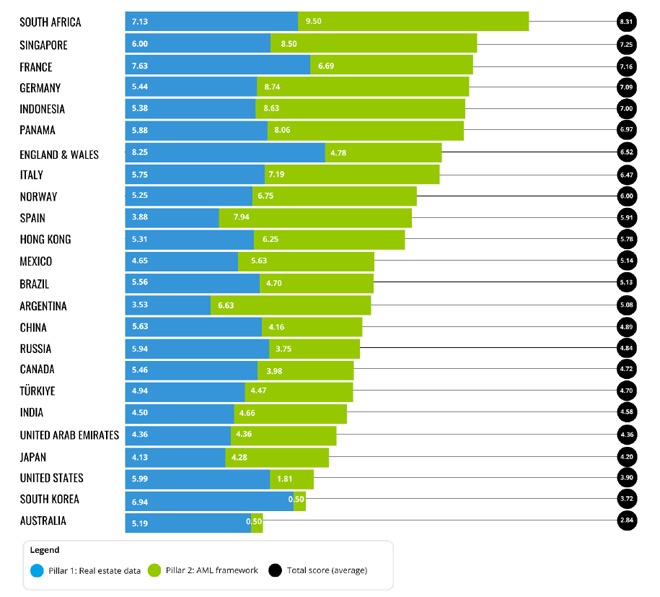

South Africa achieved the highest score among 24 countries in an index that evaluates how well a real estate market is protected from illicit financial activities, particularly money laundering.

The findings of the first Opacity in Real Estate Ownership (OREO) Index were published last week. The tool was developed by Transparency International and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective (ACDC).

Transparency International is a global non-governmental organisation dedicated to combating corruption. Founded in 1993, it operates in more than 100 countries, focusing on promoting transparency, accountability, and integrity in governance, business, and civil society.

The ACDC is an initiative that brings together a diverse group of experts – including investigative journalists, data scientists, academics, and policy advocates – to combat transnational corruption. Launched in 2020, the ACDC focuses on exposing the mechanisms and flows of illicit financial activities, particularly in high-risk sectors such as real estate and private investment funds.

The OREO Index evaluates the ideal framework to protect real estate markets from dirty money, using two pillars:

- Availability and adequacy of real estate data: This pillar examines whether sufficient and reliable data about property ownership is accessible, which is crucial for tracking and preventing illicit transactions.

- Coverage and scope of an anti-money laundering (AML) legal framework: This pillar evaluates the strength and comprehensiveness of laws and regulations designed to combat money laundering within the real estate sector.

Each pillar is composed of three and four components respectively, each receiving a score from 0 to 10. A weighted average is used to calculate the two pillars, which contribute equally to the final score. The overall OREO Index score is determined by averaging these pillars.

The 24 jurisdictions assessed were the 18 members of the G20, plus Hong Kong, Norway, Panama, Singapore, Spain, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The report found that all the jurisdictions have gaps in their AML frameworks. In most of the jurisdictions, a would-be money launderer investing in real estate could evade detection by taking advantage of “wide-open loopholes” in AML regulation.

In additional, the ability of media, civil society, and government agencies to detect cases of suspicious real estate ownership and uncover gaps in implementation is severely impaired by sub-standard data systems in all the jurisdictions assessed.

Assessment of South Africa

South Africa, followed by Singapore and France, was the best performer overall. However, the report says significant gaps remain even in well-performing countries.

Australia, South Korea, and the United States were among the worst-performing countries, largely because AML regulation for professionals involved in real estate transactions is lacking.

The results of the survey indicate that reforms by Panama, South Africa, and the UAE – primarily in response to scrutiny by the Financial Action Task Force and their inclusion on its grey list – have improved their legal frameworks. However, these improvements are not yet sufficient.

Some of the AML rules were adopted by South Africa fairly recently, and it remains to be seen whether the measures will be implemented and enforced meaningfully, the report says.

The survey found that most countries place at least some AML obligations on professionals in the real estate sector. But South Africa is one of only four countries that ensure real estate transactions are subject to scrutiny – at least on paper – by professionals who are sufficiently covered by AML regulations. The other three are Germany, Singapore, and Spain.

South Africa’s centralised property register captures comprehensive records on real estate transactions, from date and price of purchase to historical ownership and purchase data. However, the register cannot be consulted for free and appears to accept applications for access from South African citizens only, creating a hurdle for those seeking to follow illicit wealth from other countries into South African real estate.

Almost all the jurisdictions assessed require the collection and verification of some kind of beneficial ownership information for legal entities purchasing real estate. In most countries, real estate professionals are prohibited from proceeding with transactions if the beneficial owner cannot be determined.

However, of the 22 jurisdictions that cover professionals in their AML laws, at least 13, including South Africa, permit professionals to rely on senior officers or directors as substitutes if the true beneficial owner remains undisclosed, a practice that easily obscures the real owner. As a result, professionals can default to identifying directors, leaving the true ownership concealed and opening the door to abuse, the report says.

The study makes the case that easy access to open data on real estate transactions, as well as reference datasets including beneficial ownership, corporate and land registries, is essential for allowing authorities and public-interest researchers to detect cases of money laundering and monitor the effectiveness of policies. At present, however, the jurisdictions assessed are falling far short of the standard.

“We have known for a long time that real estate is a magnet for dirty money. And yet, the OREO Index shows that countries, including those that have recently reformed their systems, still have major gaps in their systems. It is no wonder that real estate markets are bursting with dirty cash, making cities around the world unaffordable,” said Maira Martini, the chief executive of Transparency International.

“While progress has been slow, the OREO Index also shows that international anti-money laundering standards can have an impact. We urge standard-setter bodies such as the Financial Action Task Force and global fora such as the G20 to develop new policies and guidelines to help countries address remaining loopholes.”

What about a country such as Switzerland?