Every month a minimum debit order comes off your bank account to whittle down your mortgage bond. If you are diligent and do not access the bond, you should typically pay it off after 20 years.

However, many ask what to do with savings available after all expenses have been met. Should you invest these savings into the stock market or try to pay down your debt quicker? This article explores how your wealth would have changed over the past 20 years if you had implemented various strategies.

It is June 2002, and you buy a house for R1.1 million. You put down a deposit of R100 000 and get a bond for R1m at a rate of prime less 1%. The average prime rate was 15.75% for your first year. Thus, your rate was 14.75%, and your starting net asset value (NAV; assets less liabilities) would have been R100 000.

Your first-year payment to the bank would have been R157 000, or R13 000 a month. Almost all of that amount would have gone to servicing interest, and thus very little capital would have been paid back.

You have also been disciplined that year, and you were able to save R1 000 a month (R12 000 for the year), and you now have a choice to pay back your loan or invest it in the stock market.

In this analysis, your options are either the FTSE/JSE All Share Index (Alsi) or the US S&P 500 Index. Let us also assume that you were able to increase that saving each year by inflation; therefore, R12 000 in the first year, R12 144 in the second year, and so on.

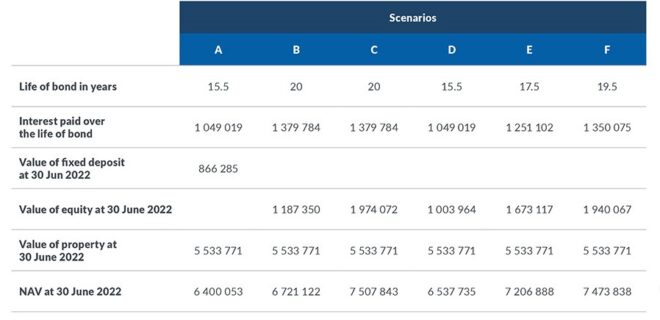

Let us look at various scenarios and how they would have impacted your wealth 20 years later.

Scenario A: Pay off your bond as quickly as possible, and after paying down the debt, invest in a fixed deposit

This is the most conservative approach, as you put all your savings into your bond and shy away from markets. Remember, you are not investing in anything; you pay down your debt a little more each year. But you also save all the future interest on that amount paid back, which compounds in your favour.

You were charged a whopping R147 000 in interest in your first year, and your loan closes at only R990 000 – a measly R10 000 less than how you started that year. You now use your R12 000 in savings to reduce your debt to R978 000. So, you are chipping away at your debt as best you can. Fortunately, your property has increased in value to R1.17m, and thus your NAV is now R192 000.

If you continue putting your inflation-growing savings into the loan, you will pay off your loan in 15.5 years instead of 20.

Now that you have paid off your debt, you decide, being conservative, to save all the funds that you would have paid into the bond (monthly bond payments plus extra savings) into a fixed deposit. Thus, 4.5 years later, after 20 years, you would have a house worth R5.5m, a fixed deposit of R866 000, no debt and a NAV of R6.4m.

Scenario B: Do not pay down your bond at all but invest in the JSE

Instead of paying off your bond as soon as possible, you decide to put your savings into the Alsi, and all the dividends are reinvested in that portfolio over time. Therefore, your bond will last the full 20-year term, and you will pay the maximum possible interest on this debt. However, after 20 years, you will have an equity portfolio worth R1.1m and a paid-off house. Thus, your ending wealth would be R6.7m.

Scenario C: Do not pay down your bond but invest in the S&P 500

This scenario is similar to Scenario B, where you do not pay off your bond but invest the money in the S&P 500, as you believe better returns will be generated offshore.

In rand terms, you would have had a very similar investment path until about year 15, when you would have begun to pull ahead, as the South African market underperformed the US. At the end of 20 years, you would have an offshore equity portfolio worth R1.9m, giving you a total NAV of about R7.5m.

So far, investing in the stock market was a better decision than paying off your debt. But let us explore two more variations to the above.

Scenario D: Pay down your debt as soon as possible and then invest in the S&P 500

This is similar to Scenario A, where you try to pay off your debt as soon as possible, but instead of investing in a fixed deposit after you have paid off your bond, you invest in the S&P 500. In this scenario, you will also pay off your debt after 15.5 years, but you would have invested in the stock market for only the past 4.5 years. Thus, you have not received the benefit of time and compounding in the stock market, but you would have at least beaten Scenario A and ended with a NAV of R6.53m.

Scenario E: Investing in the S&P 500 when cheap or paying off your debt when expensive

This is the most interesting scenario where you put a little more thought into what you do. In this scenario, you invest in the market when it is cheap or pay back your loan when it is expensive. Then, if the market is about average, you split your savings between the two.

In this scenario, you would have invested your savings into the market for six of the 20 years. You would have paid off your bond in four of the 20 years and split your savings the rest of the time. In Scenario E, you would have paid back your loan after 17.5 years, and after it is paid off, you then put all your proceeds into the S&P 500. After 20 years, you would have an equity portfolio of R1.6mn, giving you a closing NAV of about R7.2m, or second place after Scenario C.

Conclusion

The best scenario is C, investing as much as possible in the S&P 500 and allowing for compound growth over the long term. Scenario A has the worst outcome. The interest saved on paying off your bond and the interest earned afterwards is not as good as being invested in the market. And, if we deduct income tax on that interest you earned, the final NAV would be even worse.

Intuitively, you would think that Scenario E is the best strategy, as it uses a lot more brain power, but it does not beat Scenario C because of the times you split your savings between bond payments and the market. This is because the market can be averagely valued, but because the earnings of the underlying companies continue to rise, it ends up beating the interest rate on your bond over time.

For those who have read this far and love the numbers, we have included a slight variation to Scenario C in Scenario F, where we continually invest in the stock market unless it is expensive. Now we are saying that we are long-term investors all the time except when the market is expensive. Yet, we still do not beat Scenario C.

So, it is clear that trying to time the market around cheap or expensive is not a successful long-term strategy. You would be much better off putting a debit order in your bank account to invest in the market no matter what and allow for long-term compounding over and above the interest paid or earned.

Ross McConnochie (CFA) is an offshore analyst and portfolio manager.

This article was first published by Anchor Capital is republished with permission.

Disclaimer: This article is published for informational purposes and does not constitute financial advice.

Interesting, but there are 2 major flaws in the argument. Firstly, the article considers only returns, but ignores risk altogether. So scenario C (putting all the savings into the S&P 500) gives a slightly better return than Scenario D and a very slightly better return than Scenario E, for that particular period, at the expense of a very much higher risk. Scenario A is completely risk free (except for the slight risk of a large rise in bond interest rates during the first year or two) while scenario D is similarly risk free for the the first 15.5 yrs and then low risk. The second flaw is that it considers only one particular period (June 2002 to June 2022). The results would probably be different if another 20 year period was chosen.