The economy could be thrown into negative growth because of South Africa’s newly acquired grey-listing status. Grey-listing reduces a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth by between 0.5% and 1.5%, says Iraj Abedian (pictured), the chief executive of Pan-African Investment and Research Services.

Abedian says Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana will have to recalibrate all his 2023 Budget projections by at least 0.5%.

National Treasury has projected growth of 0.9% for the year, while the South African Reserve Bank has a far less optimistic view and estimates growth at 0.3%.

If the impact of grey-listing is taken into account, the country will be close to recession in a best-case scenario and in recession with a worst-case scenario on Treasury’s projections.

“This is very rough and ready. We still have to see what position the market will take, what the severity of the situation is, and how much government will rely on the banking sector to do some of the controls,” says Abedian.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has given the government until 2025 to address eight matters to show that South Africa has sufficient controls to combat money laundering and terrorism financing.

Current growth projections

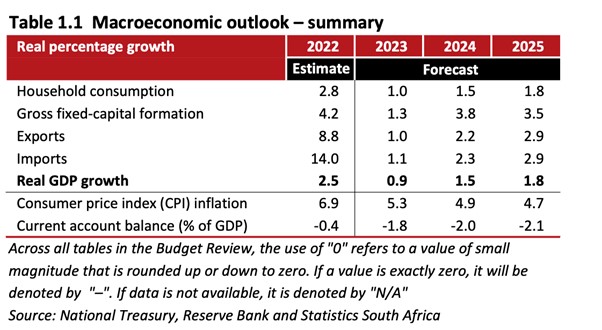

The minister projected growth of 0.9% this year, 1.5% next year and 1.8% in 2025, when South Africa must comply with the outstanding issues identified by the FATF.

In his 2023 Budget Review, Godongwana said Treasury was expecting revenue to grow by R351 billion to just more than R2 trillion by 2025/26. He expects gross tax revenue collections to increase by 5.6%, 6.7% and 7.1% over the next three years as economic growth “gradually improves”.

However, Godongwana acknowledged that higher revenue collections require “sustained investment and economic” growth. The downward recalibration must also include tax receipt projections, says Abedian.

The longer the country stays on the grey list, the more its economic growth will be eroded. “People will get used to the country being a money-laundering centre. We will then not attract foreign investors, but foreign crooks.”

Grey-listing’s impact on GDP growth figures could be worse if combined with other risks. If the government does not move fast enough to address the outstanding matters identified by the FATF, or if the country has to deal with another corporate collapse such as Steinhoff, or scandals such as the unresolved Phala Phala matter, the impact will be worse.

“Markets can take a view that things are not getting better, and that they are actually getting worse. When the market starts withdrawing capital […] Who knows how long is a piece of a string,” says Abedian.

No-go investment destination

South Africa has been in a declining foreign direct investment (FDI) position for a few years. Webber Wentzel said in its analysis of the impact of grey-listing that it will discourage FDI and reduce capital inflows. South Africa will be viewed as a high-risk jurisdiction for business, so some foreign investors might withdraw their investments.

“Some international financial institutions have policies that prevent them from doing business with grey-listed countries, or at least limit the scope of business that can be conducted. Such restrictions will further impede business and foreign investment,” the Webber Wentzel team said.

Abedian says international institutions that still want to invest in South Africa will have to jump through so many more hoops than what would have been the case in previous years. Presidential investment summits will be a challenge.

“Foreign investors will have to go through so many checkpoints to make sure that the person or company they are investing with are not involved in criminal activities such as money laundering or terrorism financing,” he says.

It is inevitable that investors will question whether it is worth their while to go through all the new compliance hurdles or to look for new markets.

Successful prosecutions

Godongwana said the country could be off the list by mid-2024. Abedian says countries can take anything from three to 10 years, depending on how quickly they move.

In essence it requires a mix of three things to get off the list:

- Appropriate legislation;

- Appropriate institutions to fight organised crime and money laundering; and

- Evidence (this is where the timing becomes important) that the legislation and institutions ensure arrests and successful prosecutions.

The government has amended several pieces of legislation, and the General Laws (Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Terrorism Financing) Amendment Act was signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the end of last year.

Godongwana has allocated R265 million to the Financial Intelligence Centre over three years to implement the recommendations of the State Capture Commission. However, it does not bode well for the country that people who have been identified and charged with criminal and corrupt activities are years later still not behind bars.

“That is what is going to take time. We will have to get enough successful prosecutions to show that our system works,” says Abedian.

Amanda Visser is a freelance journalist who specialises in tax and has written about trade law, competition law and regulatory issues.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies