Months before Donald Trump’s election last year, major banks and other market players doubted whether Trump’s second-term plans would lead to his aim to depreciate the US dollar.

Bloomberg reported in July last year that tariffs on the United States’ trade partners and others, and tax cuts that could lead to higher inflation and interest rates, could, in fact, push the US dollar higher. And they did initially. From winning the election in November last year to Trump’s inauguration in January this year, the greenback appreciated by more than 5% on a trade-weighted basis against advanced market currencies and by 3% against emerging market currencies.

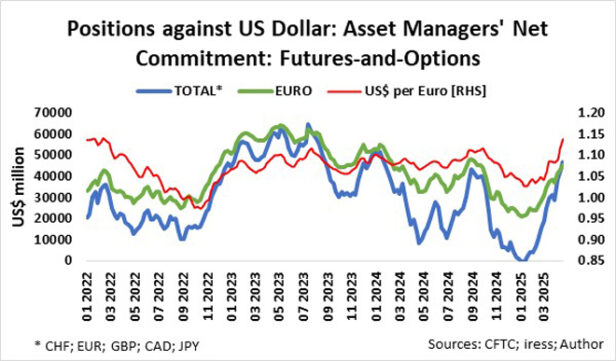

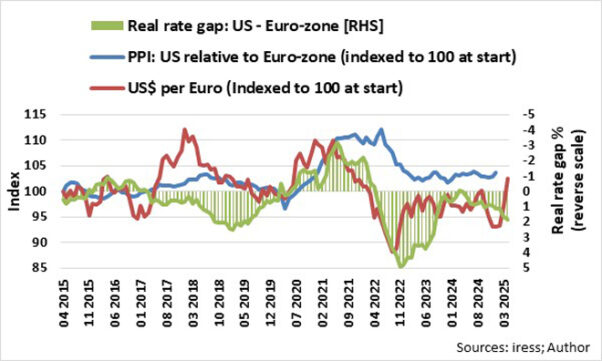

On a relative producer price index (PPI) basis (April 2015 = 100), the US dollar has been overvalued by about 6% since the start of 2023, and the surge until Trump’s inauguration took the overvaluation to more than 13%. According to CME statistics, US asset managers slashed their short positions against the US dollar by more than US$40 billion across major currencies (euro, Japanese yen, Canadian dollar, British pound, Swiss franc) from pre-election to inauguration day.

Inauguration day was a major inflection point because Trump announced the first bout of sweeping tariffs, which the market saw as an aggressive step to devalue the dollar. Further sweeping tariffs sent shockwaves through the global financial system, specifically through major sell-offs in US stocks and government bonds, which, on their own, have probably led to major capital outflows and significant pressure on the US dollar. Since inauguration day, US stocks (MSCI US$) have underperformed European stocks (MSCI MEUR$) by more than 16%, while the iShares 7–10-year US Treasury Bond ETF underperformed the iShares Euro Govt. Bond 7–10-year UCITS ETF by 8%.

In addition, US asset managers built fresh short positions against the US dollar of nearly US$50bn across major currencies, mainly in favour of the euro and the yen.

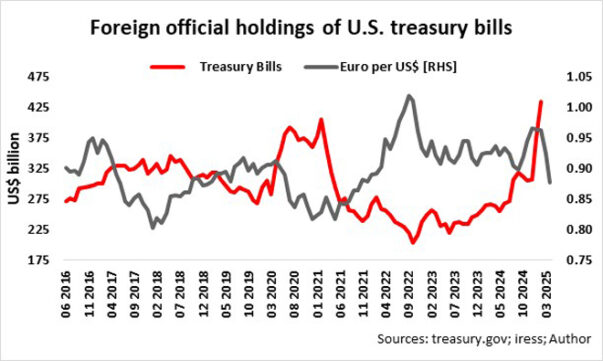

It is apparent that the amount invested in US treasury bills by foreign official institutions (central banks and others) is highly dependent on their views on the outlook for the US dollar. The sources of the funds could be anything from sales of longer-dated investment, including corporate bonds and even stocks. They reduce holdings in anticipation of the US dollar strengthening and, vice versa, increase holdings when US dollar weakness is anticipated. At this stage, the official treasury bill holdings are the highest on record, probably an indication of further US dollar weakness ahead.

Yes, sentiment towards the greenback is weak indeed!

Trump and his team have certainly achieved the first major objective of devaluating the US dollar. The 7% devaluation of the US dollar against the US trade-weighted advanced currency index took three months since he took office, whereas it took seven months during his first term. It is useful to note that from thereon it took another six months to bottom 3% lower.

In contrast, the US dollar has barely moved against the US trade-weighted emerging markets currency index since Trump’s inauguration in January. In comparison, the greenback devalued by nearly 5% in the first four months of his previous inauguration.

How low can the US dollar go?

With the European Union the US’s largest trading partner, I focus on the US dollar’s exchange rate to the euro.

The euro has gained about 10% against the US dollar since Trump took office, closing the gap with the relative PPI to about 3% but still in favour of the US dollar. From an economics point of view, Trump’s tariffs, together with the devaluation of the US dollar, are likely to be inflationary and will push the US PPI higher. In contrast, the strength of the euro is likely to be deflationary and even contribute to recessionary conditions in Europe.

The relatively higher PPI trajectory could therefore force the euro higher against the US dollar, but the relationship between the PPI and exchange rates is not always direct because there could be leads and lags due to other factors such as interest rate differentials adjusted for inflation, one of the major determinants in the valuation of currencies relative to each other.

The real interest rate gap, measured by the US real Federal funds rate (interest rate depository institutions charge each other for overnight loans of funds adjusted by the US consumer price inflation) minus the real EUR repo rate (interest rate at which the European Central Bank (ECB) lends money to banks adjusted by the EU consumer price inflation rate), widened to 1.9% in favour of the US after the recent cut in rates by the ECB. Against a backdrop of a weakening European economy, further rate cuts by the ECB will be brought forward and no action from the US Federal Reserve will see the real yield gap widen further in favour of the US and therefore the US dollar.

No wonder Trump is pushing the Fed to cut rates as soon as possible.

I remain somewhat bearish on the US dollar – more so against emerging market currencies and less against the euro because Trump will get his way. The reality, however, is that tariffs and tax cuts could soon thereafter lift the US dollar. Yes, what crisis?

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.