South Africa is set to receive a post-election dividend soon. The table is laid for the first credit rating upgrade since June 2009. The new wave of optimism and anticipation created by the Government of National Unity (GNU) was underscored by last week’s 2024 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS), which ticked all the boxes of fiscal and monetary discipline.

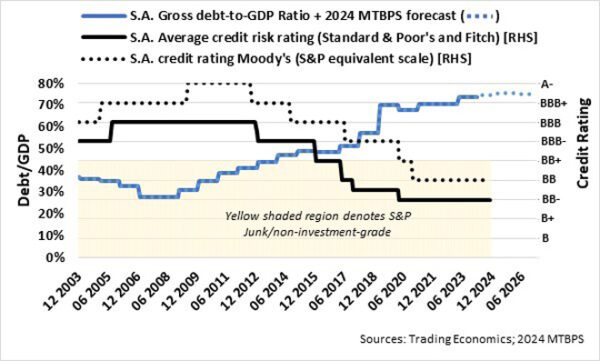

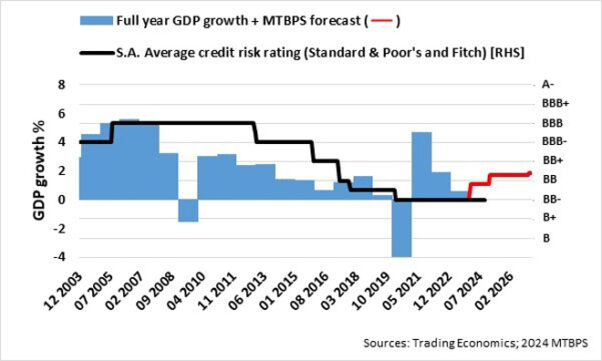

South Africa’s credit worthiness, as measured by the country’s credit ratings, deteriorated sharply over the past decade because of a myriad of factors, including state capture, corruption, broken state-owned enterprises, and dismal economic growth. Over the past 12 years, South Africa’s gross government debt-to-GDP ratio increased to about 75% from 41%, while economic growth slipped to less than 1% from 2.4% over the same period.

From the MTBPS forecasts, it is evident that the government is budgeting to rein in borrowing, and the debt-to-GDP ratio has reached a plateau.

I think the faster economic growth forecast in the MTBPS is far more convincing for the credit rating agencies and local and global investors than in the past, particularly with the government and the private sector working together amid fiscal and monetary discipline.

Yes, South Africa is due for a credit rating upgrade. But what does it mean for South Africa’s financial markets?

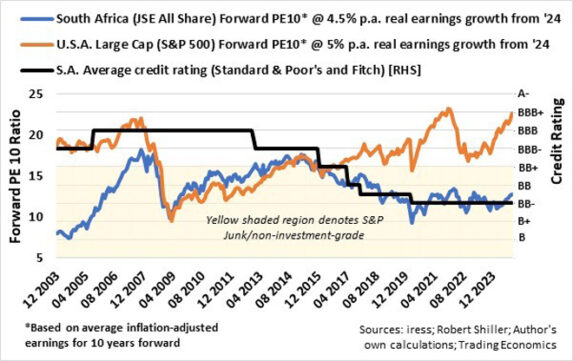

Equities

My preferred yardstick to value stock markets is the forward PE 10 ratio (FPE10), which I calculate by dividing the real price by the average inflation-adjusted earnings 10 years forward. The main difference between the FPE10 and the Robert Shiller PE10 metric is that the average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years are used in the latter metric. Both metrics look through short-term impacts on earnings, such as big market-moving economic events and cycles. I assumed that the JSE’s real earnings growth would average 4.5% a year over the next 10 years – the same as in the past five years, and the S&P 500’s earnings growth of 5%.

From 2003 to mid-2008, the South African equity market (measured by the FPE10 of the FTSE/JSE All Share Index) re-rated by more than 130% compared to US large-cap stocks (S&P 500 index) as the valuation gap closed as emerging markets shone on the back of China’s rise in the modern world with “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history” (World Bank).

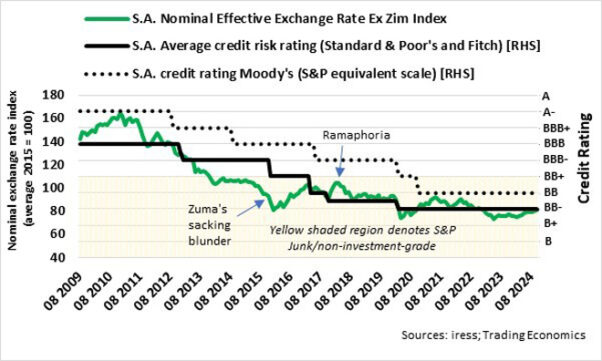

Thereafter, South Africa’s rating closely followed that of the S&P 500 until Jacob Zuma’s sacking blunder in December 2015 when he fired two finance ministers in a week. The sacking resulted in an immediate cut in the credit rating to BB+ or generally a junk rating by rating agencies S&P and Fitch, followed by successive cuts by Moody’s in March and May the following year. Since then, the FTSE/JSE All Share Index’s FPE10 has tracked the down-trend in South Africa’s credit rating. South Africa’s credit rating (average of S&P and Fitch) stabilised at BB minus since 2020, while the FPE10 moved in a range of between 10 and 13 and is currently near the top of the range.

A one-notch upgrade in South Africa’s credit rating to BB is likely to lead to a higher FPE10 and therefore a re-rating of the FTSE/JSE All Share Index despite the country’s debt still being rated as junk. Further rating upgrades over the next two years could see the South African stock market outpacing its peers (emerging markets) and performing solidly against developed markets. Yes, the valuation gaps may narrow in favour of South Africa.

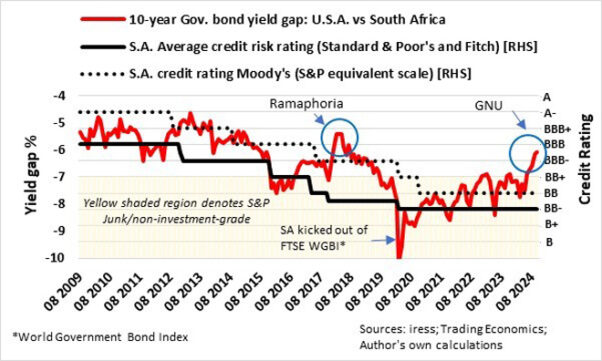

Bonds

The 10-year government bond yield gap between the US and South Africa ranged between minus 4.5% and minus 6.5% from 2009 to November 2015 when South African government bonds had an investment grade. Zuma’s sacking blunder in December 2015 and the immediate rating cuts by Fitch and S&P saw the bond yield gap widening as South African bonds were sold off. South African bonds, however, recovered as Moody’s, the other rating agency, kept South Africa at investment grade.

The short-lived Ramaphoria following the election of Cyril Ramaphosa as the president in February 2018 initially led to a wave of optimism, locally and globally, and faded spectacularly shortly thereafter, briefly narrowing the yield gap to about minus 5% despite further downgrades by all three rating agencies. Moody’s downgrade of South African debt to junk status (Ba1) in March 2020 resulted in a massive sell-off of South Africa bonds as South Africa was kicked out of the FTSE World Government Bond Index.

Since 2021, the bond yield gap ranged between minus 7% and minus 8.5%. The yield gap has narrowed to minus 6% since the GNU was formed after the May elections. Although credit rating upgrades will underscore the current bond yield gap, a further narrowing to minus 5% or even minus 4% will be tough and could turn out to be speculative because it will need Moody’s to upgrade South Africa by more than one notch to get to investment grade and therefore inclusion in the FTSE World Government Bond Index.

The rand

The nominal effective exchange rate of the rand, which measures the external value of the currency against that of a weighted basket of South Africa’s largest trading partner countries, tends to track South Africa’s credit ratings.

The effective rand traded in a range of between 73 and 87 since May 2020 and is currently in the middle of the range. From the accompanying graph, it is evident that a credit rating upgrade is likely to exert upward pressure on the rand.

Conclusion

I think a credit rating upgrade for South Africa’s sovereign debt is on the cards sooner than later. According to reports, S&P’s rating for South Africa is due in mid-November, while an upgrade by Fitch and Moody’s will probably follow 2025’s Budget speech. I do not think the credit rating upgrade will be pushed to investment grade yet, though. But at least it is a starting point.

The credit rating upgrade is likely to have profound implications for investment portfolios because the rand values of non-rand-denominated investments are vulnerable to the stronger external value of the rand. Yes, South African assets are turning the corner for the better and could significantly re-rate against other emerging and developed markets if the country regains an investment grade rating by Moody’s and is thereby included in the FTSE World Government Bond Index. The main proviso, however, is that the GNU holds together.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.