Following the May election that resulted in the formation of a government of national unity (GNU), South African financial markets behaved in a fashion very similar to the way they did after the formation of a GNU in 1994.

The bellwether FTSE/JSE Financial Index, considered a leading indicator of the direction of the economy, tested its best levels in 18 months, rising by more than 19% since the announcement of a market-friendly GNU that ticks all the crucial boxes.

Long-dated South African government bonds represented by the JSE ASSA ALBI 12+ Years Bond Index rallied by more than 11% (clean price) as the yield to maturity dropped to a 16-month best of 11.45% from 12.85%.

The rand initially rallied to a 12-month high against the major currencies (5% against the US dollar and 6% against the euro) but weakened slightly afterwards.

But how sustainable are the rallies? How long will the “MoneyMoon” last?

While the tailwinds driven by newfound confidence in South Africa’s politics are likely to persist for some time, the country’s financial markets face increasing headwinds.

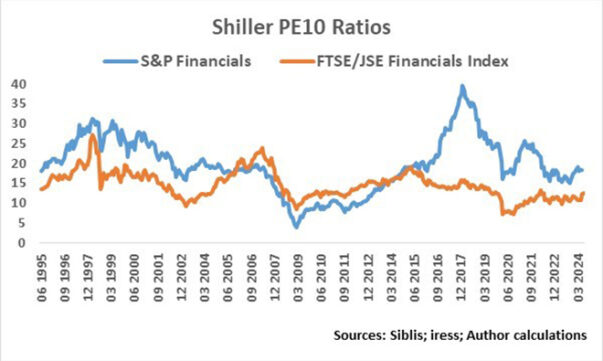

The South African financial sector’s valuation gap to the S&P Financial Sector, as measured by Robert Shiller’s PE10 metric, is about 50%, like the average discount in the 10 years following the 1994 election. From 2005, the gap closed, mainly because of strong sustainable economic growth, disciplined fiscal and monetary policies, and sovereign credit rating upgrades.

History is likely to repeat itself. It is unlikely that the valuation gap will close meaningfully over the next year or two. I think Coronation’s comments in the latest edition of its Corospondent last week say it all: “Longer-term reforms are being enacted; however, the pace thereof remains sedate, suggesting that higher growth is out of reach in the medium term. This still leaves South Africa in the perilous position of accumulating debt at an unsustainable pace.”

That means the future ratings of the South African financial sector are highly dependent on the ratings of global financial sectors, specifically the S&P financials.

A wall of worry lies ahead for US financial stocks, though.

The US economy is in the early stages of a recession.

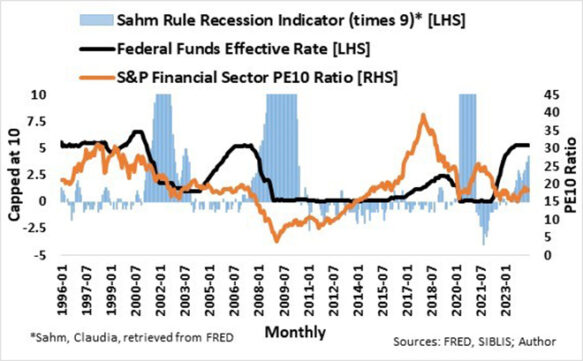

History has shown that when the Sahm Rule Recession Indicator, which is closely watched by the US Federal Reserve, reaches current levels, a US recession was under way.

The indicator, developed by Claudia Sahm, “signals the start of a recession when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate rises by 0.5 percentage points or more relative to the minimum of the three-month averages from the previous 12 months” (Federal Reserve).

As Bill Dudley, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist who served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from 2009 to 2018 and chair of the Bretton Woods Committee, said last week: “Although it might already be too late to fend off a recession by cutting rates, dawdling now unnecessarily increases the risk.”

Most analysts and others view cuts in the federal funds (fed funds) rate, the central interest rate in the US financial market, as bullish for the equity market. Historically, it was evident that initial cuts in the fed funds rate went hand in hand with deratings of US financial stocks as measured by the PE10 metric of the S&P Financial Sector. Why? The onset of a recession leads to the downscaling of company earnings forecasts, and stock prices adjust accordingly.

I do not think it will be different this time, particularly with the US presidential election later this year, which promises to be too close to call.

A US recession also does not auger well for the South African bond market, specifically for long-dated government bonds. The yield spread between SA 10-year government bonds and similar US bonds has narrowed to about 6.5%, the lowest since April 2019. Although there is an outside chance that the first-quarter 2018 low of 5.4% may be tested, history has it that the spread widens during the first two quarters of a US recession. Yes, we are probably at or near a low in the SA long-dated bond yield cycle.

When will foreign buyers close the door?

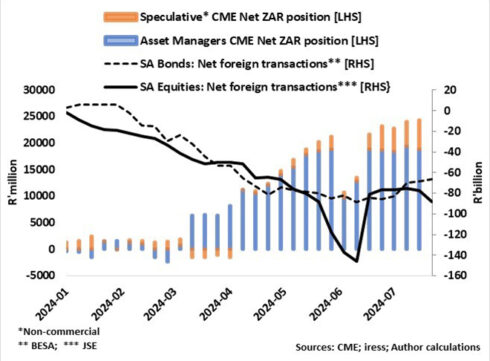

Foreigners have been net sellers of South African bonds – R88 billion for the calendar year until the GNU was announced – and turned net buyers of about R22bn since then. On the South African equities side, foreigners were steady sellers of about R88bn until a week before the election at the end of May. In the three weeks after the election, they dumped R57bn worth of stock but bought back R64bn worth the week thereafter.

In contrast to net sales of bonds and stocks by foreigners on the JSE, asset managers and speculators steadily opened and increased their net long positions on the rand to more than R21bn for the calendar year until the election through derivatives on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. They cut their positions by about R11bn in the week after the election but restored their long positions immediately after the GNU was announced.

Slower growth and recessions popping up all over the globe have sunk commodity prices. Being a commodity currency, the outlook for the rand is dimming.

The MoneyMoon after the elections is ending and storm clouds are gathering on global equity markets. This is why I have turned mildly bearish and opted for a defensive strategy.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.