As winter sets in, South Africans are again bracing for the potential impact of loadshedding, a looming concern that has consumers and businesses wondering how severe it will be this year.

At CN&CO’s recent InsureTalk42 webinar, Clive Hogarth, the head of retail pricing at Old Mutual Insure (OMI), warned that although Eskom seems to be in a better position than it was last year, it is going to be a very tight winter. But more on this later.

Hogarth delivered a talk on “Eskom and its impact on insurance” – or, as he termed it, “Eskom se pricing”.

Last year, South Africa faced its most severe year of loadshedding to date – about 250 000 gigawatt hours.

The worst scenarios in 2022 predicted that South Africa might endure 320 days of loadshedding. However, the country ended the year with 335 days where there was some impact of loadshedding. According to official sources, this resulted in roughly 6% of South Africa’s electricity demand going unmet, reaching a maximum of stage six.

Hogarth said this had a significant impact on the economy.

“The impact on GDP ranges anywhere from around 2% to probably up to around 5%. If we look at it from the insurance industry, we felt that impact very significantly,” he said.

Industry impact – product

Hogarth said that when he first started in the insurance industry, “power surge” was a miscellaneous add-on benefit that fell under accidental damage.

“If you ever got a claim for it, you were shocked. It now became a benefit that you were tracking at board-level meetings to understand the impact power surge has.”

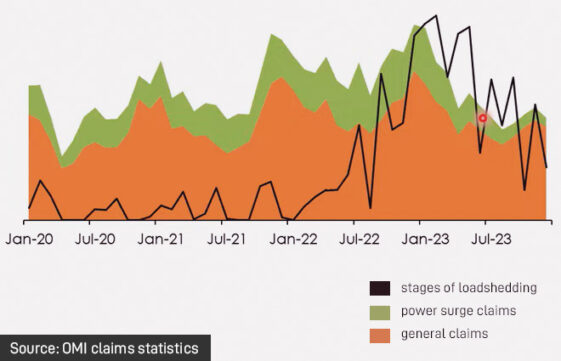

A graph that drew on data from OMI claims showed the correlation between loadshedding stages and identified power surge claims. As loadshedding escalated, both power surge claims and general claims increased, prompting heightened attention from insurance companies.

Towards the end of 2023, a notable decline in power surge and general claims was observed. Hogarth said: “That was us as an insurance company having to pay a lot more attention to the claims that were coming through.”

He said OMI was compelled to introduce product changes as power surge incidents surged.

“Simply put, a benefit that cost R1 or R2 was now costing a couple of R100 a month. So, to balance customers’ affordability needs whilst they’ll be impacted by loadshedding, we had to remove this as an automatic product benefit. It is now a separate benefit that you pay for.”

Fraud emerged as another challenge, with instances of exaggerated or false claims becoming prevalent.

“Unfortunately, people have taken advantage. Now suddenly, if your TV stopped working [due to wear and tear], you claimed it was a power surge claim,” he said.

To combat this, OMI implemented stringent processes to verify claims and deter fraudulent activities.

In addition, to qualify for certain covers, customers were required to install surge protection devices.

“We’ve also seen with customers – customers who are electing the benefit – there is an element of self-selection. Customers who opt for the benefit are more likely to experience the claims, either because they’re not powering off their devices or they live in an area where they are getting more power surge claims.”

He added there were specific areas, because of the electricity network, that were more prone to power surge claims, “with transformers and other electrical networks falling over”.

Additionally, Hogarth highlighted the indirect impact of loadshedding on road safety, with decreased visibility leading to an increase in accidents. He did point out, however, that there were challenges in accurately assessing the extent of this impact amid post-Covid adjustments.

Last, he said OMI suppliers asked for increases to cover the cost of their claims.

“They’re burning diesel. So, you go to a panel shop; they need a large generator to run their shop, or they’re having to delay because they don’t have generators, which is increasing car hire and other costs.”

Industry impact – legal

There have been growing concerns within the insurance industry about the potential for a total electricity grid failure in South Africa. Highlighting the industry’s response, Hogarth noted the implementation of certain exclusions around what is deemed a highly unlikely but catastrophic event.

He explained that reinsurers have become increasingly apprehensive and have taken the position that although improbable, there is a chance of it happening. Consequently, reinsurers have decided to withdraw coverage for total grid failure scenarios.

Hogarth said the economic impact of a total grid failure would be substantial.

One challenge, for example, is that nearly all the fuel that arrives in the Highveld comes from the coastal areas via the Transnet pipeline.