Retirement fund withdrawals could boost household’s disposable income this year and in 2025, but they may also contribute to higher inflation, resulting in repo rate hikes, according to research published by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) this month.

The “economic note” explores the possible macro-economic impact of the two-pot retirement system, which will be implemented on 1 September.

The two-pot system will lead to several possible economic and fiscal repercussions that are fundamentally linked to how people will react to this new source of income, say the authors, who are Nkhetheni Nesengani, Riaan Ehlers, Mish Choonoo, Annelie van Niekerk, and Theo Janse van Rensburg.

“Outcomes will vary depending on the rate of uptake of the available funds, as well as the intended destination of the funds (consumption or debt reduction). Although the reforms will help employees to access funds in the one-third pot [savings component] for consumption once a year, the two-thirds pot [retirement component] will boost retirement savings.”

Currently, withdrawals from the retirement fund system are about R360 billion a year, of which between R80bn and R100bn are because of resignations. The authors assume these annual outflows will continue over the next decade, albeit at a slower pace in each consecutive year, until the transition to the two-pot system is complete. They estimate it will take about nine to 10 years for all existing members, who will have a vested component, to leave the retirement-funding system. People who become retirement fund members for the first time from 1 September will not have a vested component and will be able to make withdrawals from the savings component only.

The authors say the retirement industry is currently in a net outflow position, with annual withdrawals exceeding annual contributions. The two-pot reforms seek to minimise the net outflow over time.

Contributions will be allocated one-third to the savings component and two-thirds to the retirement component. Members can make one withdrawal from the savings component per tax year, subject to a minimum withdrawal of R2 000. But members cannot access the retirement component, all of which must be used to buy an annuity at retirement.

Gradually, the magnitude of annual net outflow is likely to dwindle, and the industry will reach a “new steady state”, the authors say.

This new steady state is estimated to result in an outflow of about R40bn to R50bn a year in less than 10 years, which is a reduction of about R50bn compared to the current outflow levels. The withdrawal amount is therefore expected to bottom out, and either reach a flat or net positive cash flow position over time, the authors say.

However, this reduced outflow is based on the key assumption that no further seeding of the savings component occurs after year one and the savings component deters people from quitting their jobs to access their vested component.

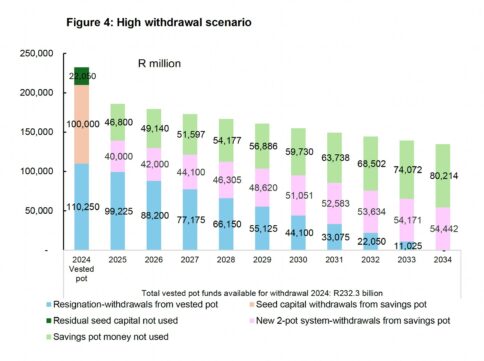

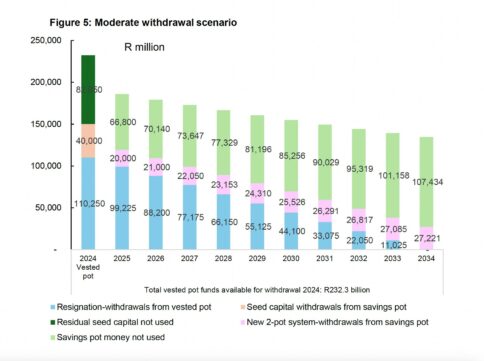

The authors present two scenarios of the macroeconomic impact of the two-pot reforms. A high-withdrawal scenario, where most fund members withdraw more than 90% of their available funds, and a moderate scenario, which they say is more plausible, where fund members make withdrawals only in financial emergencies.

High withdrawal scenario

This scenario assumes that in the fourth quarter of 2024 people will extract an additional R100bn from their savings component. This will be on top of R110bn in the 2024 calendar year that historically has been withdrawn because of resignation.

It is assumed that savings benefit withdrawals will drop to R40bn in 2025, spread evenly over the four quarters (where one-third of the total contributions for 2025 is R86.8bn), leaving R46.8bn in the savings component. These withdrawals will increase by 5% to R42bn in 2026 because of growth in the funds’ underlying investments and as contributions are subject to annual wage increases.

After accounting for taxes, household disposable income is expected to be boosted by R79bn in the fourth quarter of 2024, by R31.5bn in 2025, and by R33.1bn in 2026. Therefore, household consumption expenditure is expected to grow by an additional 0.8 percentage points in 2024, 1.8 pp in 2025 (as most of the fourth-quarter 2024 withdrawals spill over into the following year) and be almost unchanged in 2026.

Initially, the withdrawals and higher interest rates (because of rising inflation related to the rising output gap and the weaker rand following increased imports) will curtail the positive effects that the higher GDP will have on fixed investment.

As fund managers are forced to liquidate assets, thereby decreasing the pool of funds available for investments, growth in private sector fixed capital formation is expected to decline by 0.2 pp in both 2024 and 2025, before increasing by 0.1 pp in 2026 as the benefits of the two-pot system start to affect this sector.

GDP is forecast to grow by an additional 0.3 pp in 2024 and 0.7 pp in 2025. The GDP outlook returns to the pre-two-pot growth rate in 2026.

Inflation increases by 0.2 pp in 2025 and 0.3 pp in 2026, which, along with a more positive output gap, necessitates an increase in the repo rate by 60 basis points in 2025 and by 90 bp in 2026 relative to the baseline.

Higher domestic demand results in increased real import volumes, with the balance on the current account as a percentage of GDP deteriorating by 0.2 pp in 2024, 0.5 pp in 2025, and 0.4 pp in 2026.

Personal income tax (PIT) revenues increase by R41bn in 2024/25 and by R32.4bn in the year thereafter. These increases stem from the retirement fund withdrawals (as they contribute to taxable income), the expected higher employment (consumption expenditure increases in direct proportion to the additional disposable income, leading to higher GDP, with second-round effects leading to increased employment and therefore more taxable income), and higher wage settlements (through inflation expectations).

Corporate income taxes (CIT) grow by R2bn in 2024/25 and by R5.3bn in 2025/26.

Government expenditure is assumed to stay unchanged, leading to an improvement in both the primary balance to GDP ratios (0.4 pp in 2024/25 and 0.7 pp in 2025/26) and the government debt to GDP ratios (1.1 pp in 2024/25 and 2.3 pp in 2025/26).

However, there is a likelihood that households will spend a portion of their withdrawals to reduce their debt. If this portion is about 50%, the effect will reduce the impact on consumption by half, so that household consumption expenditure will increase by 0.4 pp in 2024 and by 0.9 pp in 2025. GDP will then increase by 0.2 pp in 2024 and by 0.4 pp in 2025.

Moderate withdrawal scenario

This scenario assumes that people will be more prudent and extract only an additional R40bn from their retirement funds in the fourth quarter of 2024. In 2025, savings benefit withdrawals will drop even more than in the first scenario, to only R20bn, spread evenly over the four quarters. This amount will also increase by 5% to R21bn in 2026.

Tax-adjusted household disposable income is expected to be boosted by R31.5bn in the fourth quarter of 2024, by R15.8bn in 2025, and by R16.6bn in 2026.

Household consumption expenditure will grow by an additional 0.3 pp in 2024, 0.7 pp in 2025 (as most of the fourth-quarter 2024 withdrawals spill over into the following year) and will remain relatively unchanged in 2026.

This scenario leads to smaller increases in the growth of domestic demand, resulting in smaller increases in real import volumes, and consequently the balance on the current account as percentage of GDP deteriorates by only 0.1 pp in 2024 and by 0.2 pp in both 2025 and 2026.

Growth in private sector fixed capital formation declines by 0.1 pp in 2024 and by 0.2 pp 2025, before remaining unchanged in 2026.

GDP should grow by an additional 0.1 pp in 2024 and 0.3 pp in 2025 but should stay unchanged in 2026.

Inflation increases by 0.1 pp in both 2025 and 2026, resulting in an increase in interest rates of 20 bp in 2025 and 40 bp in 2026.

If it is again assumed that the portion of withdrawals will be split in half between consumption and debt reduction, consumption will increase by only 0.17 pp in 2024 and by 0.37 pp in 2024. GDP would then increase by only 0.06 pp in 2024 and by 0.15 pp in 2025.

PIT will increase by R19.9bn in 2024/25 and by R16.3bn in 2025/26. CIT should grow by R0.8bn in 2024/25 and by R2.1bn in 2025/26.

With government expenditures also assumed to stay unchanged in this scenario, the additional revenues lead to an improvement in the primary balance to GDP ratios (0.2 pp in 2024/25 and 0.4 pp in 2025/26) and the government debt to GDP ratios (0.5 pp in 2024/25 and 1 pp in 2025/26).