South African climate experts and a leading investment management company have called on governments, businesses, and communities to increase their awareness of the pending El Niño. Besides possibly affecting the supply of food – at a local and a global level – the predicted relatively higher temperatures and lower rainfall during the next six months could push food prices significantly higher in the coming year.

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) describes the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) as one of the most important climate phenomena on Earth because of its influence on global atmospheric circulation. El Niño and La Niña are the warm and cool phases of a recurring climate pattern across the tropical Pacific – the ENSO.

Researchers in South Africa and across the globe have, through regular monitoring of the ENSO system, presented evidence that a moderate-to-strong El Niño is developing in 2023. A media release published on the CSIR’s website summarised the findings of some of these research findings presented at the El Niño 2023 Summit held at the University of Pretoria on 19 June.

The extent of this climate phenomena’s impact has varied greatly in the past. However, most previous droughts in the summer rainfall regions of the country, and seasons with a high frequency of heat waves days, are associated with El Niño events.

Dr Neville Sweijd, CSIR senior researcher and director of the Alliance for Collaboration on Climate and Earth Systems Science, said what was different and concerning this year was that published data were showing that global average sea surface temperatures had reached unprecedented levels in May and June.

“Already, records for June air temperatures are being broken in the Northern Hemisphere. This means that the El Niño is likely to be unusually strong,” Sweijd said.

Past effects of El Niño on South African agriculture

Colleagues from the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) and the South African Weather Service (SAWS) showed how previous ENSO events had affected the seasonal rainfall and temperature in the country and demonstrated the impact of the 2015/16 El Niño on agricultural production, human health, and food security, including the elevated cost of maize for human and animal consumption.

Dr Christien Engelbrecht of SAWS noted that the impact of elevated temperatures and heat waves varied across the summer months and were more prevalent in the central parts of the country. Dr Mokhele Moeletsi and Dr Johan Malherbe of ARC demonstrated that rainfall patterns and additional heat in past El Niño events resulted in crop damage and required South Africa to import maize.

Dr Peter Johnston from the University of Cape Town explained how these impacts cascade into the food economy and threaten small-scale and commercial farmers.

The experts noted that one mitigating factor is that the region has experienced good rains over the past few years, and should this occur, it might dampen the impact of drought for irrigated farming.

Incoming data: seeing the wood for the trees

On the back of this research, David Rees, senior emerging markets economist at Schroders, warns that, while leading indicators imply that food inflation in South Africa should still fall significantly in the near term, the effects of El Niño could cause it to rebound next year, leaving the South African Reserve Bank with less room to lower interest rates.

According to Rees, a key plank of the view on emerging markets (EM) is that steep declines in inflation, in part due to a reversal of food price pressures, would allow central banks to start cutting interest rates this year, brightening the outlook for economic growth in 2024.

“Incoming data have so far suggested that this view is playing out. Inflation surprise indices have fallen as CPI rates have started to decline. A reversal of energy inflation has so far done the heavy lifting, but food inflation has now clearly begun to roll over, while core price pressures are also starting to fade. Against this backdrop, falling survey measures of inflation suggest that it won’t be long until an EM easing cycle gets under way.”

Headline earnings data also suggests that El Niño does not impact global food prices. However, looking ahead, Rees says the increasing likelihood of El Niño is an emerging threat to this positive outlook.

Factors driving food prices

To understand where Rees is coming from, other factors – such as the cost of energy – that also drive food prices need to be considered. But his argument suggests that it is important to evaluate the impact of these factors in context and even remove one of them from the equation if judged necessary.

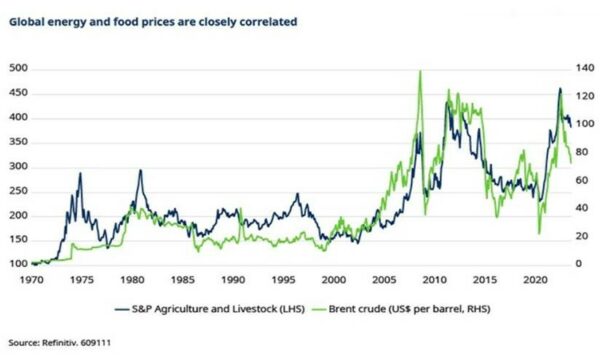

Rees explains: “Expectations for demand, along with production costs – notably energy – are equally, if not more important. This explains why there has historically been a close correlation between movements in global oil and food prices. Higher energy prices often reflect improved sentiment about future economic growth (and thus demand for food) and directly increase the cost of production in the agriculture sector. The opposite is also true for lower energy prices.

“An obvious recent example of this was seen when food prices spiked in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While higher food prices were in part due to concerns about the loss of supply of exports of wheat and other products from the region, much of the impact was due to higher energy prices as sanctions on Russian exports turned the global oil and gas market upside down. That increased the cost of producing food and forced up the prices of fertiliser. Energy prices have more recently declined, reflecting downbeat sentiment about the global economic outlook, weighing on food prices.

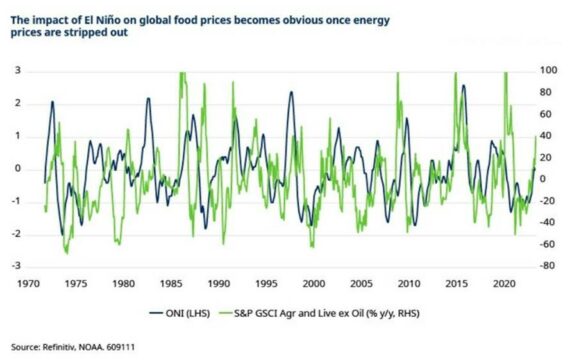

“Accordingly, it makes sense to try and eliminate the impact of changes in the cost of energy on food prices. And by doing that we find that there is a better relationship between measures of the likelihood of El Niño and movements in food prices that are not due to energy. On the face of it, this suggests that the increasing likelihood of El Niño has begun to affect food prices, and that they trade roughly in line with a ‘moderate’ weather pattern.”

Using this relationship as a guide, Rees says we can think about what might happen to food prices in the event of more severe El Niño conditions.

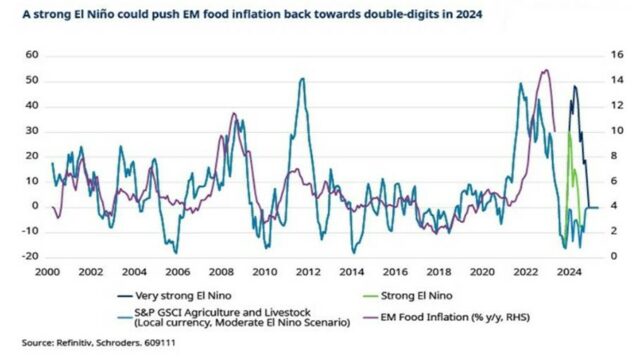

“Keeping oil prices stable, this suggests that in the event of a strong El Niño, the S&P GSCI (a benchmark for investment in the commodity markets) agriculture and livestock indeed might be around 40% higher from current levels around the turn of the year, while a very strong El Niño could lift prices by more than 50%.”

Emerging markets flood inflation: double-digit rebound predicted

Feeding these figures into Schroders’s inflation models, it seems that while a moderate El Niño would not significantly alter the outlook for inflation, anything more severe would be worrisome.

“Indeed, it is feasible that, after steep declines into year-end, average EM food inflation could quickly rebound into double digits during 2024,” Rees says.

Thus, he says – all other things being equal – higher food inflation would put a renewed squeeze on real incomes to the detriment of non-food goods and leave less room for central banks to lower interest rates.

“As such, El Niño is a stagflationary risk to EM forecasts.”

That said, Rees adds that the impact of any disruption to agricultural output and prices would be felt unevenly across EM.

“After all, poorer countries rely more heavily on agricultural output for local sustenance and economic growth. Higher food prices and shortages of goods can have a devastating impact on poorer EMs and even be the trigger for social unrest.”