2017 at a total remuneration of more than R3m.

- The average allowance (including travel reimbursements) between August 2016 and September 2017 equated to R74 518 per member (not employed full-time) a month.

- Seventeen members attended a Batseta Conference from 29 to 31 May 2017 at Sun City. The fund incurred expenses of R540 295 in respect of remuneration for attendance of this conference in addition to other travel, accommodation, and conference costs.

- Various meetings were held prior to, during, and after the conference that cost a further R379 039.

The FST said “no one could honestly believe” that these meetings and fees were justified, and the board members “abused their fiduciary position for self-enrichment”.

FST might have fined all the board members

Only four of the applicants were fined, with the amounts calculated at 10% of the fees each had received.

The FST said the penalties were objectively appropriate – “if not too low”, because they were determined with reference to the remuneration-linked contravention but disregarded the impropriety relating to the tender processes.

There was no explanation why the other applicants were not fined, which provided a basis for the four applicants to claim unequal treatment, it said.

However, that the FSCA “erred” in failing to fine the others did not mean the penalties imposed on the four were not appropriate.

“Had the issue been raised with prior notice, we might have considered imposing penalties on the others in the exercise of our discretion.”

‘Important and unprecedented decision’

The FST’s ruling has far-reaching implications for trustees and principal officers because it confirmed the powers of the FSCA to remove such officers from the boards of funds, as well as the feasibility of imposing penalties in the personal capacity of such representatives, the FSCA said in a statement on 12 May.

“The judgment reiterated the role and responsibilities of a principal officer and confirms the view of the FSCA that a principal officer holds a fiduciary responsibility towards the stakeholders in the fund. The tribunal further agrees with our view that we can take action irrespective of the office you hold [at] other funds,” it said.

“This is an important and unprecedented decision for the retirement fund industry, as it upholds the importance of good governance and prudent conduct by trustees and principal officers of retirement funds,” the Authority said.

“The FSCA expects both trustees and principal officers to comply with their fiduciary duties and to conduct themselves ethically, lawfully, diligently and properly.”

Download the FST’s decisions in Zulu et al and in Mqadi.

Talk about an efficient private sector retirement fund working for the benefit of members. This was pure money laundering in disguise by board members. Some of them you might be owners of the same security companies they represent. Fit and proper requirement flawed. Good article.