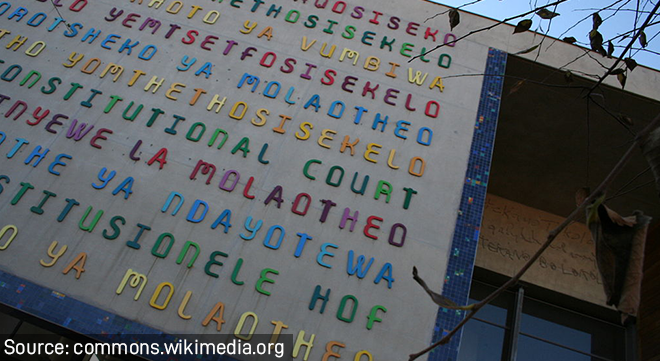

In a blow to foreign law graduates who have lived, studied and completed articles and pupilage in South Africa, the Constitutional Court has ruled that a section of the Legal Practice Act (LPA) that allows only South Africans or permanent residents to be admitted as lawyers is constitutional.

The application was brought by Lesotho and Zimbabwean graduates and consolidated at one hearing. They were supported by the Asylum Seeker, Refugee and Migrant Coalition (ASRM), Scalabrini Centre of Cape Town, International Commission of Jurists, and the Pan-African Bar Association of South Africa.

The Legal Practice Council and the ministers of Home Affairs, Labour, and Trade, Industry and Competition, all opposed the application.

In an unanimous judgment on Tuesday, the court ruled that the relevant section of the LPA passed constitutional muster.

The court also overturned a previous ruling by the High Court in Bloemfontein which had declared the Act invalid to the extent that it did not allow foreigners to be admitted as “non-practising” legal practitioners – that is, as legal advisers with no rights to appear in court.

The applicants all argued that the Act was discriminatory. They had all lived in South Africa legally, had completed their degrees at local universities and completed their articles at local firms. They argued that the citizenship/permanent resident requirement was an “absolute and inflexible barrier”. It was “unreasonable, irrational and unjustifiable” and was unique to the legal profession.

The ministers argued that the Act was in line with the government’s obligations to ensure that foreign nationals did not circumvent immigration and labour laws.

The regulation of the legal profession was in the public interest and the applicants had failed to establish that they were a “vulnerable group”, such as refugees.

The practice of law was also not a rare or critical skill that justified a special dispensation.

Judge Zukisa Tshiqi, who penned the ruling, said the complaint was not that a sovereign state had no power to pass laws regulating a certain profession or trade.

“The complaint seems to be rather focused on whether, in doing so, the state has acted in an objectively rational manner … related to a legitimate governmental purpose.”

Judge Tshiqi said non-citizens had no rights under section 22 of the Constitution (which entrenches the rights of citizens to choose their trade occupation and profession). The legislature could decide how far to extend admission into the legal profession to non-citizens, and it had chosen to draw the line at permanent residents.

“That does not mean that in doing so, it is at liberty to act in any way it chooses. If, for example, the legislature allowed all non-citizens to be admitted as legal practitioners, save for Japanese citizens, that would be prima facie arbitrary and unlikely to serve any legitimate governmental purpose,” Judge Tshiqi said.

Addressing submissions that there was no rational basis to differentiate between permanent residents and the applicants and refugees and asylum seekers, the judge said, “The rationale for accepting permanent residents is that they have been granted a right to live and work in the country on a permanent basis subject to the country’s immigration laws. The same cannot be said for non-citizens who are refugees or who are on study or work visas.”

Judge Tshiqi said the differentiation was there to protect opportunities for South Africans, and that was permissible.

She said when foreign nationals chose to study and do vocational training in South Africa, “they made this choice fully conversant with the fact that they are not eligible for admission, or at the very least, they ought to be conversant”.

The “discrimination” in the Act was not unfair.

“Their employability in different capacities that do not require admission as a legal practitioner is not curtailed … They are therefore not left destitute,” she said.

ASRM founder Muchengeti Hwacha said, “We are disappointed in the outcome, but we obviously respect the decision of the court.”

This article was first published by GroundUp and is republished with permission in terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence.