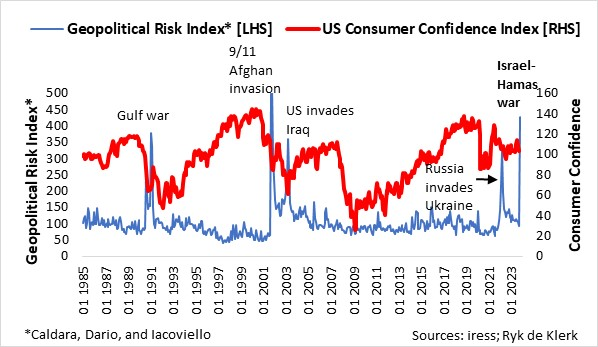

Geopolitical risk is at near-unprecedented levels because of the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War.

The Geopolitical Risk Index (Dario Caldara and Iacoviello Matteo (2021), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, working paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board, November 2021), which reflects automated text-search results of the electronic archives, has risen to levels that have occurred only four times since 1985:

- The build-up to and the onset of the Gulf War in 1990.

- 9/11 and the subsequent US-British invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

- The build-up to and onset of the US invasion of Iraq in 2002/3.

- The build-up to and onset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

With the Israel-Hamas War only a few weeks old and still developing, it is impossible to anticipate or forecast the ramifications of and fallout from the war for the global economy and financial markets.

It does, however, make sense to analyse how economies, financial markets, and central banks behaved during geopolitical crises in the recent past.

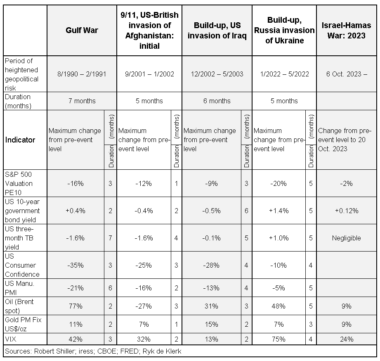

In my analysis, I looked at when the Geopolitical Risk Index started to spike – it can spike before an event as anxiety may increase because of the threat of an event, such as a war – and when it returned to more “normal” levels. By “normal”, I mean a significant fall, although the level may still be elevated compared to the average in the past.

Financial markets and central bankers adjust asset prices and monetary policies as they ascertain the consequences of or fallout from heightened geopolitical risk and/or events. In most instances, the events that gave rise to the heightened geopolitical risk persist for longer but the more the public and the markets become used to it.

Due to their prominence and size in the global context, I concentrated on the US economy and the US markets to compare the impacts of the four major geopolitical crises.

Five things in common

The time span of elevated geopolitical risk during the four said event-periods since 1985 was between five and seven months. The four periods had five things in common.

First, equity valuations, as measured by Professor Robert Shiller’s PE10 ratio metric for the S&P500 Index, fell by between 9% and 20% and bottomed within one month (9/11) and five months (Russian invasion of Ukraine), and on average three months from the pre-event levels.

Second, US consumer confidence, as measured by the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index, slumped by between 10% and 35% in the first three to four months from the pre-event levels.

Third, the gold price rose by between 7% and 15% in terms of US dollars in the first three months from pre-event levels.

Fourth, the US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index declined by up 21% in the first two to six months, and on average by about 14% from the pre-event levels.

Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, the VIX (CBOE Volatility Index for the S&P500) on average rose by about 40% in the first two to four months from the pre-event levels.

US short-term rates were already declining before the Gulf War, 9/11, and the US invasion of Iraq, and the decline extended virtually throughout the time span of elevated geopolitical risk. In contrast, short-term rates bottomed before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and moved significantly higher because of quantitative tightening by the US Federal Reserve.

US long-term government bond yields edged higher during the Gulf War in the first two months, dropped slightly after 9/11, and eased slightly with the US invasion of Iraq. Yields moved higher even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rose sharply thereafter on quantitative tightening.

9/11 followed by the invasion of Afghanistan saw a massive drop in the oil price, perhaps because there was no real threat to global oil supplies. The build-up to and the onset of the other three major geopolitical crises saw the oil price surge by between 31% and 77% in the first two to five months from pre-event levels.

Indicators reflect extreme levels of risk

Risk premium indicators have already started to reflect the current extreme levels of geopolitical risk in earnest. By the close last Friday, the prices of gold and oil (Brent spot) in terms of US dollars are both up by more than 9% from Friday, 6 October (the day before Hamas’s brutal invasion of Israel), while the VIX jumped by more than 24% over the same period.

In sharp contrast, global equities are holding their ground. Both developed-market equities and US equities, as measured by the MSCI World Index and S&P500, have lost a mere 2% since the invasion. Emerging markets also held up well, with the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (US$) down by 1.2%.

Long-term global government bond yields have also been steady since the invasion, with the US 10-year government bond yield up slightly.

The world is facing a major confidence crisis.

The longer the Israel-Hamas War lasts while tensions in the Middle East increase, the longer geopolitical risk will remain at extremely high levels.

Global economic data and company financials up to the Israel-Hamas War are likely to have little bearing on fiscal and monetary policies going forward. I think the rest of the world is aghast with what happened and could happen going forward. The future is at risk. No doubt, it will be reflected in sharply lower consumer and business confidence in the coming months.

Risk premiums are susceptible to further spikes in tensions in the Middle East and at some stage they will be reflected in the devaluation of risk assets. Furthermore, company profit and earnings forecasts are likely to be adjusted downwards as concerns about supply chain disruptions and future consumer spending are likely to become prominent. The drawdown in valuation (fall in prices) could be between 9% and 16% and could happen within the next few weeks or three months if history repeats itself.

The Israel-Hamas War could also be the maximum inflection point for the US Federal Reserve and other central banks, as falling business and consumer confidence is likely to move their monetary policies to a neutral stance from quantitative tightening. Yes, recessionary conditions are brought forward by the event.

US 10-year government bond yields and global bond yields could therefore peak sooner than later.

The heightened geopolitical risk phase or crisis will, no doubt, have serious investment portfolio and strategy implications, and I had to re-affirm my risk budget (how much I am prepared to lose). The positive, however, is that major selloffs of risk assets at some point create great opportunities too.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.