The successful change to a new political dispensation in 1994 was a boon for South Africa because it paved “the way for the normalisation and expansion of the country’s international financial relations” (E.J. van der Merwe, SARB, March 1996). It heralded the end of the financial sanctions that starved the economy of foreign capital from the late seventies and led to the capitulation of the then apartheid government.

Fast forward to today. In my view, the results of the general election have put South African politics on a knife-edge, with realism on the one side and populism on the other. It is impossible to say how things will unfold over the next couple of weeks or months. With a government of national unity (GNU) on the cards, it does seem that the odds are increasing that realism and sanity will prevail, enabling the economy and the country to move on.

On the other side, however, a coalition leaning towards the confiscation of companies and land will undermine investor confidence in South Africa’s financial markets and cause huge capital outflows, while significantly higher borrowing costs offshore will be tantamount to imposing financial sanctions on the country, reversing all the progress made since 1994. Foreign investors voting with their feet could see exchange control restrictions imposed on non-residents and South African residents barred from investing offshore.

Comparing the 1994 and 2024 election periods

To get a feel of what may lie ahead in the coming weeks for South Africa’s financial markets, I compared the recent behaviour of the markets with their behaviour in the months before and after the watershed election of April 1994, after which former president Nelson Mandela formed a GNU in May that year.

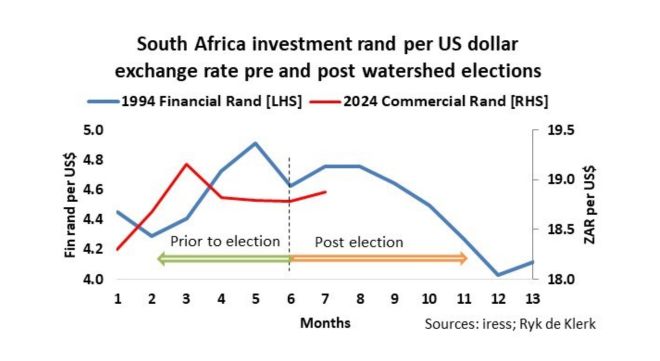

In 1994, South Africa still had the financial-rand mechanism. According to Wikipedia, “investments made in South Africa by non-residents could only be sold for financial rand, and limitations were placed on the convertibility of financial rand into foreign currencies” to restrict capital outflows. I simply called it the investment rand and compared its trend with the exchange rate of the rand to the US dollar (USDZAR) in 2024.

In 1994, the investment rand experienced a sell-off ahead of the election and strongly recovered days after the election, weakened slightly over the next two months as the market digested the formation of the GNU, and made a strong comeback, ending 15% higher against the greenback eight months after the election.

South Africa abolished the financial-rand mechanism in 1995.

This time, the rand was steady against the US dollar in the two months leading up to the election because of the BHP Group’s bid to acquire Anglo American Plc. The currency has weakened slightly after the election.

It seems that if the GNU manages to tick all the boxes with foreign and local investors, the rand exchange rate may follow a trend similar to the one it followed in the months after the 1994 election. Yes, considerable rand strength is in the offing through to the end of 2024.

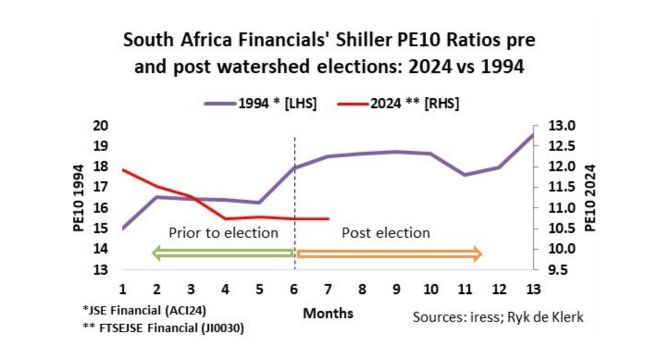

The ratings of South African financial shares as measured by Robert Shiller’s PE10 ratio (the price earnings ratio is based on average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years) were steady leading up to the 1994 election and jumped immediately after the election (yes, share prices rallied). The rally continued for another four months.

In 2024, the first three months of the year saw a sell-off in South African financial shares, but the ratings stabilised after BHP’s bid for Anglo American became known.

The 2024 election results have thus far had a negligible impact on the rating of the financial index, but gleaning from intraday trading patterns, it is evident that the investors are nervous. Financial shares are on very undemanding valuations, and any positive news, specifically a stronger rand, may catapult financial shares 15% to 20% higher in the coming months.

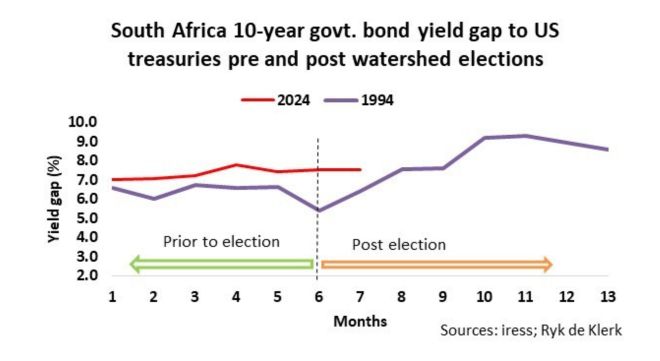

The yield gap between South African and US 10-year government bonds increased steadily to 7.5% from 7% since the end of last year. In comparison, the yield gap dipped immediately after the 1994 election but rose steadily afterwards with the re-establishment of South Africa as a borrower in the international capital markets (E.J. van der Merwe, SARB, March 1996).

A positive view on South African assets could see the yield gap between South African and US 10-year government bonds narrow by one hundred basis points to about 6.5% because of lower bond rates in South Africa.

In conclusion, the upside potential of South Africa-domiciled assets is starting to outweigh the downside potential, but the risks remain high.

This is why I have turned bullish on the rand, South African bonds, and the South African financial sector.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.

Good article Ryk. Enjoyed it. I agree there are some parallel ls between 1994 and 2024. However im less optimistic about large ZAR fx gains under a goid Gnu outcome but agree 100bp compression in yields are likely. FX front USDZAR will battle to break below 18.20s in absence of significant weaknesses in oil prices in my view.