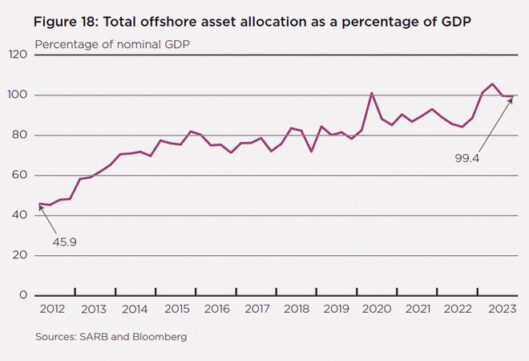

Domestic institutional investors’ total offshore asset allocations were almost the size of South Africa’s nominal GDP at the end of last year, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) said in its first Financial Stability Review (FSR) of 2024.

The country’s nominal gross domestic product at market prices in 2023 was R6.97 trillion, according to Statistics South Africa.

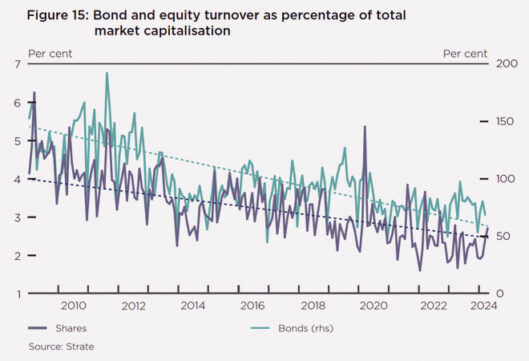

The SARB said domestic investors’ increasingly diversifying into global markets is one of several factors contributing to South Africa’s capital markets becoming shallower and less liquid over the past few years. The other main factors are South Africa’s low rates of growth and domestic saving, the crowding out of private sector debt by the government, and reduced foreign portfolio investment.

The central bank expressed its concern that the shallower and less liquid capital markets mean fewer options for local investors and borrowers and more concentration risk.

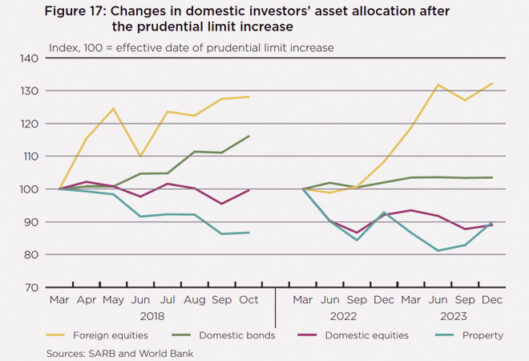

In February 2022, National Treasury increased the offshore prudential limit for South African institutional investors to 45%, inclusive of the 10% Africa allowance.

“The rationale for the decision was that with a shrinking economy, sustained delistings on the JSE, and structurally lower economic growth, the offshore prudential limit increase should offer increased diversification opportunities to domestic investors. The previous increase in the offshore prudential limit for domestic institutional investors was in 2018.

“Following the announcement of the increase in both 2018 and 2022, there was a marked increase in domestic investors’ foreign asset allocation, with a sharp increase in exposure to foreign equities at the expense of domestic equities and exposure to domestic property portfolios,” the FSR said.

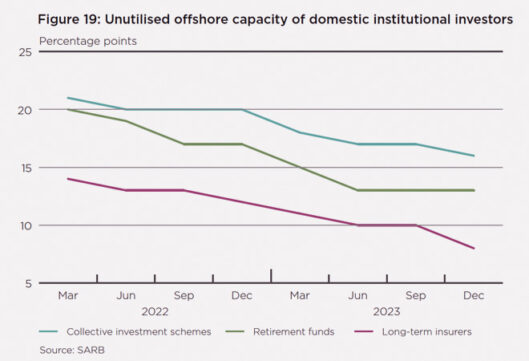

At the end of 2023, the total offshore asset allocations of domestic institutional investors reached 99.4% of nominal GDP, having more than doubled since 2012. As total offshore asset allocation increased, domestic institutional investors’ unutilised offshore capacity decreased, with a marked acceleration since the latest limit increase in February 2022.

The SARB said the increase in the offshore prudential limit has positive and negative implications for financial stability.

“While it may have distributional effects on the domestic capital markets and contribute to a loss of depth and liquidity, it provides diversification opportunities and the possibility of higher earnings for domestic investors. As the aggregate new limit is approached (considering that not all investment mandates allow foreign exposures), it becomes a stabilising factor, as all returns that push exposures over the limit have to be repatriated.”

The FSR said the government has increasingly dominated issuance in the domestic bond market, increasing its share of total outstanding bonds from about 60% in 2008 to 81% at the end of February 2024. Meanwhile, on the JSE, there have been net company delistings every year since 2016. Turnover in the domestic bond and equity markets has also declined in recent years, potentially affecting efficient pricing, investor returns, and the cost of funding.

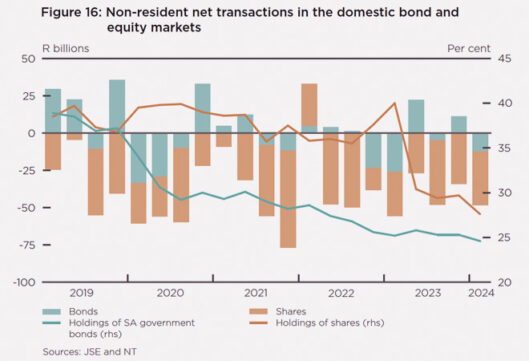

Non-residents were net sellers of R12.4 billion worth of JSE-listed bonds in the first quarter of 2024 after net purchases of bonds to the value of R11.2bn in the fourth quarter of 2023. Continued outflows from the equity market were reflected in the share of non-residents’ holdings of domestic shares, which reached a new low of 27.6% at the end of March 2024, down from 29.7% in December 2023.

Exposure to government bonds is a risk

The SARB also expressed its concern over the extent to which the South African financial system is exposed to government debt.

Government bonds comprise a high and growing proportion of financial institutions’ balance sheets, potentially crowding out lending to or investing in the private sector, exposing the financial system to market risk in the event of a sharp repricing of government debt, and undermining market resilience as the financial system is increasingly exposed to a common risk.

“A higher concentration of government bonds on domestic financial institutions’ balance sheets also inhibits the capacity of the domestic financial system to absorb financial shocks. It may also lead to increased high-volatility, low-liquidity episodes in the domestic bond market, which would impair price discovery and represent a deterioration of trading conditions for South African government bonds that could spill over to the rest of the financial market. In turn, the overall resilience of the domestic financial system is reduced,” the FSR said.

The government’s relatively large financing requirements are putting upward pressure on government bond yields and increasing funding costs across the financial system.

As borrowing costs in the economy are linked to the yield curve, an upward shift and steepening of the yield curve result in higher funding costs for public and private sector borrowers. This could make more long-term investment projects unviable and create a negative feedback loop between the elevated debt levels and debt-service costs. This has a lasting dampening impact on potential economic growth, the SARB said.

Deteriorating fiscal position

The SARB once again flagged the deterioration in South Africa’s fiscal position over the past decade, noting the growth in the cost of servicing debt.

As global interest rates are expected to remain high for longer and the outstanding debt that the government must service has increased, South Africa’s debt-service costs are projected to remain above 20% of main budget revenue in the medium term, well above its long-term average of 13%, it said.

South Africa’s debt stands out compared to other emerging markets. South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio of 73.7% is well above the emerging-market average of 58.9%, and its interest-to-GDP ratio is 4.7%, compared to the emerging-market average of 3.1%.

The SARB said the R150bn draw-down on the Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account is anticipated to moderate government debt somewhat. Government debt is now expected to peak at 75.3% of GDP, as opposed to the previous 77.7% of GDP announced in the 2023 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement.

Nevertheless, it said South Africa’s fiscal accounts remain under pressure from spending on non-growth-inducing priorities – for example, debt-service costs and financial support to state-owned enterprises – and slow economic growth.

South Africa’s elevated debt ratio, coupled with high borrowing costs, means that debt-service costs continue to be one of the fastest-growing expenditure components for the government, the FSR said.

“The initial stagnation and subsequent decline in real social spending in recent years have impaired the government’s ability to fund the provision of public services, such as healthcare, education, housing, and social protection. Given the extent of inequality in South Africa, a reduction in the availability and quality of public services and the social safety net exacerbates the already elevated risks to social cohesion.”