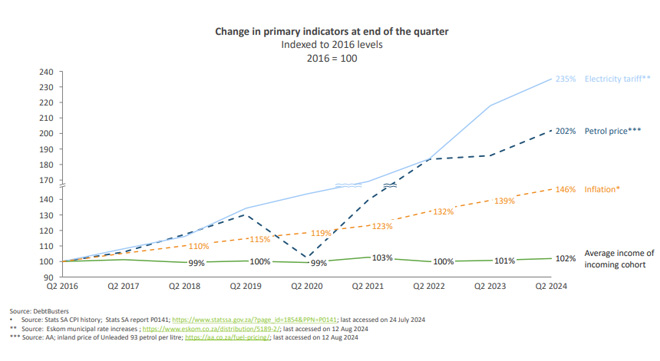

Feeling like your money isn’t stretching as far as it used to? You’re not alone. According to DebtBusters’ second-quarter Debt Index, despite inflation easing, consumers are taking home 44% less in real terms than they did in 2016.

The quarterly debt index analyses data from consumers who have applied for debt counselling through the debt management company. It found that compared to the same period in 2016, people who applied for debt counselling had significantly less purchasing power.

Despite a marginal 2% increase in nominal income since 2016, the cumulative impact of inflation, at 46%, has severely eroded purchasing power. In real terms, today’s income buys 44% less than it did eight years ago, leaving many consumers feeling the pinch.

Compared to previous quarters, overall debt levels have reduced. However, the burden of debt servicing has intensified, with these individuals now needing an average of 62% of their take-home pay to meet their debt obligations.

For those earning R35 000 a month or more, the situation is even more alarming, with 68% of their income going towards repaying debt.

Debt-to-income ratios have reached critical levels, particularly for top earners. Those with a take-home pay of more than R20 000 face a debt-to-income ratio of 128%, while for those earning R35 000 or more, the ratio soars to 167%.

For those who are wondering what that translates to, a debt-to-income ratio of 167% means that a person’s total debt is 167% of their income. For example, if someone earns R35 000 a month, they have debts amounting to R58 450 (R35 000 x 1.67).

This high ratio indicates that the person is carrying significantly more debt than their income might comfortably support, which can lead to financial strain. It suggests that for every R1 they earn, they owe R1.67 to creditors. This situation increases the risk of being unable to meet debt obligations, particularly if there’s a loss of income or unexpected expenses.

Secured vs unsecured debt

Secured debt is backed by collateral, such as a house or car, which the lender can seize if the borrower defaults. This typically results in lower interest rates.

Unsecured debt has no collateral, relying solely on the borrower’s creditworthiness, leading to higher interest rates because the lender carries increased risk. For the purposes of the index, unsecured debt refers to all debt other than vehicle finance and mortgage bonds. It includes credit card debt, overdraft facilities, personal loans, retail cards, store cards, and the like.

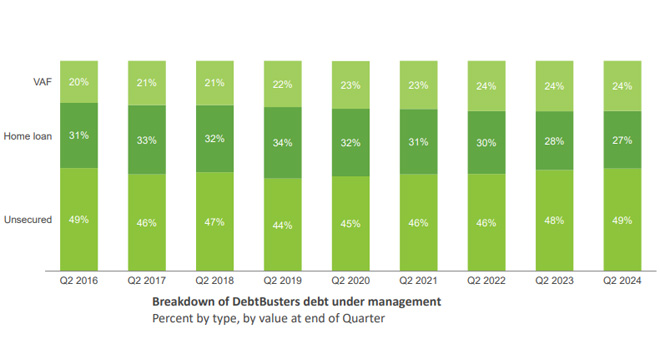

For the most part, the index shows that the nature of debt is mostly stable. Of the total debt book, home loans make up 27%, vehicle finance agreements 24%, and unsecured debt 49%.

The share of vehicle debt has increased in the past few years, indicating that more consumers with financed vehicles are seeking financial assistance. Unsecured debt contribution also appears to be increasing.

DebtBusters states that unsecured debt levels, particularly among high earners, are a cause for concern.

Although there has been a slight improvement in recent quarters, with unsecured debt levels 12% higher than in 2016, those taking home R35 000 or more have seen their unsecured debt levels rise by 38% over the past eight years.

DebtBusters state that, in the absence of meaningful salary increases, many consumers are relying on unsecured debt to supplement their income. The debt index found that consumers continue to use loans to make ends meet as inflation’s cumulative effect and persistently high interest rates erode their income.

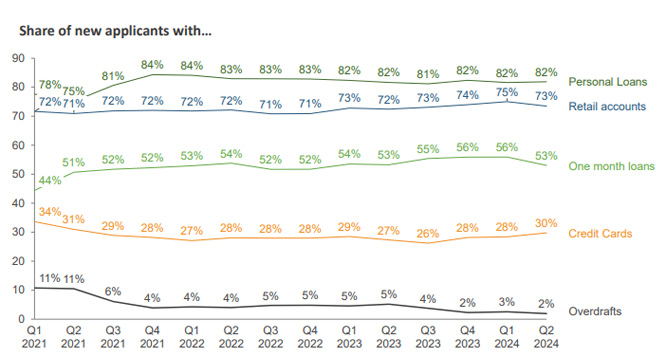

Looking more closely at unsecured debt, 82% of new applicants have a personal loan (at the time they apply for debt counselling); 53% have a one-month (payday) loan.

Personal loans refer to all other personal loans that have a repayment term of more than one month.

“These payday loans have become a lifeline for many households but are very expensive, with interest rates often in excess of 25% per annum,” DebtBusters states.

Indicators putting pressure on South Africans

Inflation has eased, but it remains at the upper end of the South African Reserve Bank’s target range and continues to constrain consumer finances.

Since 2016, electricity tariffs have increased by 2.35 times, the petrol price has doubled, and the compounded impact of inflation is 46% – all three indicators putting additional pressure on South Africans.

Although there are indications that interest rates may finally start to tick down, DebtBusters states they have been consistently high for more than a year.

“Although consumers are better able to deal with elevated but stable interest rates, they are still feeling the impact of the successive rate increases that started November 2021.”

Benay Sager, the executive head of DebtBusters, explains that when the interest rate increases began, people started to feel the increasing pressure of servicing asset-linked debt. The average interest rate for a bond went from 8.3% a year in the fourth quarter of 2020 to 12.3% in the second quarter of 2024.

“More alarmingly, the average interest rate for unsecured debt is now at an eight-year high of 26% per annum.”

Sager says it’s not all bad news. The median debt-to-annual-income ratio is stable and has been low for the past four quarters. Although still high at 105%, it is much lower than levels seen in the past few years.

“We welcome this, as well as the fact that debt counselling enquiries are up by 18% and registrations for online debt-management tools have increased. It indicates more people are taking action to deal with debt.”