To make a real difference in clients’ lives, retirement benefit counselling (RBC) needs to start much earlier – ideally five to ten years before retirement – not at resignation or the three-month countdown currently mandated by law.

Kagisho Mahura, the chief executive of Gradidge Mahura Investments, brought this argument into focus at last month’s Institute of Retirement Funds Africa conference. Based on his firm’s experience since the Pension Funds Act (PFA) amendment made RBC compulsory for all retirement funds in March 2019, Mahura shared a stark reality: too often, clients face a harsh wake-up call when they realise – too late – that their retirement dreams are misaligned with their savings.

Starting counselling earlier, he argued, could prevent the distress and disappointment that many retirees face, giving them time to adjust and plan proactively for the retirement they envision.

“We’re asking the members of board of trustees to embrace the spirit of the law, not just the letter. We can’t just be complying. We’ve got to be a bit more compassionate towards our members. We’ve got to invest a bit more time in talking to them and discussing with them the things that cause them distress,” he said.

When more is less

Mahura shared some valuable insights gathered over seven years of counselling clients. Based on internal data, he explained that for most members, retirement capital forms the backbone of their financial security in retirement.

“When we sit with a member, and we’re looking at all the sources of income that they want to enjoy in retirement, 70% comes from the retirement capital itself,” he said.

He further noted that, for many, retirement savings represent the largest sum of wealth they have accumulated – sometimes even surpassing the value of their homes. This reality is critical to understand, he explained, because it “starts creating some mental issues”.

“We now start having a conundrum of problems,” Mahura added. “This leads to cognitive dissonance.”

Mahura said that in this scenario, cognitive dissonance refers to the mental stress that members suffer when the dreams they have do not match the reality they are facing.

It’s a familiar scenario: overestimating what your money can buy. Take, for instance, receiving a bonus of R10 000 and eagerly spending it on house repairs, a new wardrobe, or a special weekend away, only to realise a few months later that the total cost was far higher, possibly pushing you further into debt. Now, imagine the same scenario with a retirement payout of R1 million or more. What many envision they can do with such a large sum and what it actually affords are often worlds apart.

“This is one of the biggest problems that we find with members of retirement funds, because this is the greatest amount of money they’ve ever seen in their own lives. The dreams they have with their retirement capital are much greater than what they can actually achieve with it,” he said.

Where does the money go?

In counselling sessions, Mahura outlined a familiar narrative among retirees. When asked about their plans for retirement, clients share that the first thing they want to do is settle their debts.

“The greater problem is that they actually accumulate more debt towards retirement with the hope of using their retirement capital to settle their debt,” Mahura noted. “These are people who already don’t have enough to feed themselves on their retirement capital, but already they’re accumulating expectations.”

One of the most common desires, particularly among women, is improvements to their properties. “We’ve been in many homes as part of our counselling where the house has been extended, but there’s not enough money to put in the ceiling inside the house,” he said.

Mahura noted that men, on the other hand, often envision finally buying a luxury car. “That’s the first thing they’re going to do with their retirement capital.”

Mothers often allocate a significant portion of their retirement capital to support their children.

Mothers particularly of sons who have been trying to get married for years are going to lose their retirement capital to give them the best wedding that they’ve ever had.

He also mentioned a common phenomenon he describes as “upgrading the spouse”: leaving long-term partners for a new relationship.

“The problem is that nobody speaks to them about this,” Mahura said. “We see it, we see what happens two or three years later.”

Mahura said this is the point where retirement funds should engage with their members for a reality check.

Reality bites

A living annuity is an investment that requires annual withdrawals, also known as a drawdown.

The FSCA recommends the following drawdown rates for living annuities based on age:

- Age 60: recommended 4.5%, maximum 7.0%

- Age 65: recommended 5.0%, maximum 8.0%

- Age 70: recommended 5.0%, maximum 8.0%

- Age 75: recommended 5.5%, maximum 8.5%

In South Africa, the regulatory requirement for living annuity drawdown rates is between 2.5% and 17.5% a year. This requirement is intended to prevent the premature depletion of funds.

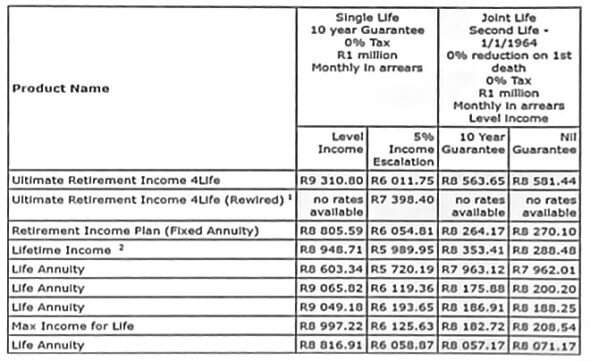

Mahura said penny drops for members when you tell them that for every R1 million, they will struggle to earn R7 000 a month if they buy a living annuity.

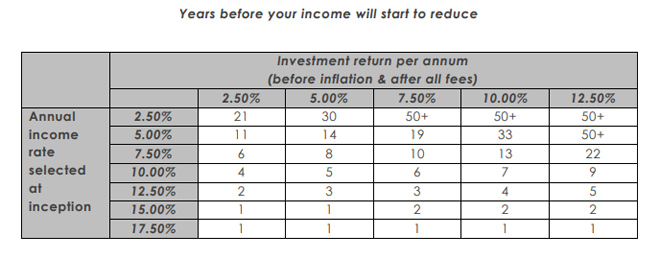

The ASISA Standard on Living Annuities (SLA) table (2010) shows the years before income will start to reduce based on the most recent income percentage selected by the client. The table assumes that the income drawdown rate is adjusted over time to maintain a real income by allowing for inflation.

Mahura explained that the table is designed to show members the point at which their income will start to diminish, given a specific rate of return and drawdown.

“When they start looking at these numbers, the reality starts to sink in. We draw some numbers for them and show them that whether you have R1m or R5m in capital, when you do a basic budget, many don’t come below R20 000 a month.”

He added that even with R5m in capital, achieving R20 000 in income may be difficult. “You’re not even going to meet the basic budget. And now you are retiring at R5m.

“If you are buying a life annuity, even at R5m, at a drawdown equivalent of about 8%, only then are you going to come close. But, of course, with a life annuity, you lose half of the benefit of leaving a legacy.”

When the penny drops

He noted that once this reality sets in, psychological strain takes hold, and members begin to realise that their financial integrity may be compromised.

“They used to be a stand-up person. They used to be a great father, a great mother. Now, they find themselves unable not only to provide for their own needs but also support their family. So psychologically, we are dealing with somebody who’s feeling less than. This is why I love the word counselling, because that’s where the real counselling starts to come in.”

The second part of the issue is the physical financial distress, where they lack enough money to buy food at the end of the month.

“And the greatest hurt is that realisation that the legacy they’ve dreamt of is not going to happen for their families.”

Finally, this leads to social distress and the disintegration of family relationships.

“As I said, some have left the first wife and started with the second wife, and now the sons are turning against the father and the mother, and then chaos starts to ensue, simply because somebody was not told in time what the reality of the retirement capital is.”

Transforming retirement counselling

Mahura advocated for repositioning RBC from a peripheral focus to a central element of strategic planning. He emphasised that waiting until three months before retirement to provide counselling is not good enough, because that’s where the distress happens.

“If we start earlier, we may not be able to give them enough capital to retire, but what we can do is give them enough strategies to start preparing themselves for that sorry outcome, which means they come up with the most ingenious ideas.”

He warned that if counselling is only offered at the last minute, members miss the opportunity to address their psychological stress and, more importantly, to develop strategies to secure their financial futures.

With all this in mind, he said there was a great need to expand RBC beyond the legal requirements, highlighting that it should encompass more than just risks, costs, and investment strategies.

First, he said, retirement funds needed to start communicating to the members in a language they understand.

“In other words, we can’t say we gave them a pamphlet or sent them to a call centre and consider our duty done. We need to communicate with them in a language they actually understand.”

He noted that with 11 official languages, it’s common for there to be no questions at the end of a presentation because attendees have not understood what was said, leaving them unsure about what to ask.

Additionally, he pointed out that the content of the information needs to change. He said members don’t know how to interpret benefit statements.

“You can’t say a member came and we gave them a benefit statement when they don’t even know the difference between an approved and an unapproved benefit. They don’t understand what the numbers mean. They lump everything together, leading to grandiose ideas about what they can do in retirement because they misread the benefit statement.”

In conclusion, Mahura called for a more inclusive and deliberate approach.

“Let’s remove the distress from our members. Let’s help them build legacies. We can do that by expanding the type of counselling we offer, enabling them to start building family wealth. If you give them half a chance to face the reality they will encounter at retirement, they will surprise you. We have seen it.”