Those for and against some form of basic income grant (BIG) continue to produce research to support their respective causes. The most recent document to come to my attention are the results of a survey by Afrobarometer and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, a non-governmental organisation and think tank, which is in favour of a BIG.

The survey asked South Africans about their attitudes towards various aspects of taxation.

One of the statements put to participants was: “It is fair to tax rich people at a higher rate than ordinary people in order to help pay for government programmes to benefit the poor.”

Nearly two-thirds of respondents – 64% to be precise – agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, whereas 27% disagreed or strongly disagreed. (9% neither agreed nor disagreed, or didn’t know, or refused to answer.)

There is no indication in the published results what is meant by “rich people”, “ordinary people”, and “the poor”. What participants understood by “government programmes” is also not explained.

The researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with 1 600 adult South Africans in May and June 2021. The results were published in March this year.

The responses to some of the statements that were put to the participants are broken down by age, gender, education, whether the person lives in an urban or a rural area, and where the person falls on Afrobarometer’s Lived Poverty Index, “which measures respondents’ levels of material deprivation by asking how often they or their families went without basic necessities during the preceding year”.

But the responses are not differentiated according to whether the participants are registered for personal income tax (PIT), or whether they were assessed for PIT in the most recent tax year.

Who pays personal income tax?

PIT is the government’s largest source of tax revenue, contributing 35.5% of the total tax revenue collected in 2021/22.

The adult (over the age of 18) population of South Africa is between 39 million and 40 million people. How many are liable for PIT?

In March, National Treasury and the South African Revenue Service (Sars) published the 2022 edition of the Tax Statistics, which provides an overview of tax revenue collections and tax return information for the 2018 to the 2022 tax years, as well as the 2017/18 to the 2021/22 fiscal years.

By 31 March 2021, 23.9 million individuals were on Sars’s PIT register, although most of these people are not eligible to pay tax in a tax year.

According to National Treasury, it is estimated that in the 2020/21 year, 6 822 326 individuals received taxable income below the minimum income tax threshold, while 7 146 434 received taxable income above the threshold.

The implication is that some 18% of adult South Africans were liable for PIT, or 12% of the total population of about 60.255 million.

By contrast, according to President Cyril Ramaphosa, 29 million people (48% of the population) are on state welfare: 18 million receive old age, child support and disability grants, and 11 million receive the Social Relief of Distress grant.

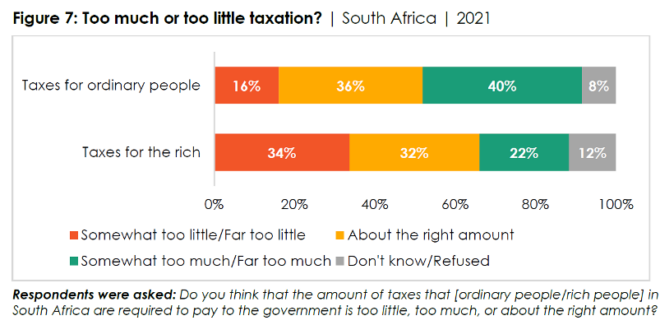

In view of the relatively low number of South African who pay PIT, should we be surprised that most of the survey’s participants were in favour of higher taxes on “the rich”, or that 34% thought “the rich” were paying “somewhat too little” or “far too little” tax?

More taxes for more services

Despite the enthusiasm for (nearly) everyone paying their “fair share”, 55% disagreed/strongly disagreed with the following statement: “Government should make sure small traders and other people working in the informal sector pay taxes on their businesses.”

The survey did not ask respondents whether they favoured the government increasing taxes to fund a BIG.

The following statements were put to participants:

- “It is better to pay higher taxes if it means that there will be more services provided by government.” 55% agreed/strongly agreed.

- “It is better to pay lower taxes, even if it means there will be fewer services provided by government.” 40% agreed/strongly agreed.

- “If the government decided to make people pay more taxes in order to support programmes to help young people, would you support this decision or oppose it?” 70% somewhat or strongly supported this statement.

It is not clear what is meant by “taxes”. Does this include value-added tax, as well as PIT, along with capital gains tax, dividends tax, transfer duty, estate duty, and donations tax?

Interestingly, support for “higher taxes and more services” was lowest among those with “high lived poverty” (47%), compared with those with “no lived poverty” (57%). Support also increased by education level: 46% among those with no formal education, rising to 59% among those with post-secondary education.

The support for higher taxes for more services may also be because 53% agreed that the government “usually uses the tax revenues it collects for the well-being of citizens”. (31% disagreed or strongly disagreed.)

Perceptions of corruption

Although 65% of respondents agreed that the tax authorities always have the right to make people pay taxes, 33% believed that most or all tax officials were involved in corruption.

However, tax officials fared better than other formal public institutions, such as the police (55% most/all corrupt), the Office of the Presidency (53%), Members of Parliament (51%), local government councillors (50%), civil servants (42%), and judges and magistrates (36%).

Despite more than half believing the Presidency (53%) was involved in corruption, only 50% of respondents said that Parliament should ensure the president accounts for how taxpayer money is spent. On the other hand,47% agreed or strongly agreed with the following statement: “The president should be able to devote his full attention to developing the country rather than wasting time justifying his actions.”

The survey commented: “The surprisingly low demand for parliamentary oversight might be linked to South Africans’ low levels of trust in Parliament as an institution and the perception that many MPs are involved in corruption themselves.”

As noted above, the survey was conducted in May and June 2021. One wonders how people would respond to similar statements about taxation in 2023, following the July 2021 riots, the publication of the Zondo Commission’s reports, Phala Phala, persistent blackouts, and high inflation.

Who are ‘the rich’?

But to return to the salient issue: how do we define “the rich” who must pay more?

According to Sars, in the 2021 tax year, 82.1% of assessed individual taxpayers had taxable income below R500 000 (they fell below the tax return submission threshold). These taxpayers earned 48% of the total taxable income and contributed 27.7% to the tax assessed.

A further 17.9% of taxpayers earned taxable income above R500 000 and were liable for 72.3% of the tax assessed.

In the context of a country with only 15.9 million in employment (fourth quarter of 2022), are those who earn more than R500 000 “the rich”? Or, compared to the 29 million people getting by on social grants, perhaps those younger than 65 whose taxable income exceeds R91 250 a year (2023 tax threshold) could be regarded as “rich”.

No doubt, many would regard that threshold as too low, even with the level of inequality in South Africa.

If there were an agreed definition of the earnings band to be regarded as “middle class”, one could assume that anyone earning above the band would be “rich”. Of course, taxable income is not the only criteria when deciding who is among “the rich”. One needs to look at an individual’s total net worth.

From a purely taxable income perspective, however, some would regard it as “self-evident” that those who earn R1 million or more a year are definitely “the rich”.

There are 408 288 registered individuals with a taxable income of more than a R1m a year, according to National Treasury’s estimates for 2023/24 published in the Budget Review. These people, who constitute 5.7% of registered taxpayers whose taxable income exceeds the tax threshold, will pay 43.9% of PIT in 2023/24.

According to Tax Consulting SA, historically, Sars’s classification of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) is taxpayers whose gross income exceeds R7m a year, or whose gross wealth exceeds R75m. According to Sars, some 7 400 assessed individuals had a taxable income of more than R5m in 2021. (It did not provide a breakdown, by taxable income, of taxpayers beyond that figure.)

Perhaps this small group of HNWIs is what is meant by “the rich”. If so, most taxpayers can rest easy.

The point is that when proponents of a BIG (or any other permanent expenditure item) propose taxing “the rich” to fund it, the first question a taxpayer should ask is: what do you mean by “the rich”?

We may assume we know who they’re talking about. But in a country where the PIT burden falls on relatively few taxpayers, many “middle-income” South Africans, despite being burdened by debt and struggling to save for retirement and other things, should not be surprised if it turns out that “the rich” includes them.

The rich already pay more tax. As income goes up so does the tax rate on the tax table.

The article is inconclusive and at times quite puzzling.

Also the rich probably pay more VAT than the not so rich. They buy more.