It is prudent to assume that the proposed value-added tax (VAT) increase of one percentage point over two years will be passed by Parliament, says Gerhard Badenhorst, director in Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr’s tax and exchange control practice.

Businesses will have to review their accounting, point-of-sale, and billing systems, as well as the reports they generate from their systems to complete their VAT returns.

This will not only be time-consuming, but it will also come at a cost, says Aneria Bouwer, senior consultant at Bowmans. “It is unfortunate that the VAT increase is phased in over two years because implementation is time-consuming, with more administrative issues for VAT vendors. That means additional costs.”

Read: VAT hike | Guidance for businesses on supply rules and timing

Impact on inflation

Another “cost” is the impact on inflation. Annabel Bishop, Investec’s chief economist, says a two-percentage point increase would have pushed the inflation rate up by 1% over 12 months. The one-percentage-point increase over two years will increase inflation by 0.5% over 24 months.

Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana proposed the VAT increase after his first Budget was delayed when key partners in the Government of National Unity rejected the increase.

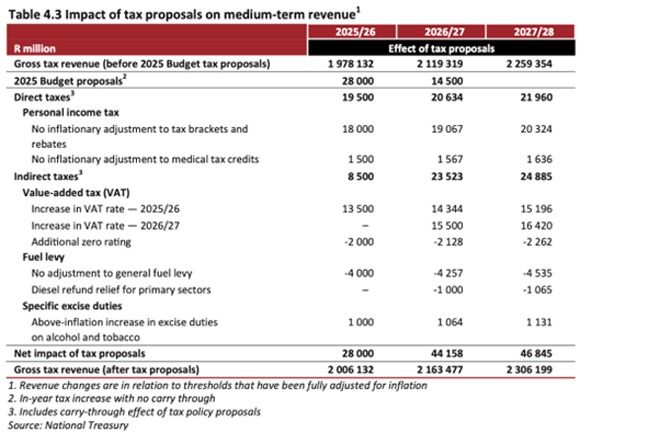

Godongwana expects to collect R13.5 billion in additional VAT revenue this year and another R15.5bn next year. The net impact of the tax proposals for the 2025/26 tax year amounts to additional revenue of R28bn and R44bn in 2026/27.

The burden

Bouwer says although the VAT blow has been softened, the relief for bracket creep that was included in the Budget tabled on 19 February has gone. This means an additional R18bn tax burden for already financially stressed South Africans.

People’s disposable income will be carved away by the higher personal income tax burden, no inflationary increase in the medical tax credits, no adjustments to the primary, secondary or tertiary rebates, higher-than-inflation sin tax increases, and again no increase in the tax-exempt amount on from local interest.

This threshold has not increased since 2013. “From a savings perspective, there seems to be a general reluctance to increase certain thresholds. Because it is gradual, we do not necessarily see the impact, but it is substantial.”

She believes the expected R13.5bn could be less because of this heavier tax burden on consumers. National Treasury’s view is that middle- and higher-income earners will bear the brunt of the VAT increase. The point is there will be less money available for spending.

“The most interesting part of the Budget will now play out in the parliamentary process,” she adds.

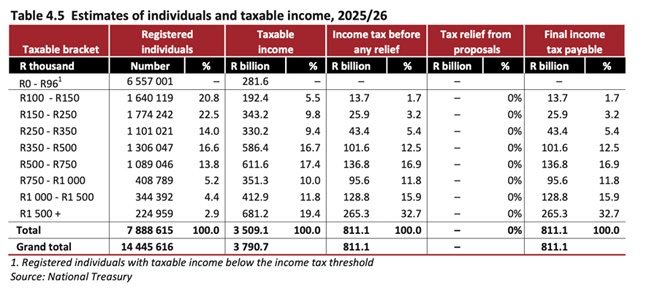

Bishop remarks that roughly 560 000 people earning R1 million or more a year pay almost half of personal income tax in South Africa. More than six million South Africans fall below the taxable threshold. This shows how “highly redistributive” the tax environment really is.

Not comparing apples with apples

Badenhorst says the Minister of Finance attempted to motivate the VAT increase by referring to the VAT rates of peer countries and comparing their rates with that of South Africa. The average of the peer countries is 19% compared to our current rate of 15%. The minister reckons this is “low” compared to the peer countries’ average.

“One cannot consider the VAT rate in isolation. Botswana has a VAT rate of 14%, but their primary healthcare and education systems are exempt for VAT purposes. Their corporate tax rate is 22% (SA: 27%), and their maximum personal income tax rate is 25% (SA: 45%),” notes Badenhorst.

Scandinavian countries’ VAT rates are 25%, and although their personal income tax rates are eye-wateringly high, virtually everything in these countries, such as education and healthcare, is free. Their corporate tax rates range between 20% and 22%.

“They have taken a policy decision to move away from direct taxes to consumption taxes. That is why their VAT rates are so high. It is therefore dangerous just to look at these rates in isolation and draw the conclusion that our VAT rate is low compared to other countries.”

Issues that are also not brought into the equation are the cost of doing business in South Africa, the cost of labour, and business unfriendly policies.

Strengthening SARS

Godongwana has allocated R7.5bn to the South African Revenue Service (SARS) to ensure increased tax compliance. SARS Commissioner Edward Kieswetter believes the tax gap amounts to about R800bn.

Read: How SARS arrives at R800bn in uncollected tax

“If there is R800bn, it could reduce the need for borrowing. It could aid with expenditure and eventually – as happened in the 2000s – lead to tax reductions, which would stimulate growth,” says Bishop.

Johnny Moloto, head of corporate affairs at BAT in sub-Saharan Africa, says it is encouraging that SARS will be strengthened. He believes a stronger SARS and better equipped law enforcement bodies to investigate and prosecute complex economic crimes could result in the recoupment of the R28bn in uncollected tobacco taxes that will be lost to the illicit trade this fiscal year.

“Eliminating the illicit tobacco trade would provide a significant revenue boost to the government and limit the need for further tax measures, such as the proposed second VAT increase of 0.5 percentage points that is pencilled in for next year, thus cushioning ordinary citizens from the tax burden.”

There is widespread recognition that high excise duties fuel the illicit market for tobacco and alcohol. The increase in excise duties this year for cigarettes and cigarette tobacco is 4.75%, and 6.75% for alcohol.

Amanda Visser is a freelance journalist who specialises in tax and has written about trade law, competition law, and regulatory issues.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies.