Taxpayers who have been at the receiving end of an understatement penalty will most probably know how difficult it is to qualify for an exemption from this penalty.

In a recent case before the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA), the court touched on the concept of a “bona fide inadvertent error” and the imposition of an understatement penalty when a taxpayer errs but acts in good faith and unintentionally.

In the case, the Thistle Trust obtained a tax opinion on the capital gains implications of a set of distributions. It accepted the opinion and submitted its tax return based on that opinion.

The South African Revenue Service (Sars) disagreed with the position and raised an additional assessment and imposed an understatement penalty. The matter proceeded to the SCA, which held that Sars’s assessment was correct, but during the proceedings Sars made a concession in terms of the understatement penalty.

The court held that Sars conceded “correctly” that the understatement by the trust was a bona fide and inadvertent error. “Though the Thistle Trust erred, it did so in good faith and acted unintentionally,” the court held.

Bona fide and inadvertent errors

Heinrich Louw, director in the tax and exchange control practice of Cliff Dekker Hofmeyr, says, unfortunately, the court did not go into detail about the interpretation of bona fide or inadvertent error.

“This case illustrates that there is still a difference in what Sars sets out in its guide on understatement penalties and bona fide inadvertent errors and what the courts’ view may be on what the proper interpretation is.”

In terms of the Tax Administration Act, an understatement is any prejudice to Sars or the fiscus when a taxpayer does not file a tax return, omits something from the return, makes an incorrect statement, or engages in an impermissible avoidance arrangement.

“The main purpose of the understatement penalty regime is to deter unwanted behaviour that causes non-compliant reporting … To reflect this purpose, the triggers are actions or inactions that negatively affect the submission or content of returns, that is, the reporting obligations of a taxpayer,” the guide says.

Sars goes on to explain what it means by “bona fide” and “inadvertent error”. “Bona fide” is defined as “genuine” and “real” or authentic, true, actual, or legitimate. The courts have in a previous case added “with good faith” and “without intention to deceive”, but Sars seems loath to accept this.

Good or bad faith

In its guide, Sars says the courts have lost sight of the fact that an error cannot have good or bad faith and cannot have the intention to deceive. “In fact, all these definitions and synonyms must be grammatically contextualised – the trigger (actions or inactions that negatively impact the submission or content of tax returns) must be bona fide inadvertent, not the person who made it.”

Sars wants to move away from the subjective mindset of the taxpayer to a position where it is almost irrelevant whether you acted with good or bad intent, says Louw.

Sars is saying, for the taxpayer to rely on the defence of bona fide inadvertent error, it must be a genuine or real inadvertent error that did not involve any decision-making.

Sars seems to conclude that a bona fide inadvertent error can only be akin to a typo. Louw does not agree with this view, and in the Thistle Trust case, the court also did not agree with it.

The SCA appears to suggest that a taxpayer may “consciously and deliberately” adopt an opinion, complete its returns accordingly, and be regarded as having acted in good faith and unintentionally and qualify for exemption from understatement penalties, Louw says in the firm’s December Tax and Exchange Control Alert.

He adds that in this instance, the taxpayer obtained a tax opinion and believed that it was correct. However, it may be more difficult to use bona fide inadvertent error as defence in the absence of a qualifying tax opinion.

‘Mistaken belief’

Just maybe there’s an argument to be made that when a taxpayer believes his tax position is correct, and it was not unreasonable to have completed the return based on a mistaken belief, it can be considered a bona fide inadvertent error.

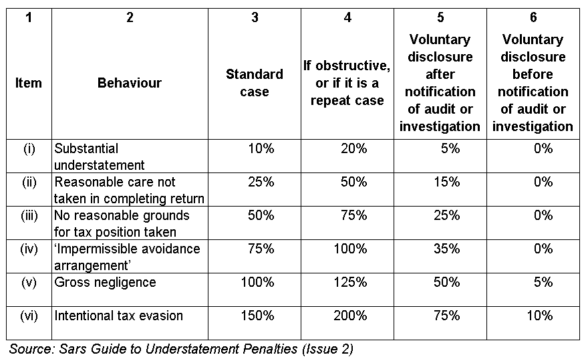

However, Louw points out that once it is established there was an understatement, the imposition of the understatement penalty is not a matter of discretion but is mandated by law. The level of the penalty will depend on the behaviour of the taxpayer.

It may also be argued that even though none of these behavioural categories is relevant, the taxpayer can fit the “standard case”.

According to the Sars guide, a standard case is where there has been a substantial understatement and where the prejudice to Sars or the fiscus exceeds the greater of 5% of the amount of tax properly chargeable or refundable, or R1 million.

There certainly are two sides to the argument, and Louw is not aware of any case that has yet decisively decided the point. Taxpayers may well use the Thistle Trust case as “persuasive authority” when arguing that they have made a bona fide inadvertent error.

“Unfortunately, I am not convinced that it creates proper legal precedent,” Louw adds.

Amanda Visser is a freelance journalist who specialises in tax and has written about trade law, competition law and regulatory issues.

Disclaimer: The information in this article does not constitute legal or financial advice.

We’re busy going through a similar issue with SARS, we completed our EMP501 on 15th March, two weeks after the tax year end.

Unfortunately, SARS’s system was not up to scratch and was unable to accept our document i.e. we were too quick for them!

When we tried to query what was happening, they were all out on strike and there was nobody available to assist.

We were then lumbered with a penalty of almost R60k for not submitting our document on time and despite numerous phone calls and dispute resolutions, SARS has not responded to us.

It Sucks.