Benjamin Franklin’s timeless advice, “Don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today”, rings particularly true for financial advisers who, despite the clear necessity, often delay succession planning – only to face rushed and potentially disastrous transitions later.

At the recent 2024 FPI Professional’s Convention in Cape Town, Jaco van Tonder, the head of Advisor Services at Ninety One, delved into the critical topic of succession planning. His presentation, titled “Succession planning: The pitfalls and how to avoid them”, provided a practical framework designed for wealth management practices, with relevance extending to medical schemes and short-term insurance.

Van Tonder addressed the complexities of retirement, explored various succession planning models, and discussed succession valuation. His insights emphasised the necessity of preparing for the future, not only to secure advisers’ legacies but also to ensure continued client service.

When and how do advisers retire?

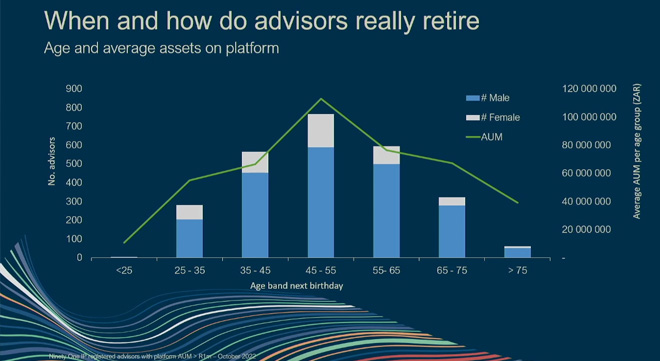

Using data from the end of 2022, Van Tonder presented a snapshot of the advisory landscape.

He urged advisers to build their succession plans on the “four age pillars” he identified: the lack of wealth accumulation under the age of 25, the robust succession pool in the 25 to 45 age group, the peak asset-building years from 45 to 55, and the extended work life beyond 65. He said that by grounding their plans in these age realities, advisers can set themselves up for a smoother transition and a more successful exit from the business.

“The first message we should take away,” he noted, “is that there appears to be quite a large number of young and upcoming advisers in the 25-to-45 age group who are the succession plans for the future.”

Contrary to the belief that the advisory industry is ageing and at risk of decline, Van Tonder’s data disclosed a healthy distribution of ages, suggesting the future of the industry is secure, at least within the wealth management sector.

However, he also highlighted a critical issue: the scarcity of younger advisers under the age of 25 who have built meaningful books of business.

“Very few wealth advisers build up any meaningful book before age 25, and we all understand that,” he said, adding that younger advisers are still in the early stages of their careers.

He cautioned against unrealistic succession plans that involve appointing someone too young , noting that “to have a realistic internal, organic succession plan, you’ve got to target a succession candidate who would be at least age 35 when they’re starting to move into that ownership space”. “Before that, they simply do not have the book and they do not have the financials,” he said.

Van Tonder’s analysis also showed that advisers tend to accumulate their largest assets between the ages of 45 and 55, underscoring the importance of choosing successors who are financially and professionally mature.

“Advisers work for very long periods of time,” Van Tonder observed, pointing out that many continue working well beyond the traditional retirement age. “As a matter of fact, 50% of advisers work beyond age 65,” he added, a statistic that has significant implications for succession planning.

The extended working life of advisers can complicate the transition process for successors, who may be eager to take over but find themselves in a prolonged waiting period. Van Tonder advised a pragmatic approach: “Plan to work later, and then leave earlier if all goes well. That is better than the other way around, where you plan to leave early and then hang around.”

The four models of succession

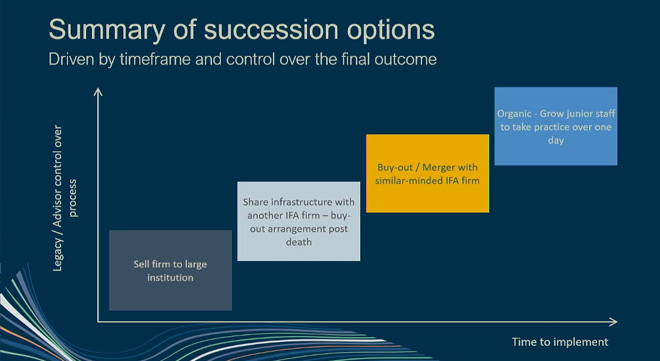

Van Tonder outlined four distinct models for structuring a succession plan, each with its own implications for timing, control, and legacy preservation.

The first model is selling to a large corporate institution.

“You can do that pretty quickly,” he said, pointing out that well-orchestrated deals can be completed within 12 to 18 months.

However, he cautioned that this model comes with a significant trade-off: loss of control. “Even if people promise you low levels of interference, if they have full control, they will do what they need to do to deliver the earnings,” he said, emphasising that the buyer’s return on equity will dictate decisions, regardless of any handshake agreements.

The second model involves two companies sharing infrastructure while remaining separate entities. This approach, which he compared to a “living together relationship”, allows firms to benefit from shared resources without fully merging.

“We’re not getting married and setting up a formal business,” he explained, highlighting the flexibility of this model. However, it requires careful planning to ensure both parties are protected in the event of unforeseen circumstances like critical illness.

The third model, which Van Tonder referred to as “getting married”, involves a formal merger between two firms. This approach typically includes a shareholder sale or share swap, resulting in a single, unified entity.

“That one is quite popular at the moment in South Africa,” he observed, noting it provides a clear path to integration and continuity.

The organic succession model, the final model, is the option to which most advisers aspire.

“It’s the dream,” he said, acknowledging that many advisers prefer this approach because it allows them to maintain full control over their business and preserve their legacy.

“The clients deal with the same brand. It’s the least disruptive option,” he added. However, he also pointed out the significant downside: “It takes time, and it takes more time than most people realise.”

The organic succession model

This approach allows the founder to dictate the pace of the transition, retaining control over the business until they decide to retire completely.

“You can see now why they like this,” he remarked, noting that entrepreneurial advisers often have a strong desire to keep a “hand on the tiller”.

However, Van Tonder said this model, despite its appeal, comes with significant challenges.

“The problem is that it takes at least a decade, and that’s if everything goes right, which it rarely ever does,” he cautioned.

The primary obstacles include recruiting and retaining talent, and securing the necessary funding for the successor to buy out the business.

Even for those advisers who manage to navigate these hurdles, another critical issue arises, which is funding their retirement.

“If you don’t follow your own advice, and you don’t build up an asset base outside of your practice, your succession options become severely limited,” Van Tonder warned.

He said that selling a practice alone typically only funds about half of an adviser’s retirement needs.

“You can only fund half of your retirement by selling your practice. Fifty percent replacement ratio. Whatever you want the replacement ratio to be more than 50%, you’ve got to build on the outside while you run the business,” he explained, underscoring the importance of external investments for a secure retirement.

A formal merger between two firms

With the organic succession model being difficult to execute successfully, more mid-sized firms are entering the market to purchase smaller advice firms, creating a pathway for elderly advisers to transition their practices.

Van Tonder outlined the practical aspects of such mergers, explaining, “In practice, you transfer the clients off of the current FSP and onto the buying FSP, so it’s one entity with two shareholders.”

This consolidated structure allows each partner to draw a salary based on their contributions to revenue, with a bonus pool and dividend split to balance the financial benefits.

The model also offers cost efficiencies, typically through a unified investment process, and includes a shareholding buyout arrangement in the event of a partner’s death to ensure business continuity.

The benefits of this merger model are clear: “You continue your current business ethos, there’s no exchanging of capital, because we’re just each being issued with shares in the same new combined entity,” Van Tonder said.

Importantly, clients experience a smoother transition, because they perceive themselves to be dealing with a more established corporate entity rather than individual advisers. This, in turn, makes the succession impact easier for clients to absorb and navigate, he said.

However, Van Tonder said the downside is that it is difficult to find a candidate for the merger, because “you need to find someone with whom you can get along, and that can be surprisingly difficult”.

He pointed out that mergers are fraught with risks, particularly those related to behavioural science and psychology, which are often underestimated. Additionally, if both parties involved in the merger are elderly, the succession problem remains unsolved. Ideally, the buying firm should have younger advisers to address succession risks effectively.

The shared infrastructure model

Then there is the less integrated alternative: the shared infrastructure model, where firms share office space and expenses but often maintain separate FSPs and financial operations.

This model provides a way for advisers to collaborate without committing to a full merger.

“They can sometimes or not share a central investment process or a DFM, and on death, there is an arrangement for a book takeover by the other party, or there’s a sharing of revenue with a spouse that’s often built into the death arrangements. And again, it keeps the business ethos going,” Van Tonder explained.

This model allows firms to pool resources and reduce overhead costs, while still preserving their individual identities and operational structures.

One of the key advantages of this model is its simplicity. Firms can avoid complex merger processes and focus on maintaining their current operations without the immediate pressures of integration.

“It’s no valuations, no big commitments upfront,” he said. “All the difficult components get deferred to the date of death of the first person.”

However, van Tonder cautioned that this model comes with its own set of challenges.

By deferring the more complex aspects of succession planning, such as valuations and buyouts, to a later date, firms may face significant challenges if not carefully managed. If both partners are elderly, this approach might not effectively address the succession problem, he said.

Selling to a large corporate institution

For advisers looking to exit the business swiftly, selling to a large corporate offers a clear path to the realisation of their practice’s value.

Van Tonder said this model can be “implemented very quickly” and can be “very lucrative if the timing/valuation is good”.

Aligning with a larger entity can also facilitate faster scaling and provide an opportunity for a clean break from the business, allowing the adviser to “quickly walk away from the business if desired”.

However, the transition is not without its challenges.

“In this model, valuation is of critical importance,” Van Tonder warned. Advisers must carefully negotiate terms to ensure they receive fair value for their practice.

Post-buyout, the adjustment from being an independent business owner to working within a corporate structure can be significant. Tensions could arise, including pressures to use in-house products and disagreements over fee splits.

He pointed out that the shift from autonomy to operating within a corporate hierarchy often leads to dissatisfaction, and minor grievances can escalate into major disagreements.

He added that some corporates may attempt to renegotiate the terms of the sale post-acquisition, a move that can leave advisers with limited recourse.

“Typically, that doesn’t end well for the adviser,” he said.

If they decide to sell to a large corporate, Van Tonder suggested that advisers plan for their fixed exit at a certain point in time to avoid many these issues, particularly if financials for the practice are a big part of the reason for the deal.

“Selling to a large corporate can be very effective at realising that value of the business, but then you must not moan and complain about losing control. I mean, those two are the opposite sides of the coin, so understand the benefits and understand that things can go wrong.”

While the older generation of advisors was undoubtedly equipped with valuable knowledge from prominent figures in wealth engagement and financial service providers (FSPs), they often struggle to effectively pass the torch. Sticking rigidly to outdated practices, they fail to address the evolving needs of modern clients, resulting in a decline in personal service and a focus on only a select few. To future-proof advisory practices, it’s crucial to embrace new methods that engage the next generation, ensuring that the personal touch remains central to the profession’s legacy.