With the proposed two-percentage-point VAT hike scaled back to just 0.5 points in 2025/26 (and possibly another 0.5 in 2026/27), the expected R58-billion revenue boost it would have brought for 2025/26 has been slashed to R28bn. Something had to give – and that something appears to be social grants.

The postponement of the 19 February Budget Speech, triggered by fierce disagreements within the coalition government over raising VAT to 17%, sent shockwaves through political and economic circles. Now, as the dust settles, the question remains: who bears the brunt of this compromise?

The version of the Budget shared with journalists on the day showed that “Sources of Government Income in 2025/26” would be made up of taxes (R2 067.6bn), borrowing (R353.1bn) and non-tax value (R180.1bn). In total, that is R2 600.8bn. In Version 2.0 tabled on 12 March, the value derived from tax – now without the higher VAT percentage point increase – stands at R2 041.6bn. Borrowing is R370.4bn and non-tax revenue is R180.2bn. That is R2 592.2bn in total.

In other words, the government has R8.6bn less in the budget to plug all those many holes.

When comparing the two budget plans tabled this year, the most glaring difference is in “the main proposed spending additions over the medium term”. While the first sets aside R23.3bn to increase the value of social grants the second makes provision for only R8.2bn to increase the value of social grants. A difference of R15.1bn.

Could have, would have, should have

Social grants include child support, old-age, disability, foster care, care dependency, grant-in-aid, the Covid-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant, provincial social development, and support for women, youth, and persons with disabilities.

The number of social grant beneficiaries, excluding recipients of the SRD grant, is projected to increase from 19 million in 2025/26 to 19.3 million in 2027/28, driven mainly by a growing elderly population.

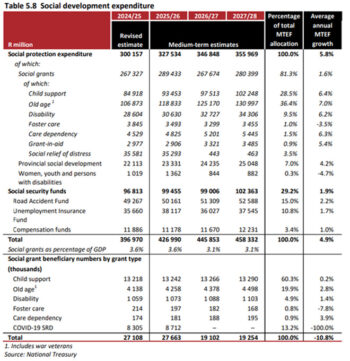

In Budget 2025 Version 1.0, the social development function was set to receive R427bn in 2025/26, rising to R458.3bn in 2027/28, with an average annual growth rate of 4.9%. Social grant spending would have accounted for 81.3% of this allocation. This would have represented an increase of R23.3bn over the medium term for 2025/26 compared to the previous year.

(Please note that numbers have been rounded up; refer to the tables for the exact amounts.)

The total amounts allocated for social grants under this version were:

- 4bn in 2025/26

- 7bn in 2026/27

- 4bn in 2027/28

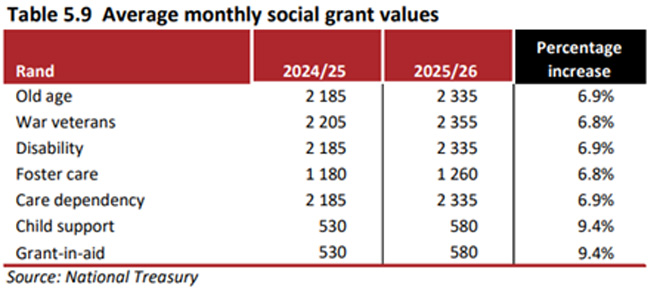

In April 2025, grant increases would have been as follows:

- Old-age, war veterans, disability, and care dependency grants: up by R150

- Foster-care grant: up by R80 to R1 260

- Child support and grant-in-aid: up by R50 to R580

Version 1.0

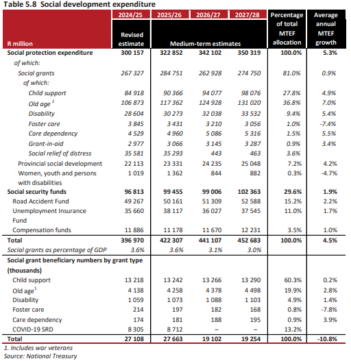

However, in Budget 2025 Version 2.0, the social development function is allocated a lower budget of R422.3bn in 2025/26, increasing to R452.7bn in 2027/28 at an average annual growth rate of 4.5%. Social grant spending makes up 81% of this allocation.

Under this revised version, the budget for social grants increases by only R8.2bn over the medium term compared to the previous year. The total amounts set aside for social grants are:

- 8bn in 2025/26

- 9bn in 2026/27

- 8bn in 2027/28

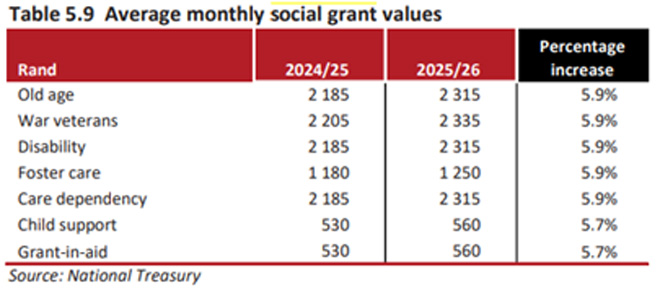

Grant increases in April 2025 under Version 2.0 are lower:

- Old-age, war veterans, disability, and care-dependency grants: up by R130

- Foster care grant: up by R70 to R1 250

- Child support and grant-in-aid: up by R30 to R560

Version 2.0

Despite these changes, one aspect remains unchanged: the SRD grant will be extended for another year until 31 March 2026. An amount of R35.2bn is allocated to continue the payment at R370 per month per beneficiary, including administration costs.

For grant recipients, this means they will receive R10 to R30 less per month than they would have under Version 1.0, depending on which grant they qualify for.

For the government, however, this adjustment results in significant savings, particularly in child support grants. By increasing the child support grant by only R30 instead of R50 as initially proposed, the medium-term estimates are revised downward:

- From R93.5bn to R90.4bn in 2025/26

- From R97.5bn to R94.1bn in 2026/27

- From R102.2bn to R98.1bn in 2027/28

Version 1.0

Version 2.0

Duncan Pieterse, director-general of the National Treasury, explains that social grants have always received inflation-related increases. However, he says with the cushion of a potential two-percentage-point VAT hike now off the table, the originally planned above-inflation increases are no longer feasible.

Home Affairs budget slashed

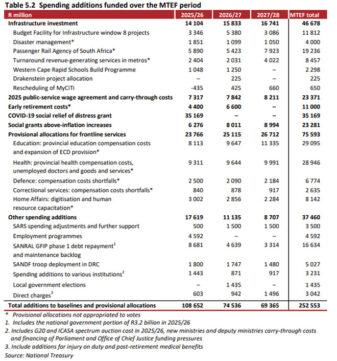

When comparing Version 1.0 to Version 2.0, the funds allocated for provisional frontline service delivery departments have been reduced from R75.6bn to R70.7bn, with Home Affairs: human digitisation and human resource capacitation taking the biggest hit.

In Version 1.0, funding for human digitisation and human resource capacitation over the next three years was set at R2.86bn (2025/26), R3bn (2026/27), and R2.28bn (2027/28). Under Version 2.0, these allocations have been reduced to R1.25bn (2025/26), R1.47bn (2026/27), and just R550 million (2027/28).

Version 1.0

Version 2.0

Human digitisation typically involves modernising records, services, and processes to improve efficiency, reduce paperwork, and enhance service delivery. This includes scanning and storing physical documents electronically, implementing digital ID systems, and using biometric verification for identity management.

Human resource capacitation focuses on strengthening the workforce through hiring, training, and skills development, ensuring staff can effectively handle growing administrative and digital transformation demands.

When comparing the numbers, it seems that the biggest impact is likely to be felt in border management, as available funding affects staffing and operational capacity.

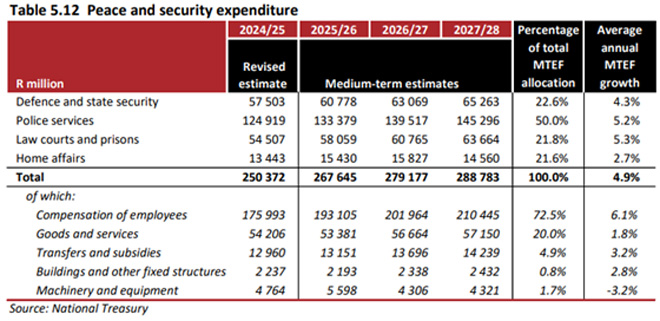

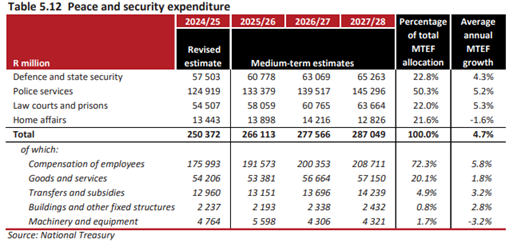

Under the Peace and Security expenditure – designed to promote safer communities, support business confidence, manage borders, and aid development – the only category with adjusted allocations between Version 1.0 and Version 2.0 is employee compensation.

- Version 1.0 allocated R193.1bn (2025/26), R202bn (2026/27), and R210.4bn (2027/28).

- Version 2.0 reduces these figures to R191.6bn (2025/26), R200.4bn (2026/27), and R208.7bn (2027/28).

Version 1.0

- Version 2.0

SARS gets an upgrade

Under Version 2.2, SARS received an additional R4bn, bringing its total allocation to R7.5bn over the next three years.

Speaking at a media briefing ahead of Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana’s Budget Speech on Wednesday, SARS Commissioner Edward Kieswetter explained that the increased funding would support a project aimed at reducing SARS’s debt book, which remains high because of uncollected taxes and returns not yet submitted.

In 2024/25, SARS used R1bn from the previous year’s allocation for a ring-fenced project to lower debt and speed up the processing of declarations and refunds. Encouraged by its success, SARS requested to retain this amount and secure an additional R1bn to expand debt-reduction efforts.

For 2025/26, R2bn is allocated to tackling outstanding returns and debt, followed by R1bn a year in the two subsequent years to sustain these efforts.

South Africa’s Budget: Starving the Poor to Feed the Fat Cats

South Africa’s latest budget is a gut punch to the poor and productive, a merciless squeeze on those already struggling to survive. Yet, the real outrage—the elephant in the room—remains untouched: a bloated, overpaid, underperforming cadre of government officials who suck up oxygen and resources while delivering little in return. These 1.2 million public servants, roughly 2% of the population, enjoy lavish salaries, inflation-proof pensions, and lifestyles guaranteed by the sweat of productive citizens. Meanwhile, 30-50% of South Africa’s children go to bed hungry, protein-deficient, and trapped in a cycle of poverty—all so these cadres can cruise in the latest SUVs and fill their trolleys with groceries.

The numbers tell a damning story. According to National Treasury, public-service compensation spending grew slower than nominal GDP until the mid-2000s. But since 2004, that trend flipped. Today, government wages gobble up 11% of GDP—a staggering 17% when you factor in the full scope of the public sector. Since 2006/07, average public-service remuneration has outpaced per capita GDP growth, ballooning to 4.7 times the average citizen’s income. This isn’t just a statistic; it’s a symptom of a system rigged against the taxpayer. More than 95% of public servants earn more than the bottom 50% of registered taxpayers, while remuneration for national and provincial government employees consistently outstrips private-sector wages.

A Global Embarrassment

South Africa’s public-sector pay isn’t just high—it’s obscene by international standards. A recent OECD study found that South African public-sector managers earn salaries comparable to their counterparts in Norway, a country with a GDP per capita nearly five times higher. Adjusted for US dollar purchasing power parity (PPP), top civil service managers rake in compensation equivalent to nine times South Africa’s GDP per capita—far above the OECD average of six. Even non-management senior officials, teachers, and education personnel enjoy some of the highest pay relative to GDP per capita globally. This isn’t merit-based prosperity; it’s a taxpayer-funded gravy train.

And who’s footing the bill? The productive citizens and businesses drowning under slow economic growth, high unemployment, and a shrinking tax base. A recent study pinpointed public-sector wage increases—not headcount growth—as the primary driver of government spending. In essence, South Africa is borrowing money, piling on debt, to sustain the lavish lifestyles of an incompetent elite while millions languish in poverty.

The Human Cost

The consequences are visceral. While cadres upgrade their cars and dine in comfort, child malnutrition festers. Between 30-50% of South African children suffer from hunger and protein deficiency—stunting their growth, their minds, and their futures. This isn’t just a budgetary issue; it’s a moral failure. Every rand funneled into an overpaid bureaucrat’s pension is a rand stolen from a child’s plate. The disconnect is stark: a tiny 2% of the population thrives, while the rest are left to scrape by.

A Broken System

How did we get here? Decades of cadre deployment and unchecked wage hikes have turned the public sector into a jobs-for-pals scheme, prioritizing loyalty over competence. Unlike the private sector, where salaries reflect market demand and performance, government pay scales seem to operate in a parallel universe—immune to economic reality. The result? A workforce that’s overcompensated, underproductive, and insulated from accountability.

Compare this to the private sector, where innovation and efficiency are survival traits. South Africa desperately needs a Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)—a lean, no-nonsense unit tasked with slashing waste and aligning public-sector salaries with reality. Better yet, let’s fast-track an AI-driven evaluation of skills and market-related pay scales. If a government employee’s job doesn’t justify their paycheck in the private market, why should taxpayers fund it?

A Path Forward

The solution starts with a hard freeze on government wages until they reach sustainable levels—say, 7-8% of GDP, in line with healthier economies. No more borrowing to bankroll incompetence. Pair that with a ruthless audit of performance: tie pay to results, not tenure or connections. And those gilded pensions? Scrap the final-salary guarantees and shift to defined-contribution plans, like the private sector has endured for years.

South Africa can’t afford to keep feeding the fat cats while starving its future. The productive class and the poor deserve better than a government that prioritizes its own over the people it claims to serve. It’s time to stop the bleeding, rethink the system, and put competence over cronyism. Anything less is a betrayal of the nation’s promise.