Fears of extreme outcomes – regardless of the final result of US President Donald Trump’s tariff threats – are enough to drive market volatility, according to economic experts at Schroders.

Since Trump’s inauguration on 20 January, global markets have been navigating turbulent times. According to a timeline compiled by AP News, Trump used his inaugural address to declare his intention to “tariff and tax foreign countries to enrich our citizens”. On his first day in office, he announced plans to impose 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico on 1 February but did not immediately outline his approach to taxing Chinese imports.

On 1 February, he signed an executive order imposing tariffs on imports from Mexico, Canada, and China – 10% on all Chinese imports and 25% on those from Mexico and Canada, effective 4 February. Justifying his decision by declaring a national emergency over undocumented immigration and drug trafficking, Trump’s move sparked a swift backlash and threats of retaliation from all three countries.

Two days later, he agreed to a 30-day pause on the Mexico and Canada tariffs as both nations took steps to address US concerns over border security and drug trafficking. However, his 10% tariffs on all Chinese imports proceeded as planned on 4 February.

China responded immediately, imposing new duties on American goods and launching an anti-monopoly investigation into Google. Additional tariffs – including 15% on coal and liquefied natural gas and 10% on crude oil, agricultural machinery, and large-engine vehicles – were set to take effect on 10 February.

On 13 February, Trump unveiled a “reciprocal” tariff plan, vowing to match foreign countries’ import tax rates.

By 4 March, Trump’s 25% tariffs on Canadian and Mexican imports took effect, although Canadian energy exports were taxed at a reduced 10%. He also doubled tariffs on Chinese imports to 20%.

In response, Canada, Mexico, and China announced retaliatory measures. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged tariffs on more than $100 billion in US goods, while Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum signalled her country’s intention to impose countermeasures. China introduced tariffs of up to 15% on key US farm exports and expanded restrictions on American companies.

On 5 March, Trump granted a one-month exemption for US automakers, delaying tariffs on Mexican and Canadian imports at the request of Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis. The following day, he extended the exemption to many other Mexican imports and some from Canada but maintained plans to implement “reciprocal” tariffs on 2 April.

Tensions escalated further on 10 March, when China imposed additional 15% tariffs on major US agricultural exports, including chicken, pork, soybeans, and beef.

And it is likely that these tariff hikes won’t stop here as Trump sets his sights on natural resources.

On 10 January, he announced plans to raise tariffs on steel and aluminium, removing exemptions from his 2018 steel tariffs and ensuring that all steel imports are taxed at a minimum of 25%. He also increased aluminium tariffs from 10% to 25% (with these changes set to take effect on 12 March).

Then, on 25 February, he signed an executive order directing the Commerce Department to assess whether a tariff on imported copper is necessary to protect national security, citing its role in US defence, infrastructure, and emerging technologies.

Just days later, on 1 March, he signed another executive order instructing the Commerce Department to evaluate whether tariffs on lumber and timber are needed to safeguard national security, arguing that a strong domestic supply of wood products is essential for the construction industry and the military.

According to George Brown, senior US economist, and David Rees, head of global economics at Schroders, the market’s reaction underscores the difficulty investors face in assessing tariff policies. In February, for example, the US dollar fluctuated in response to tariff fears. Global shares fell on 3 February, while the dollar rose after news broke that the US planned to apply tariffs on goods from Mexico, Canada, and China on 4 February.

“Financial markets are not waiting to discover all the detail before pricing possible impacts, and this is leading to increased volatility across asset classes,” say Brown and Rees.

New tariffs could have triple the impact of 2018 trade war

During Trump’s first term in 2018, China was the main target of US tariffs. However, China managed to bypass many of these tariffs by re-routing goods through third-party countries, including Mexico.

“Obviously, re-routing goods would be much harder for Mexico and Canada given that the goods travel over land. What this means is that the impact of these tariffs, if levied, is likely to be greater this time around than in Trump’s first term,” say Brown and Rees.

The two experts note that the 2018 trade war with China had a minimal impact on inflation. Prices in the 11 tariff-affected categories rose by just 2.5%, adding only 0.1% to US core Consumer Price Index inflation.

“However, the announced tariffs on Canada and Mexico ought to have a more substantial impact, if implemented as strictly as initially suggested. One reason for this is that a much larger share of trade would be captured if Mexico and Canada were involved. These countries account for 28.3% of total US imports versus 13.6% for China.”

Sebastian Mullins, head of multi-asset and fixed income at Schroders Australia, adds that unlike the phased-in approach of the 2018 trade war, Trump’s latest tariffs – once implemented – are expected to affect $1.4 trillion worth of goods, making their impact three times larger.

The US imports most of its goods from China, Mexico, and Canada, but Canada and Mexico are also the largest buyers of US exports.

“This means not only do tariffs threaten higher inflation in the US but potentially lower growth, as their exports are curtailed by retaliatory tariffs,” says Mullins.

Bloomberg Economics estimates these tariffs could raise inflation by 0.7% while cutting 1.2% from GDP.

“The effects will still be one-sided, as Mexico and Canada export 35% and 22% of their respective GDPs to the US, whereas the US exports only 1.5% and 1.2% of its GDP to Canada and Mexico. So, in a war of attrition, the US will likely win. The question remains at what cost,” says Mullins.

What could this mean for the EU?

So far, no tariffs have been announced on the European Union. However, on 13 February, Trump indicated that other nations, including India and European countries, could face new tariffs of up to 25%.

According to Brown and Rees, EU companies also face the risk of China’s dumping products in Europe because of US tariffs on Chinese exports.

They predict that if discussions shift towards Europe, the EU will likely try to negotiate a deal before any tariffs take effect.

“Europe may seek to buy more weapons and LNG (liquefied natural gas) from the US. The EU runs external surpluses (exports more than it imports), and if it were to lose US demand due to tariffs, it would be difficult to replace that with demand from elsewhere.”

The market impact of tariffs: risks and nuances

Andrew Rymer, senior strategist at Schroders’ Strategic Research Unit, notes that several economies are at risk from tariffs, particularly those with which the US has a trade deficit. However, he points out that the economic and market impact is more nuanced.

“So far this year, the announced tariffs appear to have been milder than financial markets had anticipated. Against the backdrop of tariff rhetoric, global equities have advanced, including double-digit rallies in Europe and China, in US dollar terms, as at 19 February 2025.”

Despite this, Rymer warns that market volatility remains a concern because of the risks of further tariffs, tariff rate escalations, and potential retaliatory measures.

“Tariffs have the potential to disrupt supply chains for both US and international listed companies. For companies in targeted economies, these could also suffer reduced competitiveness or reduced market access.”

He explains that trade could be redirected away from the US, causing ripple effects for companies worldwide.

“The same could be argued for US companies if reciprocal measures are implemented. The ability of impacted companies to pass on the tariff impact to customers is a key factor. There may be some companies which are insulated from, or which can weather tariffs more than others.”

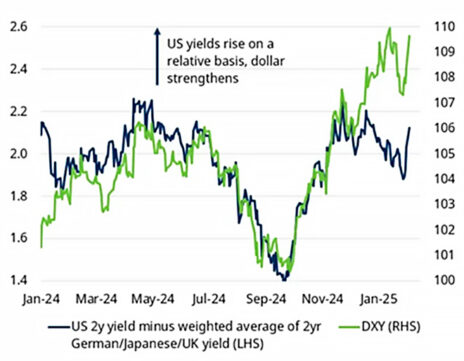

Rymer also highlights the impact of currency movements on investor returns. If the US dollar strengthens against local currencies because of tariffs, this could create a headwind for returns from partner markets in US dollar terms.

“The dollar is also relevant for US multinational companies with international revenues. It is worth bearing in mind that the S&P 500 revenue generation is only around 59% domestic. So, US companies earn over 40% of their revenues from non-US markets. In addition to any currency translation impact, these companies could also be subject to any retaliatory tariffs or measures.”

Ultimately, Rymer notes that predicting the effects of tariffs is complex, particularly given Trump’s unpredictable approach.

“Some economies may stand out as at greater threat of tariffs, but understanding the risks and differences between economies, markets, and individual company exposures remains crucial.”