Research by the Actuarial Society of South Africa (ASSA) highlights why it is important for pensioners with a living annuity to meet regularly with their financial advisers to review their drawdown rates.

The results of the research should be carefully considered by living annuitants who assume they can ensure their capital will last the distance simply by setting a low initial drawdown rate – and hoping for the best.

“A living annuity is not a set-and-forget product,” said Andrew Davison, the chairman of ASSA’s Investments Committee. “The management of a living annuity needs to be dynamic. Drawdown rates and investment strategies may need tweaking over time, taking into account the age, gender, and circumstances of the pensioner and their spouse, as well as the economic environment.”

To highlight the challenges involved in managing living annuities, Davison recreated the outcomes of living annuities for 75 hypothetical pensioners.

The assumptions

Davison’s objective was to compare identical strategies applied during different market conditions, to understand the impact of market returns and the fluctuations of those returns on outcomes.

The assumptions were the same for all 75 living annuities, except that the pensioners retired on different dates. The first retired in January 1957, with another retiring every six months thereafter until 1994, allowing for a 30-year period until the end of 2023.

All 75 pensioners had a retirement horizon of 30 years and bought their living annuity with retirement capital of R1 million.

The 75 pensioners had the same income strategy of drawing an income of 5.7% at the start, increasing by inflation every year. Living annuities allow clients to select an income level between 2.5% and 17.5% annually.

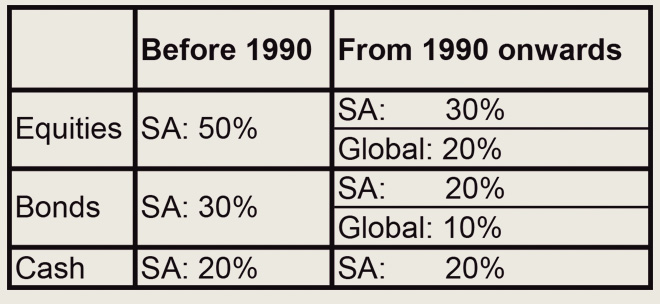

The pensioners were also assumed to have applied comparable, diversified investment strategies to the underlying investment portfolios.

Davison’s dataset for global asset classes began in 1990, so the investment strategy assumed before that was 100% exposure to domestic South African asset classes. However, the overall allocation to equities, bonds, and cash was consistent throughout.

The outcomes were based on the actual returns for each asset class and actual inflation (CPI). Annual fees of 1% were factored in, but it must be noted that returns and fees will vary considerably in real life depending on individual circumstances.

The outcomes

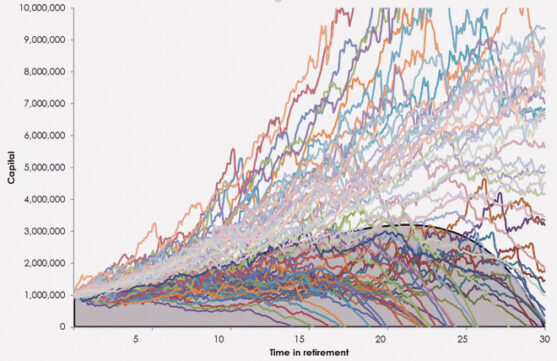

Davison said the impact of the fluctuating market conditions on the underlying investment portfolios resulted in 32 out of the 75 living annuities running out of capital within the 30-year period.

“This is a high failure rate. If the pensioners concerned happened to have lived a long time, there was a high probability that they were left destitute unless they had other sources of income.”

After only 20 years, the capital in nine of the 75 living annuities had already been depleted, with about half of the living annuities left with less than 50% of the original capital in real terms. The earliest depleted case was recorded after only 13 years.

The graph below represents the different retirement outcomes.

“The assumed drawdown of 5.7% at the start, with CPI increases each year, is the level that ensures that the capital lasts for precisely 30 years using the average return from the assumed investment strategy. This ‘average’ scenario is shown by the grey-shaded area behind the spaghetti of lines on the graph. Given that the drawdown and investment strategies were similar, the extreme range of actual outcomes is quite astounding,” Davison said.

The need for regular re-assessment

Davison said the reality that 32 out of the 75 living annuities ran out of capital within the 30-year retirement horizon despite starting with a reasonably sensible drawdown rate of only 5.7% and having a diversified, balanced investment strategy supports the need for regular re-assessment of both the investment portfolio and the drawdown rate.

“If the timing of your retirement places you on a less than favourable investment path, you want to recognise it and do something about it before it is too late.

“The unknown of how long you might live and hence the risk of depleting your assets prematurely means that living annuities need careful management and a prudent approach to the level of income withdrawn as a monthly pension.”

Unfortunately, it appears that many pensioners are not regularly reviewing their drawdown rates, he said. This probably means these pensioners do not regularly meet with their financial advisers to review underlying investment portfolios.

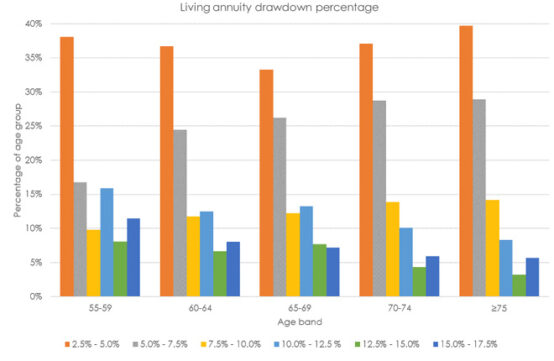

Davison conducted a deep dive into the living annuity statistics released by the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa in November last year.

Somewhat surprisingly, the proportion of pensioners aged 75 and over in the lowest drawdown band of between 2.5% and 5% was greater than all the younger age bands. Similarly, the oldest group of pensioners had the fewest cases drawing above 15%.

Given the common lament that most pensioners are drawing too much from living annuities, this sounds like good news, he said.

However, as pensioners get older, their expected time horizon reduces, which means they can afford to increase their percentage drawdown without affecting the sustainability of capital.

“There will be some pensioners for whom the bequest motive outweighs their need to fund their own living costs, but this pattern in the data seems to indicate a certain inertia about decisions to change parameters on financial products.”

According to Davison, setting a percentage that is never reviewed is not likely to result in a stable income in real terms. It also means some older pensioners may be scraping by, yet their capital could support a higher income.

“If there is a tendency not to review and adjust drawdown rates, it is safe to assume that many pensioners are also not meeting with their financial advisers to assess the composition of the underlying investment portfolio,” Davison said.

Winning the living annuity race

Instead of selecting a low drawdown rate when investing in a living annuity and then hoping for the best, a more appropriate strategy is to set a conservative drawdown percentage at the start of retirement and then gradually increase the pension amount by inflation, Davison said.

At the same time, you need to keep an eye on what percentage of assets that translates to and, together with your financial adviser, make adjustments if necessary.

“Using mortality, investment return, and inflation assumptions, we modelled that a 65-year-old single male should aim for a sustainable drawdown percentage of around 4.5% with a moderate balanced investment strategy. The same pensioner 15 years later at age 80 can afford a much higher drawdown percentage of 10.5% with a similarly low chance of running out of money,” he said.