For the first time, retirement annuity investors will be able to get early access to a portion of their retirement savings. Pieter Koekemoer, the head of Personal Investments at Coronation, says while it is great to have this option in the event of genuine financial hardship, investors need to understand the actual cost of early access.

South African investors with RAs have historically not been able to dip into their savings before retirement. Currently, these investors must wait until age 55 unless certain circumstances apply.

Once the two-pot retirement system comes into effect in September, RA investors will have early access through an annual withdrawal option. While the catalyst for allowing early access to one’s retirement savings was the economic hardship caused by the Covid lockdowns, utilising this option will be costly. It should ideally be reserved for periods of genuine financial hardship. We urge investors to ensure they understand the implications of early access, as we detail below.

RAs have technically already been a two-pot system

Investors retiring from their RAs have technically become accustomed to two separate pots in their retirement plans. This is because when you retire from your RA (at the age of 55 or later), you have the option to take one-third of your accumulated savings in cash (think of it as your lump-sum pot), while the remaining two-thirds must be used to buy a regular retirement income, such as a guaranteed or living annuity (your retirement income pot).

What changes for RA investors under the two-pot reform?

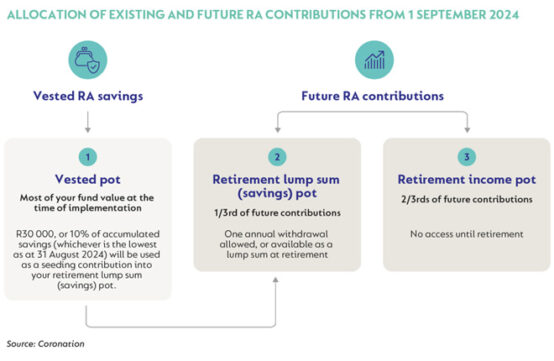

The two-pot system formalises the “split” in your retirement plan into separate pots by somewhat confusingly introducing three formal components into RA investors’ accounts:

- a vested pot (representing most of your RA fund value at the time of implementation);

- a retirement lump-sum pot; and

- a retirement income pot.

The most significant change under the new system is that you will be allowed one annual early withdrawal from your retirement lump-sum pot (or savings pot as it is called in the legislation). The value in your savings pot will initially be seeded by R30 000 or 10% of your fund value at implementation (whichever is the lowest), transferred from your vested pot. One-third of your future contributions (from 1 September) will also be allocated to this savings pot.

The following table shows the allocation of vested savings and future contributions from 1 September 2024.

An option but not an obligation

The significant change introduced by the two-pot system is that you will have the option, but not the obligation, to make one annual withdrawal from the entire balance in your savings pot.

It’s vital to understand that this new liquidity option comes with an important health warning. Early access is costly and can seriously reduce your standard of living in retirement. You are effectively borrowing money from your future self over a fixed term, and you will essentially lose the tax benefits you received from the government when you contributed towards your RA. Let’s unpack this a bit further.

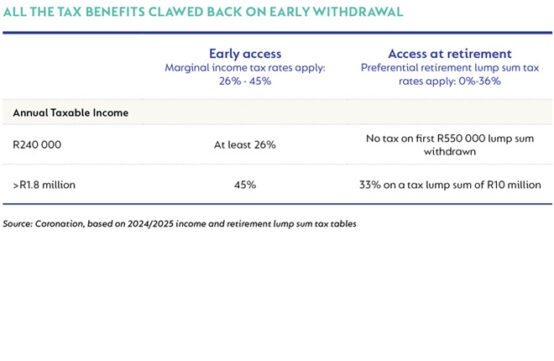

Exercising your access option is tax-disadvantaged

If you wait until retirement (any time after 55 for RA investors) before withdrawing your money, the preferential retirement lump-sum tax table will apply. But if you withdraw early, the more punitive marginal tax rates will be deducted from your withdrawal. This can significantly impact your retirement.

Let’s assume your annual taxable income is R240 000. Whatever withdrawal you make from your savings pot will be taxed at a rate of at least 26%, or more than a quarter of the money you access. This compares to zero tax on the first R550 000 lump-sum withdrawn at retirement age.

The principle also holds at the higher end of the income scale. With a R10-million lump-sum withdrawal at retirement, your effective tax rate will be 33% compared to the early withdrawal rate of 45%, assuming you earn more than R1.8m in that tax year. This is a 12-percentage point difference in the tax payable.

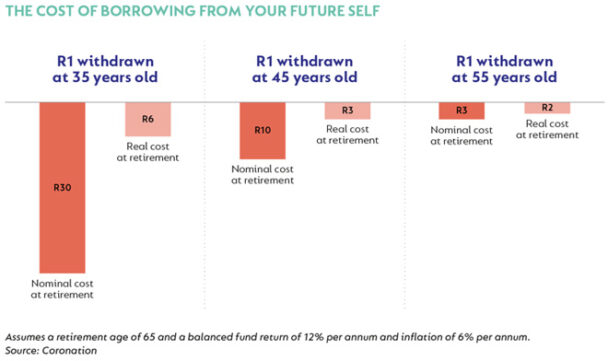

Early access is borrowing from your future self

Withdrawing early effectively means that you are borrowing from your future self over a fixed term at your expected rate of return on your RA investment.

To illustrate this, let’s assume you are 35 years old and intend to retire at age 65. Any R1 accessed through an early withdrawal may cost you R30 in lost retirement benefits at the time of retirement. In other words, by resisting the urge to access your savings early, your money could have multiplied by a factor of 30 over the three decades until retirement. While the numbers become less dramatic when you shorten the period between early access and retirement, they remain retirement-defining.

Even for individuals making an early withdrawal 10 years before their intended retirement date, it would still cost them R3 in lost retirement benefits for every R1 taken out early.

The bottom line

A single decade of missed compounding means you have effectively halved the purchasing power of the money taken out as part of your early withdrawal. The bottom line is that to avoid a significantly reduced standard of living in retirement, you must resist the temptation to make regular early withdrawals to fund discretionary spending today. By not accessing your retirement savings early, you allow the powerful effect of compound growth to work to your full advantage.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.

As a planner in the business for thirty five years, I place on record my utter disgust at the notion of even smelling one’s retirement money before the time, never mind having access to it!! I learned at an early age that if you made the maturity date 55 on an RA that’s when the money was taken. If you made it 65, that’s when the money was taken, even if it could be touched at 55. Its human nature. If its available, its gone.

This is nothing more than a plot to make South Africans even poorer and therefore more dependent on the government who ultimately want full control over the people and their money. Tell me I’m wrong.