The rout in global bond markets since quantitative tightening started in earnest in 2022 to get inflation under control and suppress economic growth has reached crisis proportions, particularly over the past two weeks.

Globally, long-term government bond yields jumped across the board. On Friday, US 10-year government bonds ended the week 0.7% (70 basis points) higher than they did two months ago, German 10-year bonds were 0.4% higher, and South African 10-year government bonds matched the increase in US bonds by closing at 12%, or 0.7% higher.

At the close of the markets on Friday, Bloomberg aptly attributed the jump in rates, or the higher cost of money, to economies being more robust than anticipated, causing expectations of higher interest rates for longer. Governments must refinance debt issued during the pandemic at significantly higher yields, which could result in unsustainable fiscal deficits. Corporate America is undeterred by the rising cost of borrowing and continues the borrowing spree.

The US 20-year government bond yield ended the week at 5.16%, and the 10-year bond at 4.8%.

In an article on Friday, distinguished investment strategist Edward Yardeni commented: “If we see the yield soaring well above 5%, we (along with everyone else) will have to conclude that … (a) debt crisis might have started.”

Something must give, as rising interest rates will increase the cost of living, while the debt burden is increasingly weighing on corporate fundamentals. Yes, the long-furloughed recession may be on the doorstep.

The outlook for lesser-developed countries is grim because the days of debt-financed spending sprees and extravagance are over. On Friday, BBC reported that Kenya, already heavily in debt to China, will be asking for more money to complete abandoned infrastructure projects and is seeking a longer repayment period for existing loans. The wings of extravagant government officials will be clipped, while all ministries were ordered to cut their budgets for the next financial year by 10%.

Outlook for SA debt markets is weak

The outlook for debt markets in South Africa, Africa’s most industrialised economy, remains very weak. The economy is hamstrung by foreign debt investors who went on strike because of mistrust in the government due to incompetence and the legacy of state capture that crippled the economy and society.

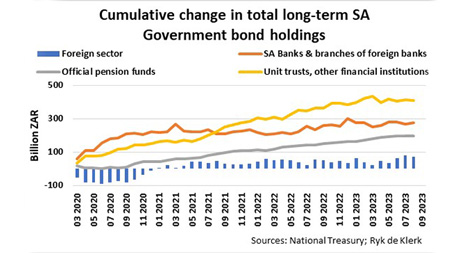

After Moody’s cut South Africa’s investment-grade credit rating to “junk” amid the coronavirus outbreak downgrade in March 2020, the country’s government bonds were kicked out of the World Government Bond Index. According to data from National Treasury, cumulative nominal long-term SA government bond holdings by the foreign sector fell by about R90 billion to R721bn in June that year.

Although foreigners subsequently returned to the market, official holdings by foreigners since May 2021 ranged between R800bn and R900bn. The latest numbers to August this year indicate that official foreign holdings are up R71bn since January 2020. That compares to the cumulative total issuance of long-term SA government bonds of R1 198bn over the same period, resulting in total outstanding long-term domestic loans of R3 378bn (about 56% of South Africa’s total government and state-owned enterprise debt). Yes, foreign investors starved the economy, and local investors effectively had to absorb about R1 100bn. South African banks and branches of foreign banks took up R277bn, official pension funds R198bn, and unit trusts and other financial institutions, excluding insurers, R410bn.

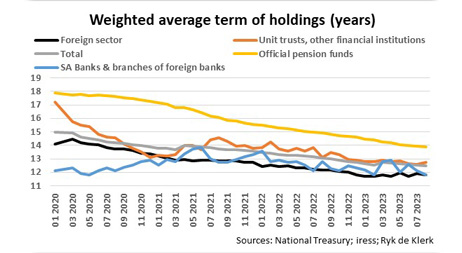

Foreign investors also de-risked their official holdings to some extent. Since May 2021, they shortened the weighted average term of their holdings and modified duration (change in capital value per 100 basis point change in rate) relative to the total issued long-term SA government bonds.

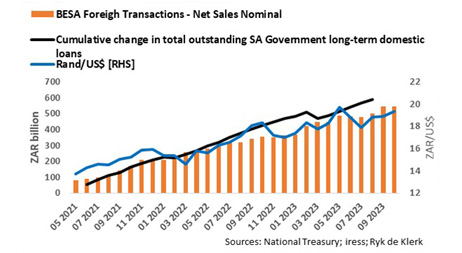

This, however, only tells part of the story because JSE bond-trading statistics reveal that the position with foreign holdings is much worse. Since May 2021, on a cumulative basis, foreigners were net sellers of about R450bn in nominal bonds on the JSE, and despite positive changes in the official foreign holdings of long-term SA government bonds, most of the time foreigners remained net sellers of bonds on the JSE.

Yes, foreigners probably sold most of their bond holdings in state-owned enterprises and hedged dollar or other foreign-currency-denominated long-term SA government debt. It is, however, likely that they hedged their official holdings. Furthermore, it could be that any new purchases or take-ups of new bond issuances are hedged immediately.

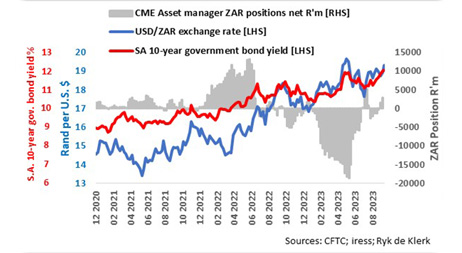

From the accompanying graph, it is also evident that foreign asset managers actively protect their South Africa-related investments against changes in the rand/dollar exchange rate.

But why?

It is a question of the supply of new stock issued. The cumulative net sales by foreigners since May 2021 are positively correlated with the cumulative net issuance of long-term SA government bonds, while the cumulative net foreign sales on the JSE equalled more than 80% of the net stock issued over the said period.

In the absence of foreign buyers, no new foreign funds are flowing into South Africa, while the rand amount of new stock balloons. It is a vicious circle because South African financial entities need to protect the purchasing value of their investments, specifically in the case of long-term bonds, by selling rands and purchasing hard currencies.

The strong relationship between the rand’s external value against hard currencies and long-term SA government bond yields points to the actions by foreign and domestic investors in the SA bond market.

Reality bites

The yield gap between the SA 10-year government yield and corresponding US bonds has been in a downtrend since 2020 and has traded in a range between 7% and 8%. At 7.2% currently, it indicates an upside of 0.8% (80 basis points), meaning that, all other things being equal, the SA 10-year government bond yield could rise to just below 13% from 12% at the close last Friday.

As in the case of Kenya, the government has realised, or should realise, that the days of debt-financed spending sprees and extravagance are over, particularly in the run-up to next year’s election. The global market will talk tough and punish South Africa by demanding higher rates for new bond issuances, as the capacity to absorb new bond issuances has become extremely limited. There is no room for skulduggery and dishing out cash.

Any further sell-off in US and other mature market bonds because of a jump in rates will lead to a concomitant rise in South African bond rates and a further weakening of the rand against hard currencies such as the US dollar, British pound, euro, and Chinese yuan.

Higher rates will reverberate across the global financial system and economies and may cause significant fallouts if not contained.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.